Inverted U wave, a specific electrocardiographic sign of cardiac ischemia

References

- Ori M. Biology and poisoning by spiders. In: Tu A, editor. Handbook of natural toxins, vol 2. New York7 M. Dekker Inc; 1984. p. 396.

- Ellenhorn MJ, Barcelous DG, editors. Medical toxicology. New York7 Elsevier; 1988. p. 1112.

- Wong RC, Hughes SE, Voorhes JJ. Spider bites. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:99 - 105.

- Maretic Z. Lactrodectism: variation of clinical manifestations pro- voked by Lactrodectus species of spiders. Toxicon 1983;21:457 - 66.

- Muller GJ. Black and brown spider bites in South Africa. A series of 45 cases. S Afr Med J 1993;83:399 - 405.

- de Haro L, David JM, Jouglard J. Latrodectism in southern France. Presse Med 1994;23:1121 - 4.

- Rauber A. Black widow spider bites. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1983; 21:473 - 85.

- Maguire JH, Spielman A. Arthropods bites and stings. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. New York7 McGraw Hill Inc; 1998. p. 2551.

- Russel FE. Toxic effects of animals. In: Klaasen CD, editor. Casarett and Doull’s toxicology. New York7 McGraw Hill; 1996. p. 801.

- Clark RF, Wethern-Kestner S, Vance MV, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment of black widow envenomation. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:782 - 6.

- Moss HS, Binder LS. A retrospective review of black widow spider envenomation. Ann Emerg Med 1987;16:188 - 91.

- Gueron M, Ilia R, Margulis G. Arthropod poisons and the cardiovascular system. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:708 - 14.

- Dzelalija B, Medic A. Latrodectus bites in northern Dalmatia, Croatia: clinical, laboratory, epidemiological, and therapeutical aspects. Croat Med J 2003;44:135 - 8.

- Pulignano G, Del Sindaco D, Giovannini M, et al. Myocardial damage after spider bite (Latrodectus tredecimguttatus) in a 16-year-old patient. G Ital Cardiol 1998;28:1149 - 56.

- Pneumatikos IA, Galiatsou E, Goe D, et al. Acute fatal toxic myocarditis after black widow spider envenomation. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:158.

