Very brief training for laypeople in hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Effect of real-time feedback

a b s t r a c t

Background: Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) improves survival from out-of-hospital cardiac ar- rest, but rates and performance quality remain low. Although training laypeople is a primary educational goal, the optimal strategy is not well defined. This study aimed to determine whether a short training with real- time feedback was able to improve Hands-only CPR among untrained citizens.

Methods: On the occasion of the 2015 World Heart Day and the European Restart a Heart Day, a pilot study involv- ing 155 participants (81 laypeople, 74 health care professionals) was conducted. Participants were invited to briefly practice hands-only CPR on a manikin and were after evaluated during a 2-minute chest compression test. During training brief instructions regarding hand position, compression rate and depth according to the current guidelines were given and real-time feedback was provided by a Laerdal SkillReporting System.

Results: Mean CC rate was significantly higher among health care professionals than among laypeople (119.07 +- 12.85 vs 113.02 +- 13.90 min-1; P = .006), although both met the 100-120 CC min-1 criterion. Laypeople achieved noninferior results regarding % of CC at adequate rate (51.46% +- 35.32% vs health care staff (55.97% +- 36.36%; P = .43) and depth (49.88% +- 38.58% vs 50.46% +- 37.17%; P = .92), % of CC with full-chest recoil

(92.77% +- 17.17% vs 0.91% +- 18.84; P = .52), and adequate hand position (96.94% +- 14.78% vs 99.74 +- 1.98%; P = .11). The overall Quality performance was greater than 70%, noninferior for citizens (81.23% +- 20.10%) vs health care staff (85.95% +- 14.78%; P = .10).

Conclusion: With a very brief training supported by hands-on instructor-led advice and visual feedback, naive laypeople are able to perform good-quality CC-CPR. Simple instructions, feedback, and motivation were the key elements of this strategy, which could make feasible to train big numbers of citizens.

(C) 2016

Sudden cardiac death is for many individuals the first manifestation of cardiovascular disease , usually on the presence of an ischemic

* Corresponding author at: cardiology department, Hospital Clinico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, A Choupana s/n. 15706, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruna, Spain. Tel.: +34 981 950 793; fax: +34 981 950 534.

E-mail address: [email protected] (V. Gonzalez-Salvado).

1 SAMID-II Network. RETICS funded by the PN I+D+I 2008-2011 (Spain), ISCIII-Sub- Directorate General for Research Assessment and Promotion and the European Regional Development Fund, Ref. RD12/0026.

substrate [1,2]. At least half of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCAs) are witnessed [3-6]. Although bystander initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and Early defibrillation significantly increase surviv- al compared with no CPR [3,6-10], rates of bystander initiated CPR re- main worryingly low [11,12]. Therefore, training general population in basic CPR skills is a primary educational goal, as expressly noted in the current Resuscitation guidelines [13,14].

Prompt delivery of high-quality chest compression-CPR (CC-CPR) provides critical perfusion to the heart and brain and may prevent defibrillable rhythm from degenerating into asystole [15]. It has been proven to be at least as effective as conventional CPR in the out-of-

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2016.02.047

0735-6757/(C) 2016

hospital setting and easier to perform for untrained lay rescuers [16-20]. “Hands-only” CPR should be thus taught to all citizens as a min- imum requirement [13] and it may be a good approach when presented in public campaigns or mass events, where information should be fo- cused and clear.

Despite previous studies comparing a wide range of educational CPR strategies, the optimal training method is still to be defined. Overall fi- nancial, time, or motivational reasons are obstacles that limit citizens’ access to standard CPR courses [13,21], and new cost-effective ap- proaches are needed to reach general population. Recent studies have explored the usefulness of short training strategies, which have been suggested to be as effective as the former. Feedback [22-24], self- instructed learning [25,26], and competition [24,27] appear to be useful tools to strengthen CPR learning, although further research is needed to assess their impact on a real scenario.

In this study, we aimed to assess the usefulness of very brief practical training (b 5 minutes) on a manikin to improve CC-CPR skills among naive citizens. Simple instructions, real-time feedback, and motivation may have been the core elements of the proposed strategy.

