Accuracy of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of consolidations when compared to chest computed tomography

a b s t r a c t

Objectives: Despite emerging evidences on the clinical usefulness of Lung ultrasound , international guide- lines still do not recommend the use of sonography for the diagnosis of pneumonia. Our study assesses the accu- racy of LUS for the diagnosis of Lung consolidations when compared to chest computed tomography .

Methods: This was a prospective study on an emergency department population complaining of respiratory symptoms of unexplained origin. All patients who had a Chest CT scan performed for clinical reasons were con- secutively recruited. LUS was targeted to evaluate lung consolidations with the morphologic characteristics of pneumonia, and then compared to CT. Results: We analyzed 285 patients. CT was positive for at least one consolidation in 87 patients. LUS was feasible in all patients and in 81 showed at least one consolidation, with a good inter-observer agreement (k = 0.83), sen- sitivity 82.8% (95% CI 73.2%-90%) and specificity 95.5% (95% CI 91.5%-97.9%). Sensitivity raised to 91.7% (95% CI 61.5%-98.6%) and specificity to 97.4% (95% CI 86.5%-99.6%) in patients complaining of pleuritic chest pain. In a subgroup of 190 patients who underwent also chest radiography (CXR), the sensitivity of LUS (81.4%, 95% CI 70.7%-89.7%) was significantly superior to CXR (64.3%, 95% CI 51.9%-75.4%) (Pb.05), whereas specificity

remained similar (94.2%, 95% CI 88.4%-97.6% vs. 90%, 95% CI 83.2%-94.7%).

Conclusions: LUS represents a reliable diagnostic tool, alternative to CXR, for the bedside diagnosis of lung consol- idations in patients with respiratory complains.

(C) 2015

Introduction

Pneumonia is a common disease characterized by an infection that involves alveoli, distal airways, and interstitium, and leads to lung in- flammatory consolidations. Chest computed tomography (CT) is con- sidered the gold standard imaging test for the diagnosis of pulmonary

consolidations, but its routine application for the diagnosis of pneumo- nia is limited by concerns about the high radiation exposure and high costs [1,2]. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of pneumonia is based on clinical signs and supported by the visualization of typical opacities on chest radiography (CXR). However, in patients evaluated in the emer- gency department (ED), CXR showed a poor sensitivity (43.5%) when

? Author contributions: Dr. Nazerian is the guarantor of the manuscript. Dr Nazerian: contributed to study conception and design and data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, edit the manuscript for important intellectual and scientific content; served as the principal author; edited the revision; and approved the final draft. Dr Volpicelli: contributed to study design, drafted and edited for important intellectual and scientific content, edit the revision and approved the final draft. Dr Vanni: contributed to study conception

and design, conduct statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript, edited the revision and approved the final draft. Dr Betti: contributed to data acquisition, conducted statistical analysis, edited the revision and approved the final draft. Dr Gigli: contributed to data acquisition, conducted statistical analysis, edited the revision, and approved the final draft. Dr Bartolucci: contributed to data acquisition, and approved the final draft. Dr Zanobetti: contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafted and edited for important intellectual and scientific content and approved the final draft. Dr. Ermini: contributed to data acquisition, edited the revision, and approved the final draft. Dr. Iannello: edited the revision and approved the final draft. Dr Grifoni: contributed to data analysis and interpretation and approved the final draft.

?? All the authors have participated in the preparation of and read and approved the final manuscript.

?? Disclosures: the authors have no potential conflict of interest to disclose The article has never been presented.

* Corresponding author at: Department of Emergency Medicine, Careggi University Hospital, largo Brambilla 3, 50134 Firenze, Italy. Tel.: +39 3396122448, +39 0557947322; fax: +39 0557947147.

E-mail address: [email protected] (P. Nazerian).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.01.035

0735-6757/(C) 2015

compared to CT [3]. Therefore, reliance on CXR to diagnose pneumonia may lead to significant rates of misdiagnosis.

lung ultrasonography (LUS) is a bedside diagnostic tool that showed high sensitivity for the diagnosis of various pulmonary conditions, in- cluding pneumonia [4-9]. However, an important limitation of some of these previous studies is that not always CT was used as the gold stan- dard to confirm a pulmonary consolidation.

