Sex differences in STEMI activation for patients presenting to the ED 1939

a b s t r a c t

Objective: The objective was to determine whether sex was independently associated with door to ST-elevation myocardial infarction activation time. We hypothesized that women are more likely to experience lon- ger delays to STEMI activation than men.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults >=18 years who underwent STEMI activation at 3 urban emergency departments between 2010 and 2014. The Wilcoxon rank sum test and logistic regression were used to compare men and women regarding time to activation and proportion with times b15 minutes, respectively.

Results: Of 400 eligible patients, we excluded 61 (15%) with prehospital activations, 44 (11%) arrests, and 3 (1%) transfers. Of the remaining 292 patients, mean age was 61 +- 13 years, 64% were men, 57% were black, and 37% arrived by ambulance. Median door to STEMI activation time was 7.0 minutes longer for women than for men (25.5 vs 18.5 minutes, P = .028). In addition, men were more likely than women to have a door to STEMI activa- tion time b15 minutes (45% vs 28%, P = .006). After adjusting for race, hospital site, Emergency Severity Index triage level, Arrival mode, and chief concern of chest pain, the odds of men having STEMI activation times b15 mi- nutes were 1.9 times more likely than women.

Conclusions: Women have longer median door to STEMI activation times than men. A significantly lower propor- tion of women (28% vs 45%) are treated per American Heart Association guidelines of door to STEMI activation b15 minutes when compared with men, adjusting for confounders. Further investigation may identify possible etiology of bias and potential areas for intervention.

(C) 2016

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the largest cause of mortality for women in the United States. Although the implementation of the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines has reduced risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality for ST-elevation myocardial infarction by

? This research was funded through a FOCUS Medical Student Fellowship in Women’s Health supported by the Edna G. Kynett Memorial Foundation.

?? Poster presented at Society of Academic Emergency Medicine, San Diego, CA, on May 13, 2015.

?? KC and AMM conceived the study and designed the trial. KC obtained research

funding. KC, AMM, and FSS supervised the conduct of the trial and data collection. FSS pro- vided statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data. KC drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. KC and AMM take responsibility for the paper as a whole.

* Corresponding author at: Department of Emergency Medicine, Ground Floor, Ravdin Bldg, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA, 19104-4283. Tel.: +1 215 662 2386, +1 215 260 6594 (Mobile); fax: +1 215 662 3953.

E-mail address: [email protected] (A.M. Mills).URL: http://www.twitter.com/@AngelaMMills (A.M. Mills).

24% since 1999 [1], a sex gap still remains with excess mortality in women with STEMI [2]. Women hospitalized for acute myocardial infarc- tion receive less aggressive medical and invasive treatments, partially owing to their older age, less extensive atherosclerosis, and delayed and atypical presentations [2]. For those who do receive percutaneous coro- nary intervention (PCI), door to balloon times have improved in the past decade, but differences between men and women still persist-for both thrombolytics and PCI-with longer door to needle or balloon times for women after adjusting for all other baseline characteristics [3,4]. Prior studies have not formally examined the association between sex and delay to STEMI activation but rather have examined time to bal- loon or thrombolytic intervention as a primary outcome. The focus of this study is to examine time from door to STEMI activation. This inter- mediate interval is a more relevant measure in an emergency setting and could be modifiable by emergency department (ED) intervention. An Australian prospective study found significant delays for females compared with males for door to balloon times as well as its compo- nents including door to STEMI activation time, whereas no such study

has been reported in the United States [5].

The purpose of our study was to determine if a patient’s sex was in- dependently associated with a longer door to STEMI activation time. A

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.082

0735-6757/(C) 2016

Patient demographics by sex

Characteristic Women

(n = 106a)

Men

(n = 186a)

P value

arrest, or transfer from another hospital were excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Measurements

n % n %

|

Age (y +- SD) |

62.9 +- 12.5 |

60.3 +- 13.7 |

.1 |

|||

|

Race |

Black/Afr Am |

74 |

70% |

91 |

51% |

.004 |

|

White |

25 |

24% |

66 |

37% |

||

|

Other race |

6 |

6% |

23 |

13% |

||

|

ESI level |

1 |

12 |

11% |

33 |

18% |

.29 |

|

2 |

71 |

67% |

110 |

59% |

||

|

3 |

23 |

22% |

42 |

23% |

||

|

Arrival by ambulance |

37 |

35% |

71 |

38% |

0.62 |

|

|

Chief concern chest pain |

76 |

72% |

145 |

78% |

0.26 |

|

|

Hospital |

Tertiary |

61 |

35% |

114 |

65% |

.09 |

|

Community 1 |

12 |

27% |

33 |

73% |

||

|

Community 2 |

33 |

46% |

39 |

54% |

||

a May not add up to totals because of missing values.