Inverted U wave, a specific electrocardiographic sign of cardiac ischemia

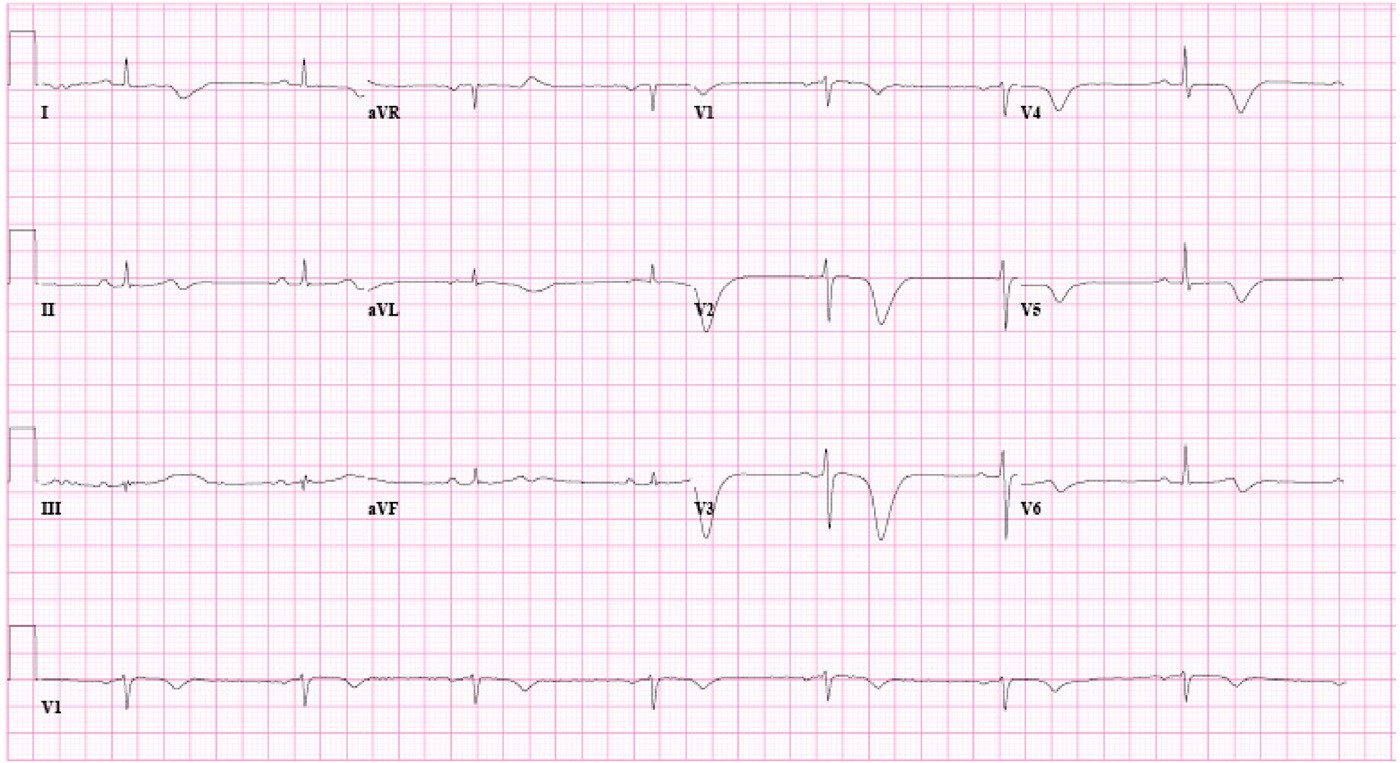

A 55-year-old woman with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department with a complaint of chest pain. She had similar chest pains in the past, and a cardiac catheterization 2 years ago showed significant coronary stenosis. At that time, a stent placement was recommended, but she refused. She did not take any medication on a regular basis. She had retrosternal chest pain on exertion in the past 2 years, but it became significantly worse in the 3 days before presentation, being precipitated even with minimum exertion and associated with shortness of breath and nausea. Over the same 3-day period, she took 8 to 10 tablets of aspirin 325 mg per day. The latest episode of chest pain occurred about 2 hours before presentation. Upon presentation, her pulse rate was 85/min, blood pressure 158/85 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18/min, and temperature 36.28C with oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. Her physical examination was unremarkable. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) (Fig. 1) showed normal sinus rhythm with inverted T waves in the lateral precordial leads and negative U waves in V2 and V3. Her complete blood count and basic metabolic panel were within normal limits. Her cardiac biomarkers were the following: creatine kinase (CK), 48 IU/L; CK-MB, 1.4 ng/ mL; troponin I, 0.1 ng/mL (normal b0.04 ng/mL); C-reactive protein (CRP), 3.4 mg/L; and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), 95 pg/mL. She was treated for unstable angina with heparin, metoprolol, aspirin, and simvastatin,

Fig. 1 Inverted T waves in V1 to V4 and inverted U waves in V2 and V3.