The aim of our study was to define the diagnostic performance of LUS in detecting pulmonary consolidations with the morphologic char- acteristics of pneumonia, using chest CT as the gold standard.

Material and methods

Study subjects and design

This was a prospective accuracy study, approved by the local institu- tional review board. Written informed consent was obtained for inclu- sion in the study. The patients were recruited from December 2011 to August 2012 in the ED of an Italian university hospital with an annual census of 120000 visits. Consecutive patients aged N 18 years with at least one unexplained respiratory complaint among dyspnea, chest pain, cough or hemoptysis, for which the attending emergency physi- cian ordered a chest CT during the diagnostic work up, were included in the study. Trauma patients were excluded from the study.

Methods

LUS was performed before and within three hours from chest CT by one of eight sonographer investigators who participated to the study. The investigators were four internal and emergency medicine attending physicians with at least 5 years experience of point-of-care emergency ultrasonography and four resident physicians (2 in internal medicine and 2 in emergency medicine) with at least one year training in emer- gency ultrasound. The investigators were aware of the presenting symptoms and the most visible physical signs, but were blinded to all the other general clinical information including radiologic findings. The following multi-probe machines were used: MyLab30 Gold (Esaote, Genova, Italy) and HD7 (Philips, Amsterdam, Holland).

LUS was performed by using a 4- to 8-MHz Linear probe or a 3.5- to 5-MHz curved array probe. The lung was examined by longitudinal and oblique scans on anterior, lateral and posterior chest. The patient was preferably examined in the sitting position. When this latter position could not be maintained, due to critical clinical conditions or poor com- pliance, the examination was performed in the supine or semi- recumbent position. The posterior areas were scanned in the sitting po- sition or, when not feasible, by turning the patient in the lateral decubitus on both sides. The LUS examination was targeted to the de- tection of typical subpleural lung consolidations with tissue-like or an- echoic pattern and blurred, irregular margins [10]. The consolidations due to pneumonia usually contain dynamic air bronchograms (branching echogenic structures with centrifuge movement with breathing) or multiple hyperechogenic lentil-sized spots, due to air trapped in the small airways, with associated focal B-lines [10-15]. Air bronchograms and focal B-lines were annotated and only used for con- firmation in case of doubtful pattern (Video 1). Other types of consolida- tions i.e. small pleural-based well-demarcated echo-poor triangular, rounded or polygonal consolidations with absence of air inclusions named subpleural infarcts often associated with pulmonary embolism were not considered [16-18]. Each hemithorax was divided into anterior-lateral areas (extending from parasternal to posterior axillary line) and posterior areas (from the posterior axillary to paravertebral line). Each area was divided into upper and lower halves, so that four areas per side were examined in each enrolled patient. LUS was consid- ered positive when at least one consolidation showing the above- described features was detected. Immediately after the completion of the LUS examination, the investigator filled in a standardized form,

eventually reporting the chest area where the consolidation was detect- ed (supplementary appendix). In a subgroup of 30 randomized patients, a second sonographer investigator performed LUS to evaluate the inter- observer agreement.

CXR was performed only when ordered by the treating physician, using a Practix 300 Bucky diagnostic equipment (Philips Medical Sys- tems, Hamburg, Germany) by posterior-anterior and lateral views in the upright patients, and anterior-posterior view in the Supine patients. The film was digitally reviewed by an expert radiologist blinded to the results of LUS and CT. The radiologist had the possibility to review also previous CXR, when available, as part of standard clinical care. The radi- ologist was asked to detect and locate the opacities that might be corre- lated with the diagnosis of pneumonia. CXR was considered positive when at least one typical consolidation was visualized.

Chest CT was performed by one Somatom Definition AS128 (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), only for clinical purposes and indepen- dently from the study protocol. An expert radiologist, other than the at- tending radiologist and blinded to LUS and CXR results, reviewed the studies and reported number and location of the consolidations. The ra- diologist filled in a standardized form that was similar to the one used by the ultrasound investigator (Supplementary appendix). CT repre- sented the gold standard and was considered positive for pneumonia when at least one typical consolidation was detected. To this purpose, the radiologist who interpreted the CT image was blinded to any clinical in- formation and was concentrated on the pure morphologic characteristics of the consolidation. A second radiologist reviewed all chest CT studies to evaluate inter-observer agreement. In patients without any visible con- solidation on chest CT, an independent investigator (SG) established the alternative diagnosis after reviewing all available clinical data and medical records.