- Methods

- Study design

The World Heart Day (29th September) and the European Restart Heart Day (16th October) are initiatives that aim to increase general awareness of the importance of cardiovascular prevention and Cardiac resuscitation [28,29]. As part of these events in 2015, a number of activ- ities to promote cardiovascular health and health education were orga- nized at our hospital, targeted at both health care staff and general population. One of these was a CPR learning station organized at the hospital hall. Volunteer instructors among medical and nursery staff from the cardiology department and the intensive care unit provided simple explanations about the importance of initiating the chain of sur- vival, the correct approach in case of cardiac arrest, and the use of the automatic external defibrillator. Besides, passing-by citizens and mem- bers from the health care staff had the chance to practice and test their ability to perform hands-only CPR on a Laerdal ResusciAnne manikin (Stavanger, Norway).

Participants volunteered to practice hands-only CPR on a manikin for 5 minutes and be after evaluated during a 2-minute continuous CC test. Data from technical performance were recorded by a Laerdal Com- puterized SkillReporting System and later analyzed.

Participants

Study participants were verbally recruited among citizens and mem- bers of the health care staff who passed-by the hospital lobby on the morning of these 2 event’s days.

All participants gave their verbal consent to participate. No personal information that could lead to their identification was recorded. Volun- teers were asked about their prior CPR training and health care people were asked about their professional status (doctor, nurse, medical or nursery student). Citizens with any prior CPR training, those younger than 18 years, and those who were unable to finish the 2-minute CC test were excluded.

CC-CPR training

Each participant was assigned to a Laerdal ResusciAnne manikin and one instructor. They were given brief explanations about the impor- tance of early initiation of basic life support in case of a witnessed cardi- ac arrest in order to increase the patient’s survival chances.

Simple instructions regarding hand position, compression depth, and rate according to the current resuscitation guidelines [30] were given by the instructors during 5 minutes of repetitive CC-CPR training.

Special emphasis was placed on the frequency of compressions, as par- ticipants were asked to remember and perform CC-CPR to the beat of popular song at 100 beats/min (La Macarena, by Los del Rio) [31].

CC-CPR quality testing

Just after the training, participants were evaluated during a 2- minute continuous CC test. Four Laerdal ResusciAnne manikins with Wireless SkillReporter software version 1.1 were used to assess real- time technical performance of CC-CPR.

Good-quality performance was considered when the participant ac- complished correct CC equal or higher than 70% [32,33] according to the current recommendations of compression depth (50-60 mm), rate (100-120 per minute), complete chest recoil, and correct hand position on the chest [30].

Study variables

The variables explored were age and a number of CPR quality met- rics including total number of CC, mean CC rate (in CC per minute), mean CC depth (in millimeters), percentage of CC at adequate rate, % of CC at adequate depth, % of CC with correct hand position, and % of CC with full-chest recoil. Global quality of CC-CPR (QCPR) was calculat- ed by the Laerdal SkillReporter software, using the standard algorithm, which combines % of CC at adequate and rate depth, % of CC with correct hand position, and % of CC with full-chest recoil, as shown in Fig. 1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Mac, version 20 (SPSS Inc, IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics included mean, SD, and 95% confidence interval. Levene test was used to assess the ho- mogeneity of variances. Unpaired t test for continuous variables was used to compare differences between means between both groups. In all analyses, a significance level of P b .05 was considered.