secondary objective was to compare the proportion of patients with door to STEMI activation time less than 15 minutes, in accordance with AHA Guideline recommendations. We hypothesized that women were more likely to experience longer delays to STEMI activation than men.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective cohort study of adults who underwent STEMI alert activation at 3 urban EDs within 1 health system with a total annual ED census of approximately 137 000 visits. The three EDs included a large tertiary care ED with an annual census of about 65 000 visits and a 4-year emergency medicine residency, and 2 communi- ty EDs with annual visits of 38 000 and 34 000, respectively. All 3 sites were PCI-capable hospitals with cardiac catheterization facilities avail- able 24/7 and used a shared electronic medical record (EMR). There were approximately 72 attending physicians at the 3 EDs who evaluated the study patients. The Institutional Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects at the XXXX approved the study.

Study population

Adult patients, 18 years and older, who presented between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014, and underwent STEMI alert activation from the ED were eligible for inclusion in the study. These patients were identified by a cardiology-managed database of all STEMI alert activa- tions initiated by emergency physicians. These events were recorded at the time of event, with manual entry of time stamps. STEMI alerts were initiated based on clinical presentation and electrocardiographic findings by the treating attending emergency physician. The full ED record was then linked by medical record number and encounter identifier from a shared EMR used in all 3 hospital ED sites (EMTRAC, Philadelphia, PA). ECG dates and timestamps were gathered by manual review of the electronic ECG database. After linkage, all records were deidentified. Patients with prehospital STEMI activation (haste), cardiac

The ED EMR was queried for patient demographics (sex, age, race/ ethnicity), chief concern, time of ED arrival, mode of arrival, and Emer- gency Severity Index (ESI) triage level (1-5; 1 = urgent, 5 = nonur- gent). Chief concern was defined as chest pain or other. Mode of arrival was defined as ambulance or other means of transportation. Diagnostic ECG was defined as the last ECG performed before activation time. Cardiology from each of the 3 sites provided time of STEMI alert activation for all patients. Door to STEMI activation time was defined as the time from initial ED arrival time to the time of STEMI alert activation.

There were multiple independent reviews of the data set to verify qual- ity and accuracy. Outliers with respect to door to STEMI alert activation time delays N100 minutes were reviewed manually to verify the time.

The primary outcome of the study was door to STEMI activation time. The secondary outcome was the proportion of patients with door to STEMI activation times less than 15 minutes, in accordance with AHA guidelines.

2.4. Data analysis

To compare men to women with regard to demographics and visit characteristics, ?2 or Fisher exact test was used for categorical data, and 2-sample t test was used for continuous variables such as age. Wilcoxon rank sum and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine differences between sex and sex/race groups, respectively, regarding median time to first ECG, diagnostic ECG, and STEMI activation. Fisher exact test was used to compare the men to women with regard to the proportion of patients with door to STEMI activation time less than 15 minutes.

Lastly, logistic regression analysis, modeled on STEMI activation time less than 15 minutes, was performed adjusting for age, sex, race, ESI triage level, arrival mode, chief concern and hospital site. All analy- ses were performed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Of 400 eligible patients, we excluded 61 (15%) with prehospital acti- vations, 44 (11%) arrests, and 3 (1%) transfers. A similar proportion of men (28%, n = 65) and women (24%, n = 43) were excluded (P =

.49). Men were more likely to be hasted prehospital activations (17% vs 11%, P = .15), and women were more likely to have arrest (15% vs 8%, P = .03). Of the 292 patients included for analysis, the mean age was 61 +- 13 years, 186 (64%) were male, 165(57%) were black/ African American, and 108 (37%) arrived by ambulance.