Consolidations diagnosed on CXR and CT were defined as homoge- neous increase in pulmonary parenchymal attenuation obscuring the margins of vessels and airway walls, with or without air bronchograms [19-21].

Analysis

Data points are expressed as mean +- SD. The unpaired Student t test was used to compare normally distributed data. Fisher exact test was used for the comparison of non-continuous variables expressed as pro- portions. P b .05 indicates statistical significance. All P values are 2 sided. The diagnostic performance of LUS and of CXR was assessed by calculat- ing sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and likelihood ratios. The extended McNemar and the McNemar tests were used to evaluate if there was a significant difference in the sensitivities and specificities of LUS and CXR [22]. The diagnostic perfor- mance of LUS for detecting consolidation in each of the eight chest areas was also calculated. The k statistic was calculated to assess Interobserver agreement of LUS and chest CT [23]. Calculations were performed by using SPSS statistical package (version 17.0; IBM).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 308 patients with respiratory complains underwent chest CT in the ED during the study period. Four patients did not consent to participate. In 19 patients LUS was not performed before chest CT or within the time limit. Thus, 285 patients were included in the final anal- ysis (Fig. 1). These patients had a mean age of 71+-14 years (range, 23-100) and 152 (53.3%) were women. Chest CT was positive for at least one consolidation in 87 patients (30.5%), with an almost perfect agreement between the two radiologists (k = 0.94). The patients’ char- acteristics according to chest CT results are shown in Table 1. The alter- native diagnoses in patients with negative chest CT are reported in Table 2. The total number of lung areas positive for consolidation at

pneumonia

n = 81 (28.4%)

Final diagnosis of pneumonia n = 72 (25.3%)

Alternative final diagnosis n = 9 (3.2%)

Enrolled patients n = 308

Excluded patients:

n = 4 (did not consent)

n = 19 (lung US not performed)

Included patients n = 285

Lung ultrasonograpy

Alternative final diagnosis n = 189 (66.3%)

Final diagnosis of pneumonia n = 15 (5.3%)

Negative for

pneumonia

n = 204 (71.6%)

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the study and main results % refers to the 285 included patients.

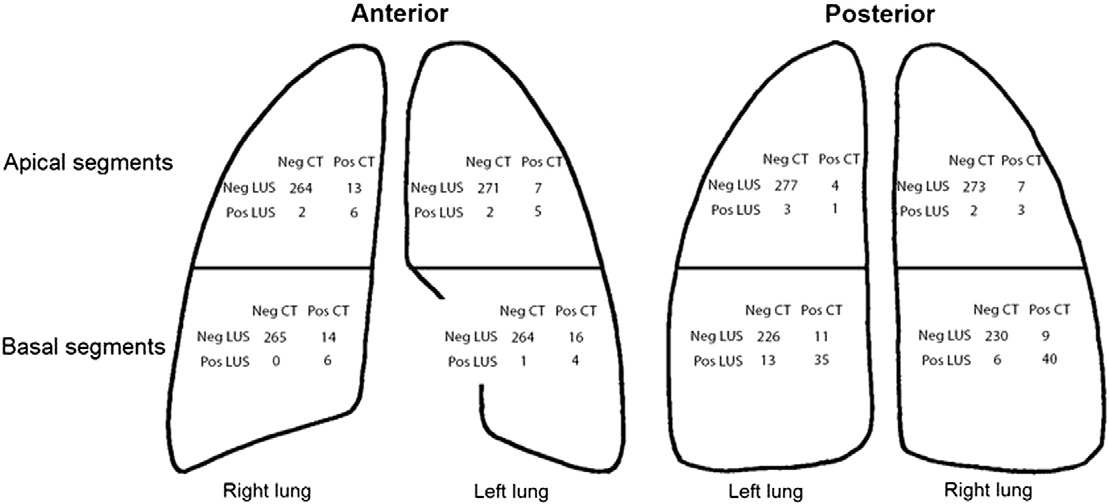

chest CT was 181, with a mean of 2.1 per patient. The lower posterior areas were the most affected (95 areas, 52.5%) (Fig. 2).