- Results

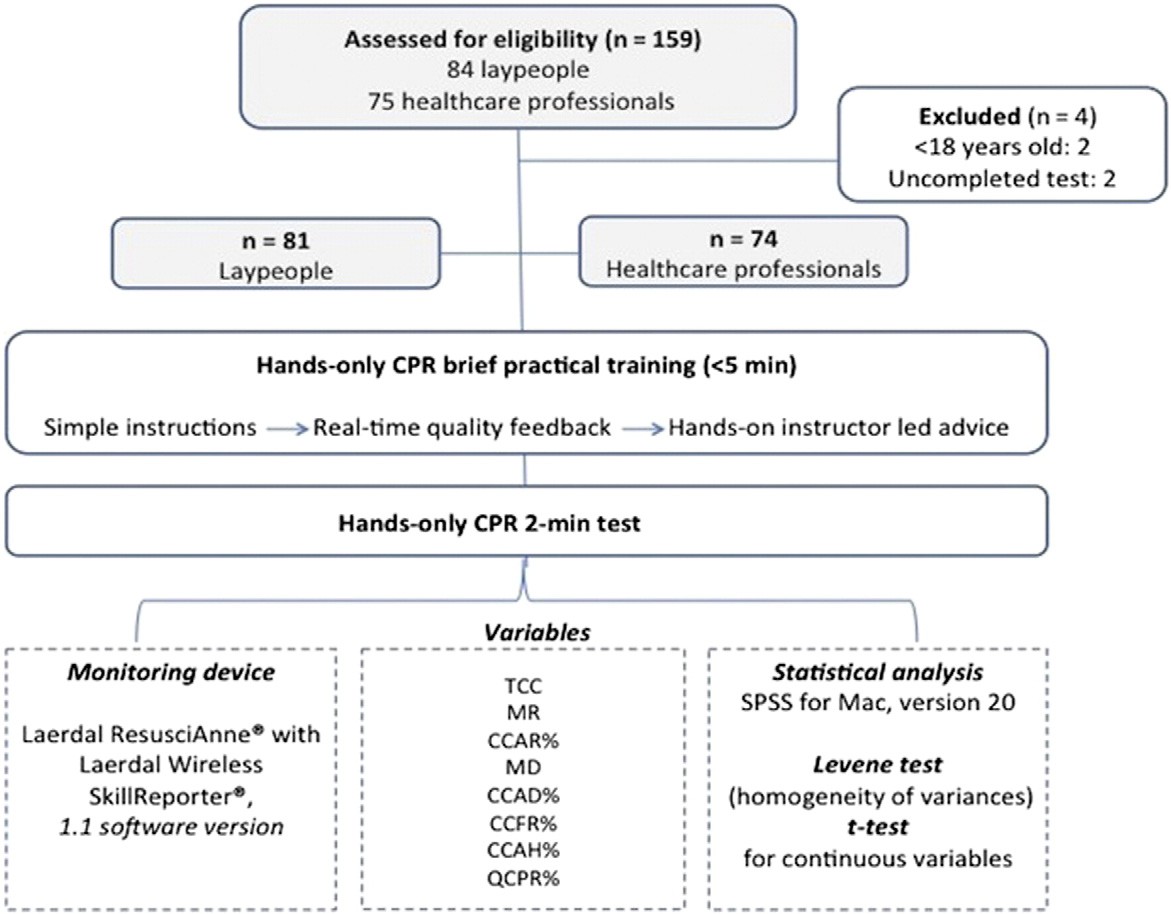

From the 159 recruited, 2 laypeople younger than 18 years as well as 1 participant in each group who had not completed the 2-minute test were excluded. The final sample included 74 health care professionals and 81 laypeople. Fig. 2 illustrates the flow diagram for our study. Partic- ipants’ age and results of CPR quality metrics for both groups are shown in Table 1.

