Variability in emergency department electronic medical record default opioid quantities: A national survey

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

American Journal of Emergency Medicine

journal homepage:

Variability in emergency department electronic medical record default opioid quantities: A national survey

Variability in emergency department electronic medical record default opioid quantities: A national survey

While opioid prescribing for acute pain in U.S. emergency departments (EDs) is more consistent with recommendations for a 3-day or less supply than in other settings, the average number of tablets prescribed still remains highly variable [1-3]. Further- more, larger initial prescriptions are associated with prolonged opi- oid use and potential for misuse [2,3]. Setting default tablet order amounts lower than the baseline average (e.g. 10 tablets) reduces the tablet number prescribed [4]. Conversely, if set too high (e.g. 20 tablets), prescribers are nudged into prescribing more than they would have without a default [5]. It is unknown whether EDs have default orders for opioid amounts and whether these defaults are consistent with the recommended 3-day supply (typically <=12 tablets) [6]. Thus, we conducted a national survey of U.S. EDs to determine the presence and size of default opioid tablet amounts. We surveyed the American College of Emergency Physicians

Table 1

Emergency department (ED) default opioid tablet order quantities by location of ED and presence of state policy limiting prescribing.

|

Category |

N |

% |

No Default N % |

Default <=12 tabs N % |

Default >12 tabs N % |

p-value |

|||||

|

All |

299 |

138 46.2 |

68 22.7 |

93 31.1 |

|||||||

|

US census region |

0.014 |

||||||||||

|

Northeast |

57 |

19.1 |

25 |

43.9 |

22 |

38.6 |

10 |

17.5 |

|||

|

New England |

16 |

8 |

50.0 |

3 |

18.8 |

5 |

31.3 |

||||

|

Mid-Atlantic |

41 |

17 |

41.5 |

19 |

46.3 |

5 |

12.2 |

||||

|

Midwest |

79 |

26.5 |

41 |

51.9 |

10 |

12.7 |

28 |

35.4 |

|||

|

E-N Central |

54 |

32 |

59.3 |

4 |

7.4 |

18 |

33.3 |

||||

|

W-N Central |

25 |

9 |

36.0 |

6 |

24.0 |

10 |

40.0 |

||||

|

South |

84 |

28.2 |

34 |

40.5 |

21 |

25.0 |

29 |

34.5 |

|||

|

South Atlantic |

47 |

17 |

36.2 |

12 |

25.5 |

18 |

38.3 |

||||

|

E-S Central |

11 |

4 |

36.4 |

4 |

36.4 |

3 |

27.3 |

||||

|

W-S Central |

26 |

13 |

50.0 |

5 |

19.2 |

8 |

30.8 |

||||

West 78 26.2 38 48.7 15 19.2 25 32.1

Mountain 25 11 44.0 5 20.0 9 36.0

Pacific 53 27 50.9 10 18.9 16 30.2

State legislation 0.023

Emergency Medicine Practice Research Network (EMPRN), a volun- teer national survey panel of 893 emergency physicians nation-

Limits opioid prescribing

109 36.6 42 38.5 34 31.2 33 30.3

wide. Outcomes included 1) the default number of tablets for the two most commonly prescribed opioids, hydrocodone/ac- etaminophen (5-325 mg and oxycodone/acetaminophen (5- 325 mg), 2) whether the ED had a default tablet number for each and 3) whether these defaults were for <=12 tablets. Additional data collected included: the ZIP code of respondents' ED mapped to U.S. state and whether a law was enacted at the time limiting Opioid prescription amounts according to data obtained from the National Conference of State Legislatures. Chi-square tests were used to determine differences in having an opioid default or tablet number within guidelines between US region and state laws.