Main results

LUS was feasible in all patients, but in 21 cases (7.4%) pulmonary ex- amination was limited only to the anterior-lateral areas. In 165 patients (57.9%) LUS was performed by attending physicians and in 120 cases (42.1%) by resident physicians.

LUS was positive for at least one consolidation in 81 patients (28.4%). Seventy-two (88.9%) out of 81 patients with positive LUS also had pos- itive chest CT (Fig. 1). LUS showed false positive examination in 9 cases

Characteristics of the study population according to positive lung CT (at least one inflam- matory consolidation detected)

(3.1%), which corresponded in 3 cases to Lung cancer nodules (visualized at CT and confirmed by histology), in 3 cases to areas of pa- renchymal impaired ventilation not due to infection, and in 3 cases to fi- brotic bands. LUS showed false negative examination in 15 patients (5.3%). In 3 of these cases the posterior consolidations were not detect- ed because LUS was performed only on anterior-lateral chest. In other 5 cases the consolidations were located deep in the lung parenchyma without any contact with the parietal pleura. Overall test characteristics of LUS are reported in Table 3. Inter-observer agreement of LUS between two investigators was almost perfect (k = 0.831).

In a subgroup of patients complaining of pleuritic chest pain (n = 51, 17.9%), sensitivity and specificity of LUS were 91.7% (95% CI 61.5-98.6%) and 97.4% (95% CI 86.5-99.6%), respectively, whereas in the subgroup of patients without pleuritic chest pain sensitivity and specificity of LUS were 81.3% (95% CI 70.7-89.4%) and 95% (95% CI 90.3-97.8%),

respectively.

The total number of lung areas positive for consolidations at LUS was

Characteristics Positive

lung CT (n = 87)

Negative P

lung CT (n = 198)

129 with a mean of 1.6 per patient. Fig. 2 and Table 4 show the diagnos- tic accuracy and performance of LUS in different lung areas.

In 190 patients CXR studies were also available for the analysis. In

Mean age +- SD, y 70.3 +- 17.8 71.9 +- 12.6 .377

Women 39 (44.8) 113 (57.1) .071

Medical history of lung disease

this subgroup, the sensitivity of LUS (81.4%, 95% CI 70.7-89.7%) was

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

16 (18.4) |

29 (14.6) |

.481 |

Table 2 |

|

Fibrosis |

1 (1.1) |

5 (2.5) |

.671 |

Alternative diagnosis in the 198 patients with negative chest CT (no inflammatory consol- |

|

Malignancy |

3 (3.4) |

18 (9.1) |

.138 |

idation detected) |

|

Previous pneumonectomy Previous pulmonary embolism |

1 (1.1) 1 (1.1) |

4 (2) 12 (6.1) |

1 .118 |

Diagnosis |

No. (%) |

|

Signs and symptoms at presentation |

Pulmonary embolism |

74 (37.4) |

|||

|

Dyspnea |

59 (67.8) |

116 (58.6) |

.149 |

Heart failure |

22 (11.1) |

|

Cough |

33 (37.9) |

27 (13.6) |

b.001 |

Pleural effusion |

14 (7.1) |

|

Purulent expectoration |

17 (19.5) |

12 (6.1) |

.001 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

13 (6.6) |

|

Hemoptysis |

6 (6.9) |

1 (0.5) |

.004 |

Tachyarrhythmia |

12 (6) |

|

Pleuritic chest pain |

12 (13.8) |

39 (19.7) |

.314 |

Musculoskeletal chest pain |

11 (5.5) |

|

Shock/hypotension |

22 (25.3) |

17 (8.6) |

b.001 |

Acute coronary syndrome |

10 (5) |

|

23 (26.4) |

27 (13.6) |

.011 |

Sepsis with no pulmonary involvement |

5 (2.5) |

|

|

HR N 100 bpm |

53 (60.9) |

82 (41.4) |

.003 |

5 (2.5) |

|

|

Mean SpO2 +- SD, % |

91.8 +- 6.27 |

94.3 +- 4.96 |

.003 |

Respiratory failure in pulmonary malignancy |

5 (2.5) |

|

Mechanical invasive ventilation |

7 (8) |

4 (2) |

.038 |

Pericardial effusion/pericarditis |

2 (1) |

Data are given as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. HR, heart rate; bpm = beats/min.