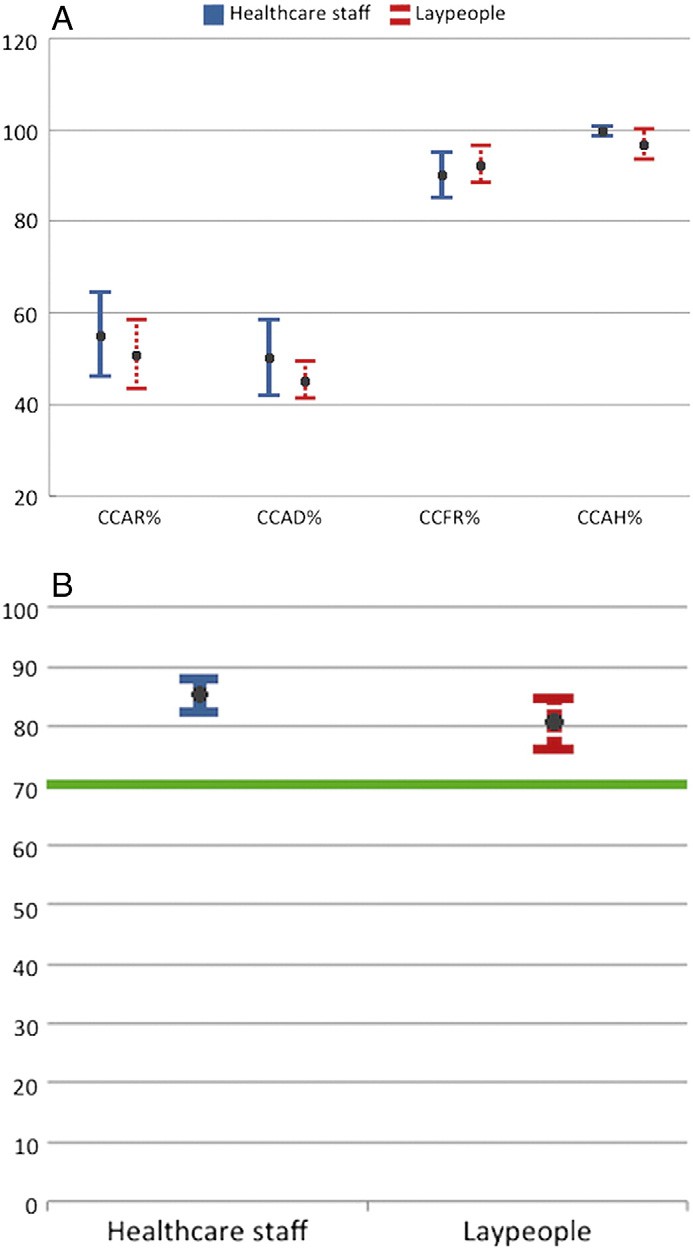

During the 2-minute test, both groups met the CC rate criterion of 100 to 120 min-1, although the rate was higher among health care pro- fessionals (119.07 +- 12.85 min-1) vs laypeople (113.02 +- 13.90 min-1; P = .006). Around half of the CC were delivered at the adequate rate (55.97% +- 36.36% vs 51.46% +- 35.32%; P = .43). Similarly, only around 50% of participants reached the recommended 50- to 60-mm compression depth in both samples (50.46% +- 37.17% vs 49.88% +- 38.58%; P = .92).

Regarding chest recoil, no significant differences were observed be- tween health care staff (90.91% +- 18.84%) and citizens (92.77% +- 17.17%; P = .52). Similar results were observed for hand position (99.74% +- 1.98% vs 96.94% +- 14.78%; P = .11).

Overall, CC-CPR performance assessed by the QCPR formula as previ- ously described was above the 70% goal for both groups. Slightly better but no significantly different results were achieved by the health care professionals (85.95% +- 14.78%) vs laypeople (81.23% +- 20.10%; P =

.10). The results are graphically represented in Fig. 3.

- Discussion

Cardiac arrest is a leading cause of death worldwide. Cardiovascular disease is the most frequent underlying condition, with coronary

Fig. 1. Hands-only CPR quality monitoring system. Global hands-only CPR quality was calculated for each participant by the Laerdal SkillReporter software, considering adequate rate and depth, correct hand position, and full-chest recoil.

ischemia accounting for approximately 80% of cases, which mainly occur in the out-of-hospital setting [4,6]. Because the burden of CVD parallels that of cardiac arrest, interventions performed to tackle CVD will carry an inherent reduction in the incidence of sudden cardiac death [1].

Cardiovascular prevention plays a central role in this regard. Efforts must be made to increase people awareness of their own responsibility to help CVD and its deleterious consequences, by means of health edu- cation [2]. Initiatives like the World Heart Day and the European Restart a Heart Day, respectively, encouraged by the World Heart Federation and the European Resuscitation Council, aim to promote cardiovascular health, modify risk factors, and enhance measures that will help in- crease the rate of survival for in-hospital and OHCA [28,29].

Despite that data are heterogeneous across the different European countries, survival rates from OHCA seem to be slowly improving in the last decades, but generally remain around 10% [3-5,34]. Because OHCAs are witnessed in at least half of cases, mostly by a bystander [3-5], and because bystander CC-CPR has shown to improve Survival and neurological outcomes of the arrested patient [3,7-10], all citizens should be taught how to perform good-quality CC-CPR as a minimum requirement, as well as be familiarized with the use of automatic exter- nal defibrillator [1,13,14].

Financial, time, or motivational issues usually limit the access to standard CPR training courses. Short and self-instructed learning programs have emerged in the last years, aimed at facilitating general access to CPR training [21], such as the CPR Anytime Program encour- aged by the American Heart Association [26]. Still, it is worrisome that rates of bystander CPR remain around a modest 30% [3,11,12], highlight- ing the need for new initiatives to increase public awareness of its relevance.

Even if reduced delay to medical attention and improved manage- ment after cardiac-related sudden death in acute coronary care units have resulted in substantial reductions in mortality [35], no formal

CPR training initiatives focused on general population are established in our hospital. Our study stems from the perceived need to fill this gap, by providing an accessible and effective formula that will help to prevent the deleterious consequences of OHCA from the very first link of the Chain of survival. Thus, on the occasion of the celebration of the World Heart Day and the Restart a Heart Day, we aimed to assess the usefulness of opportunistic, brief, practical training on the quality of CC-CPR performance in 2 convenience samples of citizens and health care professionals.