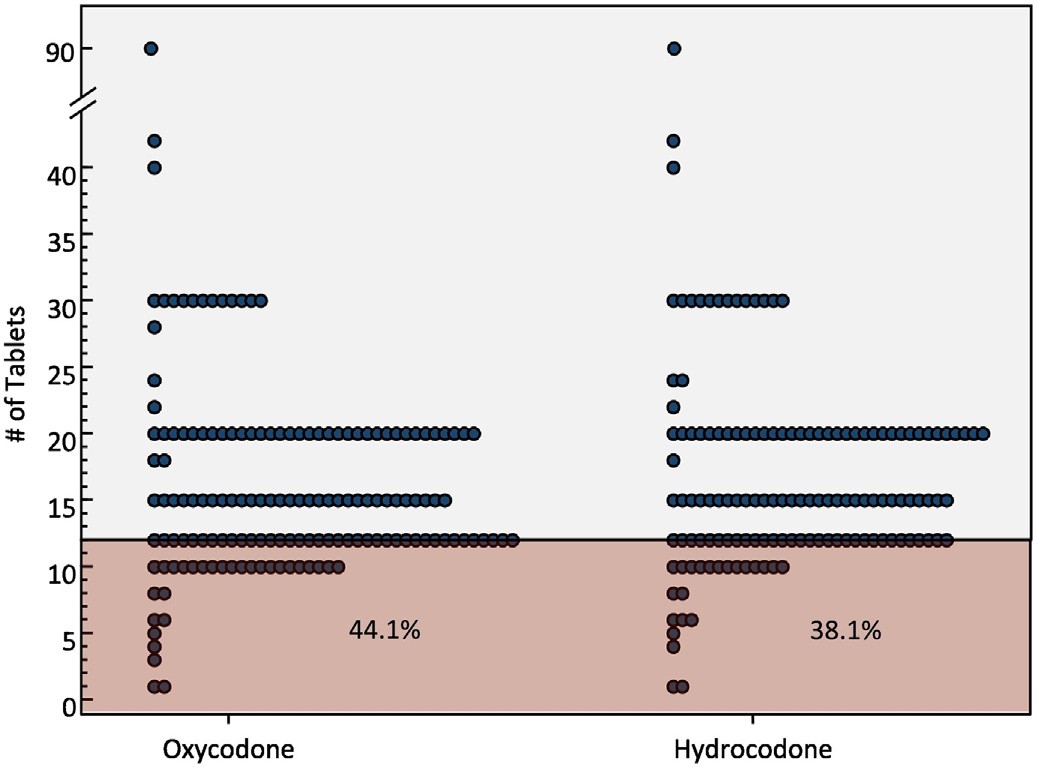

Of the 893 members surveyed, 299 (33%) from 47 states responded (Table 1). Defaults were present in 161 (54%) EDs. There was significant variation in default tablet amounts (Fig. 1). The median default tablet number for both hydrocodone and oxy- codone was 15 (IQR 12-20) with 22.3% and 25.0% being for <=12 tablets, respectively. Of EDs with defaults, 15 (10%) reported >=30 tabs (range 30-90 tablets). Northeast region EDs had the largest proportion of defaults for <=12 tablets (38.6%) versus no default (43.9%) or >12 tablets (17.5%, p = 0.014). EDs with default quanti- ties <12 tablets were more likely to be located in states with pre- scribing limits (50%) compared with those with no default (30%) or a default of >12 tablets (36%) (p = 0.023).

This study demonstrated wide variation in default opioid orders (from 1 to 90 tablets) with 42% having defaults >12 tablets among those with default quantities. Given the tendency for prescribers to use default opioid amounts, it appears that a significant proportion of existing EMR defaults may actually encourage higher prescrib- ing than if these EDs had no defaults or if the defaults were lower. We found that guideline concordant EMR defaults were more com- mon in states with opioid prescribing limits, suggesting that state

No limits 189 63.4 96 50.8 34 18.0 59 31.2

policies may encourage compliance. This study is limited by a sub- optimal response rate and limited data describing the characteris- tics of EDs. As a result, it is unclear whether these findings are representative of EDs nationally. In summary, our findings indicate that there is significant opportunity to change ED EMR opioid defaults to be concordant with existing national and state guidelines.

Fig. 1. Distribution of emergency department default opioid tablet order quantities among survey respondents and proportion for a standard 3-day supply (12 tablets) or less.

0735-6757/(C) 2019

None.

Erik J. Blutinger, MD, MSc

Delgado MK, Shofer FS, Patel MS, et al. Association between electronic medical record implementation of default opioid prescription quantities and prescribing behavior in two emergency departments. J Gen Intern Med 2018:1-3.

Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of

Pennsylvania, United States of America Corresponding author at: Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, United

States of America.