Miscellaneous 25 (12.6)

Fig. 2. Positive and negative results of lung ultrasonography and chest computed tomography in different chest areas. Neg, Negative (no consolidation detected in the chest area); Pos, positive (at least one consolidation detected in the chest area).

higher than CXR (64.3%, 95% CI 51.9-75.4%) with a p value of 0.036,

whereas specificities were similar (94.2%; 95% CI, 88.4-97.6% vs 90%;

95% CI, 83.2-94.7%; P = .332).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that LUS is a reliable tool for the diagnosis of pneumonia-related lung consolidations, when chest CT imaging is used as the gold standard, in adults with respiratory complains of unex- plained origin. Our data showed that LUS rules in consolidations with the radiologic characteristics of pneumonia with a high positive likeli- hood ratio (+LR= 18.2, 95% CI 9.6-34.7) and rules out this condition with a moderate negative likelihood ratio (-LR= 0.18, 95% CI 0.1-0.3). These findings are comparable to previous studies [4-7,24-28].

However, for the very first time, our study was based on a systematic morphologic comparison of LUS with chest CT in a consistent number of ED patients. Comparison with CT imaging represents the optimal study procedure to assess the test performance characteristics of LUS in vivo. Three previous studies on LUS used CT as the gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in the whole sample [5,28,29]. However, these studies were all performed only on critically ill patients admitted to an intensive care unit and, mostly, during invasive ventilation. Two of these studies evaluated the potential of LUS in the general evaluation of the critically ill, thus including also pulmonary consolidations among the other conditions [28,29]. Only the third study was specifically de- signed to evaluate the potential of LUS for pulmonary consolidations and used CT as the gold standard, similarly to our protocol. [5] However, besides being limited by the observation of a selected population of crit- ically ill patients, the study analyzed a small number of patients and was performed by only two operators [5].

Even though we found a high specificity of LUS, similar to the values found in these previous studies, the sensitivity in our study was lower. The difference in the populations studied may explain this discrepancy, particularly when the mixed population of the ED and the critically ill patients from the intensive care unit are compared. Some of the false

negative examinations of our study were obtained in patients whose clinical conditions were not severely compromised. These patients sometimes show small consolidations without any contact with the lung periphery. Indeed, we know that one important limitation of LUS is its inability to visualize deep pulmonary lesions that are limited in se- verity and extension, and are not in contact with the pleura [10]. More- over, in some cases LUS may also be limited by the impossibility to examine the whole chest, particularly in bedridden patients or in case of bandages, wounds, pads and devices that may hinder the direct con- tact between the probe and some chest areas.

In our study protocol LUS was feasible in the vast majority of pa- tients, even if in some cases the technique was forcedly incomplete due to the impossibility to scan the dorsal areas, mainly in unstable pa- tients. However, this limitation is still minimal when compared to the consistent difficulty of performing a complete two-views upright CXR study, which is a serious concern, particularly in the emergency setting [30].

We observed a high inter-observer agreement on the interpretation of LUS imaging, even though the level of expertise of the operators was variable. Only two previous studies assessed the ability of non-expert physicians to perform LUS to diagnose pneumonia. For this reason, a re- cent meta-analysis on the topic concluded that the lack of strong evi- dence precludes the ability to recommend the use of LUS for pneumonia in general practitioners [31]. The possibility to extend the use of LUS also to general practitioners, without limiting its application to few selected top-level experts, is of great importance to spread the technique. Our data on the high inter-observer agreement between mixed operators provide a further contribution, mainly because they are opposed to the high inter-observer variability reported among ex- perts radiologists and other physicians in the interpretation of chest film reading [3,32,33].