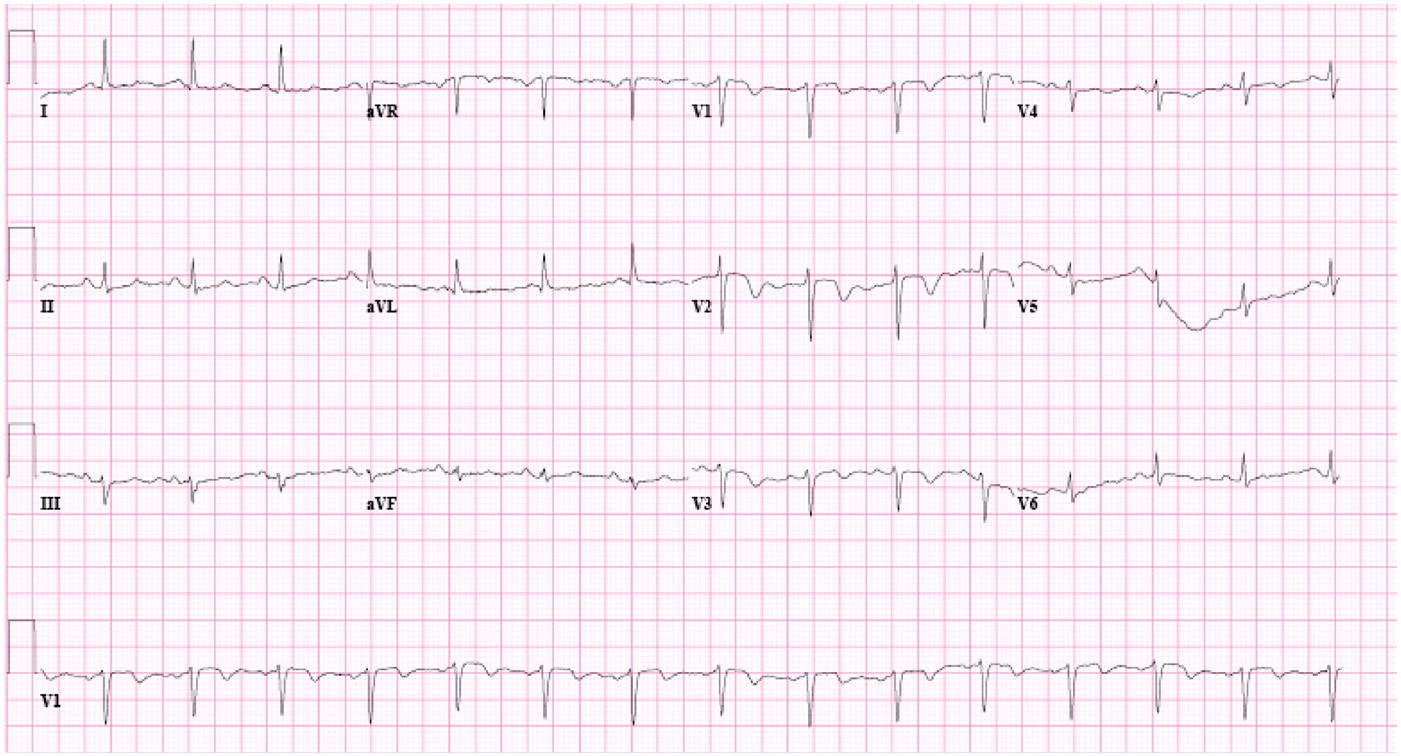

Fig. 2 The third ECG of the patient showing increased depth of the T inversion in the lateral precordial leads and a new inversion of T waves in the inferior leads.

and serial cardiac enzymes and ECGs were taken. A second ECG about 2 hours after the first showed a significant increase in the depth of the inverted T waves and resolution of the negative U waves. A second set of cardiac enzymes showed CK of 43 IU/L, CK-MB of 1.7 ng/mL, and troponin I of 0.14 of ng/mL. A third ECG (Fig. 2) at this time was very similar to the second ECG in having deep inverted T waves in the lateral precordial leads, although it also showed new inverted T waves in the inferior leads. The patient underwent a cardiac catheterization that showed 25% stenosis of the distal left main coronary artery, more than 90% stenosis of the proximal and mid left anterior descending (LAD) artery, and about 65% stenosis of the right coronary artery. With a staged intervention approach, 3 stents were placed in the LAD artery, and the next day, 3 stents were placed in the right coronary artery.

Inverted or negative U waves may be the only sign, and a very specific sign, of ischemia on ECG [1-3]. Negative U waves are defined as a negative deflection as small as

0.5 mV from the TP baseline [4]. In distinguishing a negative U wave, the possibility of terminal T wave inversion should be ruled out by determining the QT interval in those leads that do not show the negative U waves. The amplitude of the U wave is inversely related to the heart rate, and therefore, it is more easily recognized on ECG in a bradycardic state. Although a positive U wave carries favorable prognosis in patients with myocardial infarction [5], a negative U wave is associated with

significant coronary artery disease (CAD) stenosis, usually in the LAD artery [1-3], and also with hypertension [6,7], valvular diseases, and congestive heart failure [8,9]. The association of negative U waves and stroke seems to be dependent on the presence of CAD [10]. Negative U waves are a transient electrocardiographic finding and may not be found in subsequent ECGs or in a stress test [1]. Negative U waves may be the only ECG sign of ischemia, or they can be associated with other ECG signs of ischemia, for example, with inverted T waves, as in our patient. Reinig et al [4] recently showed that negative concordance of T and U waves has the poorest prognosis and is most specific for ischemia. In their study, the ECGs were divided to 3 groups: negative T-U concordance (both T and U waves negative); type 1 T-U discordance (negative T waves and positive U waves); and type 2 T-U discordance (positive T waves and negative U waves). Patients with negative T-U concordance had a statistically significantly (P value b .0001) higher rate of CAD (88% vs 58%) in their cardiac catheterizations and also higher rates of hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy compared with patients with T-U discordance [4]. These results indicate that, not only are T wave inversion and U wave inversion separately signs of ischemia but also the specificity increases significantly when both are inverted on ECG. The association of negative U waves with LAD artery and left main coronary artery disease points toward their prognostic value.

Inverted U waves may be a singular and specific sign of ischemia. Their diagnostic specificity increases when asso- ciated with inverted T waves. Inverted U waves have prognostic value, and their occurrence calls for immediate attention with further workup to investigate CAD.

Ali A. Sovari MD Farhad Farokhi DO Abraham G. Kocheril MD

Department of Internal Medicine

University of Illinois Urbana, IL 61802, USA

E-mail address: alizadeh@uiuc.edu doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2006.11.004

References

- Gregory SA, Akutsu Y, Perstein TS, et al. Inverted U waves. Am J Med 2006;119(9):746 - 7.

- Gerson MC, McHenry PL. Resting U wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Am J Med 1980;69:545 - 50.