E-mail address: [email protected]

Frances S. Shofer, PhD Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of

Pennsylvania, United States of America Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Informatics, Perelman

School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, United States of America

Zachary Meisel, MD, MS Frances S. Shofer, MD, MPH, MSHP

Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, University of

Pennsylvania, United States of America Penn Injury Science Center, University of Pennsylvania, United States of

America Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Jeanmarie Perrone, MD Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of

Pennsylvania, United States of America Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Eden Engel-Rebitzer Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of

Pennsylvania, United States of America

M. Kit Delgado, MD, MS Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emer- gency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylva-

nia, United States of America Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Informatics, Perelman

School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, United States of America Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, University of

Pennsylvania, United States of America Penn Injury Science Center, University of Pennsylvania, United States of

America Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania,

United States of America

3 March 2019

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.03.023

References

- Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, et al. Opioid prescribing in a cross section of US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66(3):253-259.E1. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.026.

- Delgado MK, Huang Y, Meisel Z, et al. National variation in opioid prescribing and risk of prolonged use for opioid-naive patients treated in the emergency Department for Ankle sprains. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72(4):389-400. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.06.003.

- Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med 2017;376(7):663-73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1610524.

doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2017.10.33798.

Cheng D, Majlesi N. Emergency department opioid prescribing guidelines for the treatment of non-cancer related pain, https://www.aaem.org/UserFiles/file/ Emergency-Department-Opoid-Prescribing-Guidelines.pdf, ; 2013.

Frequency of emergency medicine resident dosing miscalculations treating pediatric patients

Frequency of emergency medicine resident dosing miscalculations treating pediatric patientsWe conducted a review of 500 consecutive IV orders placed by emergency medicine [EM] residents during the calendar year 2018 in the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Department of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Medical Center in New York City. We are located in an urban setting with an approximate census of 20,000 pediatric patient visits/year. We sponsor an active 3-year EM residency pro- gram during which residents [n = 50] work clinical shifts in the pediatric ER under the direct supervision of board-certified pedi- atric emergency medicine attending physicians.

EM residents ordered a variety of IV medications [ketorolac, morphine sulfate, various antibiotics, famotidine, etomidate, ondansetron, metoclopramide, various steroid preparations, seda- tive medications, magnesium sulfate, diphenhydramine, ketamine, acyclovir, insulin, glucagon, lorazepam, D25W, IV fluids with potassium chloride supplement]. Calculations identified deviation from recommended dosing [1] of >10% with 105 orders [21%].

Some examples of deviant dosing included:

Condition

Medication and dosage ordered

66 kg

DKA

Insulin continuous infusion 3 units/h

90 kg

Methylprednisolone 185 mg

16.4 kg

Herpetic infection

Acyclovir 820 mg

5 kg

Fever/young infant

Ampicillin 90 mg/cefotaxime 130 mg

A complete review of all cases revealed no instance of a clin- ically significant adverse outcome due to medication dosing.

Pediatric medication dosing miscalculation [under/over-dosing] can result in devastating consequences. There is little published data on the frequency of resident dosing errors in a pediatric care setting. One prior study [2] noted a relatively lower rate of 6% pre- scribing errors by pediatric residents working in a clinic. We know of no prior published report specifically documenting the preva- lence of medication dosing errors by EM residents training in a pediatric emergency department [ED], a common scenario at aca- demic medical institutions.

In general, the ED setting can predispose to relatively higher risk for Medication errors [3,4]. Over-dosage is the most commonly documented medication error occurring in the pediatric emer- gency medicine population [5]. Prescriber error-rates in emer- gency medicine, even among attending level physicians, has been shown to occur twice as frequently for pediatric vs adult medica- tion dosage calculations [6].

Multiple factors can contribute to increased risk for medication dosing errors. The fast paced and frequently chaotic ED environ- ment can augment risk for miscalculations. There can be insuffi- cient oversite, as it is often impractical for supervisory attending level physicians to review all resident Medication orders prior to their administration. In addition, EM residents are relatively inex- perienced with pediatric weight-based dosing calculations.

Frequency of emergency medicine resident dosing miscalculations treating pediatric patients

Frequency of emergency medicine resident dosing miscalculations treating pediatric patients