Our study was also designed to evaluate the performance of LUS to identify the correct anatomic location of the pulmonary consolidations, which represents a novelty in the literature. In our analysis, while spec- ificity of LUS for pulmonary consolidations was constantly good in every

Accuracy of lung ultrasonography and chest radiograph considering chest CT as gold standard

|

Lung US and chest radiograph |

Sens % (95% CI) |

Spec % (95% CI) |

PPV % (95% CI) |

NPV % (95% CI) |

+LR (95% CI) |

-LR (95% CI) |

|

LUS in all pts |

82.8 (73.2-90) |

95.5 (91.5-97.9) |

88.9 (80-94.8) |

92.7 (88.2-95.8) |

18.2 (9.6-34.7) |

0.18 (0.1-0.3) |

|

LUS in the 264 pts with anterior and posterior scans |

86.4 (77-93) |

95.1 (90.9-97.7) |

88.6 (79.5-94.6) |

94.1 (89.6-97) |

17.6 (9.2-33.4) |

0.14 (0.08-0.25) |

|

LUS in 51 pts with pleuritic chest pain |

91.7 (61.5-98.6) |

97.4 (86.5-99.6) |

91.7 (61.5-98.6) |

97.4 (86.5-99.6) |

35.8 (5.1-249.3) |

0.09 (0.01-0.56) |

|

Chest radiograph in 190 pts |

64.3 (51.9-75.4) |

90 (83.2-94.7) |

78.95 (66.1-88.6) |

81.2 (73.5-87.5) |

6.43 (3.7-11.3) |

0.4 (0.29-0.55) |

US, ultrasonography; pts, patients; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, Negative predictive value; +LR, Positive likelihood ratio; -LR, negative likeli- hood ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Accuracy of lung ultrasonography for consolidation in different chest areas

|

Chest areas |

Sens % (95% CI) |

Spec % (95% CI) |

PPV % (95% CI) |

NPV % (95% CI) |

+LR (95% CI) |

-LR (95% CI) |

|

Antero-lateral upper halves |

35.5 (19.3-54.6) |

99.3 (98.1-99.8) |

73.3 (44.9-92.1) |

96.4 (94.5-97.8) |

47.8 (16.2-141.6) |

0.65 (0.5-0.8) |

|

Antero-lateral lower halves |

25 (12.7-41.2) |

99.8 (98.9-100) |

90.9 (58.7-98.5) |

94.6 (92.4-96.4) |

132.5 (17.4-1009) |

0.75 (0.6-0.9) |

|

Posterior upper halves |

26.7 (8-55.1) |

99.1 (97.9-99.7) |

44.4 (14-78.6) |

98 (96.5-99) |

29.6 (8.8-99.3) |

0.74 (0.6-1) |

|

Posterior lower halves |

78.9 (69.4-86.6) |

96 (93.8-97.6) |

79.8 (70.3-87.4) |

95.8 (93.6-97.4) |

19.7 (12.6-31) |

0.2 (0.15-0.3) |

US, ultrasonography; pts, patients; Sens, sensibility; Spec, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; +LR, positive likelihood ratio; -LR, negative likeli- hood ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

chest area, sensitivity significantly improved in the prediction of consol- idations located in the posterior lower halves. Consolidations located in basal zones are well imaged by LUS mainly because they are frequently associated with pleural effusion, which often collects in the most depen- dent chest areas. Even the smallest effusion contributes to enhance the acoustic window, yielding a better image resolution. However, consid- eration of basal consolidations may lower specificity because, particu- larly in critically ill patients, other causes than infection may produce consolidative processes, i.e. mechanic compression and impaired venti- lation producing atelectasis of the lung bases [34].

The superiority of LUS over CXR in the diagnosis of pulmonary con- solidations is largely demonstrated in literature [6,7,10]. In our study, despite similar specificities, the sensitivity of LUS was superior to CXR. pleuritic pain may even increase the ability of LUS in the detection of pulmonary conditions, because this symptom allows to focus the initial ultrasound examination to a limited chest area [10]. Previous studies showed that LUS might detect radio-occult pulmonary lesions when the examination is guided by localized pain [8,35,36]. In our study, sen- sitivity of LUS increased in the subgroup of patients complaining of pleuritic chest pain at presentation, thus confirming the peculiarity of this diagnostic model that may increase the potential of LUS for the di- agnosis of pulmonary consolidations.