There were no significant differences between men and women with regard to age, ESI triage level, chief concern of chest pain, arrival mode, or hospital site (Table 1). Women were more likely to be black/ African American than men (70% vs 51%, P = .004). There were demo- graphic variations according to race and sex across the 3 sites; commu- nity hospital 1 had a higher proportion of white patients (71%,

Sex/race demographics by hospital site

Women (n = 106)a Men (n = 186)a

Hospital

|

Total |

Black/ Afr Am |

White |

Other race |

Total |

Black/ Afr Am |

White |

Other race |

|||

|

Tertiary (n = 172) |

61 (35%) |

41(67%) |

15 (25%) |

5 (8%) |

111 (65%) |

57 (51%) |

34 (31%) |

20 (18%) |

||

|

Community 1 (n = 45) |

12 (27%) |

4 (33%) |

7 (58%) |

1 (8%) |

33 (73%) |

5 (15%) |

25 (76%) |

3 (9%) |

||

|

Community 2 (n = 68) |

32 (47%) |

29 (91%) |

3 (9%) |

0 (0%) |

36 (53%) |

29 (81%) |

7 (19%) |

0 (0%) |

a Numbers may not total to n due to missing race. Tertiary Hospital had missing race for 3 men; Community Hospital 2 had missing race for 1 woman and 3 men.

ECG protocol by sex

Women

(n = 106)a

Men

(n = 186)a

P

value

minutes in men were 1.9 times the odds for women (P = .028, 95% con-

fidence interval: 1.1-3.4, Fig. 4).

Discussion

First ECG 7.6 (n = 103) 4.0 (n = 184) .015

|

Median door to (min) Diagnostic ECG |

14.8 |

(n = 103) |

9.2 |

(n = 184) |

.054 |

|

No. of ECGs received 1 |

61 |

58% |

119 |

64% |

|

|

before activation 2 |

32 |

30% |

55 |

30% |

.210 |

|

3-5 |

13 |

12% |

12 |

6% |

a May not add up to totals due to missing values.

compared with 28% and 15%), and in particular white male patients (76%, compared with 31% and 19%), who underwent activation com- pared with the tertiary hospital and community hospital 2. These find- ings reflected the patient demographics of the hospitals as a whole (Table 2). For all patients, median door to STEMI activation time was

20.5 minutes.

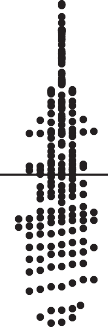

Men had significantly shorter median times from door to first ECG than women (4.0 vs 7.6 minutes, respectively; P = .015), but no differ- ence was seen for median door to diagnostic ECG time (P = .054) or the number of ECGs received before activation occurred (P = .210, Table 3). Median door to STEMI activation time was 7.0 minutes longer for women than for men (25.5 vs 18.5 minutes, P = .028, Fig. 1) and dif- fered by hospital site, with shortest times seen at community hospital 1 whose median time for women and men fell below 15 minutes (median = 12.3 minutes, interquartile range = 11.8-53.0 for women; median = 8.7 minutes, interquartile range = 5.5-18.8 for men). Median times for women and men were 26.8 and 18.5 minutes for the tertiary hospital and 30.0 and 30.6 minutes for community hospital 2 (Fig. 2). white men compared with women of any race and men of other races had significantly lower median STEMI activation times (10.8 vs 23-27

minutes respectively, P = .0002, Fig. 3).

Men were also more likely than women to have a door to STEMI ac- tivation time less than 15 minutes (45% vs 28%, P = .006). After adjusting for race, hospital site, ESI level, arrival mode, and chief concern of chest pain, the odds of a door to STEMI activation time less than 15

Prior studies have demonstrated a greater mortality rate for women (especially younger women [6,7]) with STEMI and longer door to bal- loon times in women undergoing PCI, thought to be in part due to incor- rect diagnosis and delays in treatment. Women with MIs are significantly less likely to report chest pain or discomfort on presenta- tion compared with men [8,9] and, furthermore, less likely to be re- ferred for [10] and receive Therapeutic procedures [11]. This study was conducted to assess whether there is a sex difference in door to STEMI activation time. We demonstrated that the median door to STEMI acti- vation time is significantly longer for women who present to the ED. Race was also noted to affect median time by its interaction with sex; white men had the shortest median time to activation as a distinct group from nonwhite men, whereas race was not a factor in median time for women. Median time was further observed to significantly vary by ED hospital site in accordance with the hospital’s patient demo- graphics and proportion of white men.