- Correale E, Battista R, Ricciardiello V, Martone A. The negative U wave: a pathogenetic enigma but a useful, often overlooked bedside diagnostic and prognostic clue in ischemic heart disease. Clin Cardiol 2004;27(12):674 - 7.

- Reinig MG, Harizi R, Spodick DH. Electrocardiographic T- and U-wave discordance. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2005;10(1): 41 - 6.

- Sparrow D, Weiss ST, Thomas Jr HE, Rosner B, Baden L. The relationship of the U wave to the 10-year incidence of myocardial infarction. Am J Epidemiol 1983;117(6):729 - 34.

- Georgopoulos AJ, Proudfit WL, Page IH. Relationship between arterial pressure and negative U waves in electrocardiograms. Circulation 1961;23:675 - 80.

- Bellet S, Bettinger JC, Gottlieb H, Kemp RL, Surawicz B. Prognostic significance of negative U waves in the electrocardiogram in hypertension. Circulation 1957;15(1):98 - 101.

- Kanemoto N, Imaoka C, Suzuki Y. Significance of U wave polarities in previous anterior myocardial infarction. J Electrocardiol 1991; 24(2):169 - 75.

- Gurlek A, Oral D, Pamir G, Akyol T. Significance of resting U wave polarity in patients with atherosclerotic heart disease. J Electrocardiol 1994;27(2):157 - 61.

- Doagn A, Tunc E, Ozturk M, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in patients with ischaemic stroke and their prognostic importance. 1. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58(5):436 - 40.

Misleadingly migratory pain in acute renal infarction

Acute renal infarction is an uncommon disease. Patients usually complain of acute unilateral flank pain, low back pain, and abdominal pain with or without hematuria. Because of unspecific symptoms and rarity, detection of renal infarct is often delayed or misdiagnosed as nephrolithiasis, pyelone- phritis, acute gastroenterolitis, and unspecific abdominal pain. Herein, we report a patient with acute right renal

infarction secondary to abdominal aortic thrombosis with right renal artery involvement, who presented with mislead- ingly migratory pain of acute appendicitis.

A 59-year-old male with alcoholism history presented to the emergency department (ED) with epigastric pain for several hours. The patient stated the pain began suddenly with the onset of nausea, vomiting, and anorexia shortly thereafter. The pain was described as a constant, aching, and radiating to back. It was without exacerbating or relieving factors. There was no history of trauma, fever, chills, diarrhea, hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, dysuria, hematuria, or change in bowel habits. Vital signs were a temperature of 378C (98.68F), pulse rate of 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 17 breaths per minute, and blood pressure of 160/87 mm Hg. Physical examination was unremarkable, except for localized epigastric tenderness, without rebound or muscle rigidity. Alcoholic pancreatitis was initially suspected, and some laboratory tests were done. Laboratory tests showed white cell count of

7600/lL, with 90% segmented neutrophils. His biochemical

profiles including renal function and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), coagulation function, lipase, and cardiac enzymes were all normal. Urinalysis showed no red blood cells or white blood cells and was otherwise negative. An electrocar- diogram showed normal sinus rhythm. There were no remarkable findings on chest radiography or abdominal plain film. An ultrasound showed neither stones nor signs of obstructive uropathy.

Two hours later, he complained of right lower quadrant pain. There was moderate tenderness at McBurncy’s point and minimal tenderness of the epigastrium. There was voluntary guarding at the point of maximal tenderness but no rebound. Psoas muscle sign was positive, and Rosvign sign was negative. Neither costovertebral angle tenderness nor knock- ing pain was noted. A tentative diagnosis of acute appendicitis was made, and a contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography was obtained. It revealed a normal appendix but did show abdominal aortic thrombosis with right renal artery involvement and a large hypodense, 5 x 3 x 7 area in the right kidney without enhancement after contrast injection (Fig. 1). An echocardiogram showed no thrombus, a normal left atrium, and normal left ventricular size with normal ejection fraction. He was treated with heparin and subsequent warfarin and was discharged with preserved renal function.

Renal infarction is a very uncommon disease and easily misdiagnosed. This leads to delay in initiation of treatment and significant morbidity. In a necropsy study, Hoxie et al [1] reported an incidence of 1.4%, but only a few of these cases were suspected antemortem. Since acute renal infarction is rarely detected in clinical practice, the real incidence is pro- bably underestimated. The causes of renal infarction include thromboembolism; artheroembolic, thrombotic, and traumat- ic vessel anomalies; coagulopathy, and idiopathic reason.

Clinical presentation is variable and usually one of sudden onset flank, low back, or abdominal pain with or without hematuria. The characteristic pain is usually acute onset, severe and sharp with or without radiating pain. Atypical