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. A questionable characteristic of our protocol is that patients were not enrolled on the basis of a suspicion for pneumonia. We concentrated our study on patients who demanded CT scan for ambiguous diagnosis. In case of suspected uncomplicated lung infection, where the diagnosis is mainly based on clinical findings and CXR, it is unusual to undergo CT scans. Therefore, studying a population with unexplained respiratory complains requiring a chest CT study may have the consequence to diagnose even the smallest consolidations, thus reducing LUS sensitivity. Instead, the ideal study should enroll pa- tients only when pneumonia is strongly suspected. However, a system- atic application of CT studies even without a strong clinical indication is not ethical and not feasible.

Our analysis was focused only on the ability of LUS to correspond with CT the pure diagnosis of the anatomic correlate of pneumonia that is the pulmonary consolidation with the characteristics of shape and far-field features explained in the methods. This correlation not necessarily corresponded to a confirmed clinical diagnosis of pneumo- nia, which remains a clinical condition that cannot be only based on the analysis of the CT image. For this reason, our study can only conclude on the ability of lung ultrasound to perform a pure morphologic diagno- sis of lung consolidations related to pneumonia.

In addition to the consolidated pattern and evaluation of its margins, other LUS signs may be useful to better define the etiology of the consol- idation, like the characteristics of fluid and air bronchograms and the type of vascularization. We annotated in our standardized form some of these signs as adjunctive findings, but did not analyze their perfor- mance in the differential diagnosis of consolidations. Moreover, we did not consider the usefulness of the analysis of the B-lines. These arti- facts are often detected in a focal chest area surrounding the consolida- tion, and indicate a higher degree of lung aeration, although still sub- normal, compared with the consolidated area that is characterized by

a complete loss of alveolar air. Some studies evaluated this sign, namely “the focal interstitial syndrome”, as an ultrasound pattern that may pre- dict pneumonia, infarctions, contusions [8,37]. Whether taking into con- sideration the focal interstitial pattern may change the diagnostic performance of LUS for pneumonia, remains unexplored, but it is logical to expect that sensitivity of LUS may be improved at the expense of its specificity.

Conclusions

LUS is a reliable method for the diagnosis of pulmonary consolida- tions when compared to chest CT in patients with respiratory complains of unexplained origin. Ultrasonography has certain advantages over CXR and may be considered a valid alternative for the diagnosis of pneu- monia. LUS is highly feasible and its application in the ED may be ex- tended to physicians with different levels of expertise, still maintaining a high diagnostic accuracy.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.01.035.

References

- Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography-an increasing source of radiation expo- sure. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2277-84.

- Esayag Y, Nikitin I, Bar-Ziv J, Cytter R, Hadas-Halpern I, Zalut T, et al. Diagnostic value of chest radiographs in bedridden patients suspected of having pneumonia. Am J Med 2010;123:88.e81-5.

- Self WH, Courtney DM, McNaughton CD, Wunderink RG, Kline JA. High discordance of chest x-ray and computed tomography for detection of pulmonary opacities in ED patients: implications for diagnosing pneumonia. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:401-5.

- Cortellaro F, Colombo S, Coen D, Duca PG. Lung ultrasound is an accurate diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of pneumonia in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2012;29:19-23.

- Lichtenstein DA, Lascols N, Meziere G, Gepner A. ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:276-81.

- Parlamento S, Copetti R, Di Bartolomeo S. Evaluation of lung ultrasound for the diag- nosis of pneumonia in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2009;27:379-84.

- Reissig A, Copetti R, Mathis G, Mempel C, Schuler A, Zechner P, et al. Lung ultrasound in the diagnosis and follow-up of community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, multicenter, diagnostic accuracy study. Chest 2012;142:965-72.

- Volpicelli G, Caramello V, Cardinale L, Cravino M. Diagnosis of radio-occult pulmo- nary conditions by real-time chest ultrasonography in patients with pleuritic pain. Ultrasound Med Biol 2008;34:1717-23.

- Zanobetti M, Poggioni C, Pini R. Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED? Chest 2011;139:1140-7.

- Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, Lichtenstein DA, Mathis G, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. International Liaison Committee on Lung Ultrasound for International Consensus Conference on Lung Ultrasound. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:577-91.

- Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014;20: 315-22.

- Mathis G, Dirschmid K. Pulmonary infarction: sonographic appearance with patho- logic correlation. Eur J Radiol 1993;17:170-4.