One prior study that directly measured the sex differences of the

time interval from door to activation was a prospective study conducted in Australia across 2 PCI-capable Tertiary care centers. They found that median times were 6 minutes longer for women (P = .012) [5], but their study did not account for race, and only patients who underwent Primary PCI were included. Although their similar findings corroborate our results, their study was as such not generalizable to our population. A study by Jackson et al [3] similarly found a sex-based difference in the interval from door to initial ECG, an immediate precursor to recognition of potential STEMI. They found that women had a 7-minute delay compared with men, adjusting for age, hospital, shift, triage level, race, and mode of arrival [3]. Although they looked only at the subset of patients whose initial ECG was diagnostic (excluding those requiring 2 or more ECGs), they also noted separately a significant delay to a subsequent ECG for women com- pared with men. Thus, together, their findings are similar to our study that included all patients who ultimately received an activation of STEMI alert

Fig. 1. Median door to STEMI activation by sex.

Fig. 2. Median door to STEMI activation by hospital site.

by physician regardless of the number of ECGs. The primary outcome of the study concerned the interval from door to thrombolytic therapy, which they also found was longer for women compared with men and also differed between the 2 hospital sites.

Our study included all ECGs from door to activation, and we found a significant difference between men and women in the time from door to first ECG that did not persist to a difference in door to diagnostic ECG and found no significant difference in the number of ECGs required

before activation occurred. The initial door to first ECG delay is notable, and although likely not a full explanation of the significant difference in activation time that is ultimately seen, further investigation may identi- fy potential bias and other factors that underlie both delays. Interven- tions may be required at many levels to improve outcomes as reflected by the prognostically meaningful “door-to-balloon” time. Although factors of bias may persist, further understanding of the differences in Disease progression and severity between men and

Fig. 3. Median door to STEMI activation time by sex/race.

Fig. 4. Adjusted odds of b15 minutes door to STEMI activation time.

women may illuminate areas of opportunity to better identify STEMI among women.

There werea number of limitations in our study. The patients included in the study are from PCI-capable, urban EDs in a single health system and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. However, the 3 sites did differ with respect to academic vs community setting, patient de- mographics, and presence of a training program. Secondly, we may have missed including patients with STEMI who were not initially considered by the emergency physician to have STEMI, which could underestimate the door to activation time. Because women often do not have a classic presentation, this could also underestimate the actual time for women. Thirdly, as this was a retrospective study, there may be some inaccuracies with the data including missing data and timestamps which were collect- ed in the process of patient care. However, this would likely be random and unlikely to differ between men and women.

Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated that women have significantly longer median door to STEMI activation times than men and that a signif- icantly lower proportion of women are treated per AHA guidelines of door to STEMI activation when compared with men, after controlling for po- tential confounders. More than 2 decades from the implementation of guidelines for STEMI management, continued efforts are still required to achieve guideline consistency for all patient populations. Further study may identify possible etiology of bias and potential areas for intervention.

References

- Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, Canto JG, Ornato JP, Gibson CM, et al. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST eleva- tion and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of myo- cardial infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J 2008;156(6):1026-34. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.030.

- Zhang Z, Fang J, Gillespie C, Wang G, Hong Y, Yoon PW. Age-specific gender differ- ences in in-hospital mortality by type of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2012;109(8):1097-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.12.001.

- Jackson R, Anderson W, Peacock 4th WF, Vaught L, Carley RS, Wilson AG. Effect of a pa- tient’s sex on the timing of thrombolytic therapy. Ann Emerg Med 1996;27(1):8-15.

- Kaul P, Armstrong PW, Sookram S, Leung BK, Brass N, Welsh RC. temporal trends in pa- tient and treatment delay among men and women presenting with ST-elevation myocar- dial infarction. Am Heart J 2011;161(1):91-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2010.09.016.

- Dreyer RP, Beltrame JF, Tavella R, Air T, Hoffman B, Pati PK, et al. Evaluation of gender differences in Door-to-balloon time in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Lung Circ 2013;22(10):861-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2013.03.078.

- Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1999;341(4):217-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199907223410401.

- Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Yarzebski J, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Sex differences in 2- year mortality after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2001;134(3):173. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-134-3-200102060-00007.

- Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, Bonow RO, Sopko G, Pepine CJ, Long T. Symp- tom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med 2007;167(22):2405-13.

- Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V, et al. Associa- tion of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA 2012;307(8):3223-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.199.

- Steingart RM, Packer M, Hamm P, Coglianese ME, Gersh B, Geltman EM, et al. Sex differ- ences in the management of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1991;325:226-30.

- Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1991;325(4):221-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199107253250401.