- Reissig A, Kroegel C. Transthoracic ultrasound of lung and pleura in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a novel non-invasive bedside approach. Respiration 2003;70: 441-52.

- Lichtenstein D, Meziere G, Seitz J. The dynamic air bronchogram. A lung ultrasound sign of alveolar consolidation ruling out atelectasis. Chest 2009;135:1421-5.

- Volpicelli G, Caramello V, Cardinale L, Mussa A, Bar F, Frascisco MF. Detection of sonographic B-lines in patients with normal lung or radiographic alveolar consolida- tion. Med Sci Monit 2008;14:CR122-8.

- Hoffmann B, Gullett JP. Bedside transthoracic sonography in suspected pulmonary embolism: a new tool for emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:e88-93.

- Mathis G, Blank W, Reissig A, Lechleitner P, Reuss J, Schuler A, et al. Thoracic ultra- sound for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicenter study of 352 patients. Chest 2005;128:1531-8.

- Nazerian P, Vanni S, Volpicelli G, Gigli C, Zanobetti M, Bartolucci M, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care multiorgan ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Chest 2014;145:950-7.

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Muller NL, Remy J. Fleischner So- ciety: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008;246:697-722.

- Leung AN, Miller RR, Muller NL. Parenchymal opacification in chronic infiltrative lung diseases: CT-pathologic correlation. Radiology 1993;188:209-14.

- Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, Huchon G, Ieven M, Ortqvist A, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J 2005;26: 1138-80.

- Hawass NE. Comparing the sensitivities and specificities of two diagnostic proce- dures performed on the same group of patients. Br J Radiol 1997;70:360-6.

- McGinn T, Wyer PC, Newman TB, Keitz S, Leipzig R, For GG. Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 3. Measures of observer variability (kappa statistic). CMAJ 2004;171:1369-73.

- Caiulo VA, Gargani L, Caiulo S, Fisicaro A, Moramarco F, Latini G, et al. Lung ultra- sound characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48:280-7.

- Shah VP, Tunik MG, Tsung JW. Prospective evaluation of point-of-care ultrasonogra- phy for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:119-25.

- Testa A, Soldati G, Copetti R, Giannuzzi R, Portale G, Gentiloni-Silveri N. Early recog- nition of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia by chest ultrasound. Crit Care 2012;16:R30-9.

- Tsung JW, Kessler DO, Shah VP. Prospective application of clinician-performed lung ultrasonography during the 2009 H1N1 influenza A pandemic: distinguishing viral from Bacterial pneumonia. Crit Ultrasound J 2012;4:16-25.

- Xirouchaki N, Kondili E, Prinianakis G, Malliotakis P, Georgopoulos D. Impact of lung ultrasound on clinical decision making in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:57-65.

- Lichtenstein D, Goldstein I, Mourgeon E, Cluzel P, Grenier P, Rouby JJ. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasonogra- phy in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology 2004;100:9-15.

- Syrjala H, Broas M, Suramo I, Ojala A, Lahde S. High-resolution computed tomography for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:358-63.

- Chavez MA, Shams N, Ellington LE, Naithani N, Gilman RH, Steinhoff MC, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Respir Res 2014;15:50-8.

- Albaum MN, Hill LC, Murphy M, Li YH, Fuhrman CR, Britton CA, et al. Interobserver reliability of the chest radiograph in community-acquired pneumonia. PORT Investi- gators. Chest 1996;110:343-50.

- Campbell SG, Murray DD, Hawass A, Urquhart D, Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Maxwell D. Agreement between emergency physician diagnosis and radiologist reports in pa- tients discharged from an emergency department with community-acquired pneu- monia. Emerg Radiol 2005;11:242-6.

- Lichtenstein DA, Meziere GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest 2008;134:117-25.

- Volpicelli G, Cardinale L, Berchialla P, Mussa A, Bar F, Frascisco MF. A comparison of different diagnostic tests in the bedside evaluation of pleuritic pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:317-24.

- Volpicelli G, Frascisco M. Lung ultrasound in the evaluation of patients with pleuritic pain in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2008;34:179-86.

- Soldati G, Testa A, Silva FR, Carbone L, Portale G, Silveri NG. Chest ultrasonography in lung contusion. Chest 2006;130:533-8.