Previous studies have suggested the usefulness of short learning programs, similar to that of standard 4-hour courses, especially regard- ing skill retention. Sutton et al [36] found that low-dose, high-frequency bedside training improved pediatric CPR skill retention of hospital pro- viders. “Rolling refresher” CPR training based on repeated practical sim- ulation was also useful to achieve proficient CPR skills by the health care staff [37]. Regarding laypeople, brief educational videos have shown to significantly improve hands-only CPR skills among untrained adults, and also increase their willingness to act in a simulated scenario [25]. To our knowledge, no previous studies have analyzed whether an op- portunistic 5-minute practical training is able to improve citizens’ CPR performance and equal their results to those achieved by the health care professionals, who are expected to perform high-quality CPR [30]. Surprisingly, both groups surpassed the 70% goal for most of the technical parameters in the 2-minute test. Even if there was a trend to achieve slightly better results among the health care professionals, it was only statistically significant in 2 of the 8 quality metrics: total num- ber of compressions and mean compression rate. As mean CC rate stayed within the recommended range of 100-120 CC min-1 [30], it lacks real clinical relevance. Overall, quality of global performance assessed by the QCPR formula was also above the desirable objective

and showed no significant differences between samples.

Simple instructions, real-time feedback, and motivation to achieve successful results were the core elements of the tested strategy.

Fig. 2. Study flow diagram. Abbreviations: TCC, total number of CCs; MR, mean compression rate; CCAR%, percentage of CCs at adequate rate; MD, mean compression depth; CCAD%, per- centage of CCs at adequate depth; CCFR%, percentage of CCs with full-chest recoil; CCAH%, percentage of CCs with adequate hand position; QCPR%, global quality of hands-only CPR performance.

Contemporary studies have suggested the usefulness of real-time feed- back and motivation through competition and gamification to enhance acquisition and retention of CPR skills, among both health care staff [22,24,27] and laypeople [23]. Besides, a recent study including 87 un- trained youngsters has shown their ability to successfully perform CC- CPR on manikin by following dispatcher’s instructions, without a previ- ous training. In this line, our research suggests that untrained citizens are able to perform high-quality CC-CPR after an only 2-minute training. The low rates of bystander initiated CPR impel us to review CPR teaching methods and look for new approaches tailored to the real needs and circumstances of the population. Our research provides

Descriptive statistics for both samples: health care staff and laypeople

|

Mean (SD) |

P |

95% Confidence interval |

|

|

TCC Health care staff |

240.68 (30.44) |

.02 |

233.62-247.73 |

|

Laypeople |

229.31 (28.87) |

222.93-235.69 |

|

|

MR Health care staff |

119.07 (12.85) |

.006 |

116.09-122.05 |

|

Laypeople |

113.02 (13.90) |

109.95-116.10 |

|

|

CCAR% Health care staff |

55.97 (36.36) |

.43 |

47.55-64.40 |

|

Laypeople |

51.46 (35.32) |

43.65-59.27 |

|

|

MD Health care staff |

48.55 (6.76) |

.45 |

46.99-50.12 |

|

Laypeople |

47.58 (8.99) |

45.59-49.57 |

|

|

CCAD% Health care staff |

50.46 (37.17) |

.92 |

41.85-59.07 |

|

Laypeople |

49.88 (38.58) |

41.35-49.88 |

|

|

CCFR% Health care staff |

90.91 (18.84) |

.52 |

86.54-95.27 |

|

Laypeople |

92.77 (17.17) |

88.97-96.56 |

|

|

CCAH% Health care staff |

99.74 (1.98) |

.11 |

99.28-100.20 |

|

Laypeople |

96.94 (14.78) |

93.67-100.21 |

|

|

QCPR% Health care staff |

85.95 (14.48) |

.10 |

82.59-89.30 |

|

Laypeople |

81.23 (20.10) |

76.79-85.68 |

Abbreviations: as in Fig. 2.

further evidence that brief practical training may be an adequate strat- egy to teach laypeople, as it has shown to at least equal their skill acqui- sition to health care professionals. From our point of view, more initiatives as the above-mentioned would help to increase public awareness of the central role played by lay rescuers to improve the out- comes from OHCA, especially in public places where access to training could be readily available, such as hospitals, shopping malls, or airport terminal waiting areas. We consider that CPR learning should be acces- sible and naturally integrated into the citizens’ daily life to achieve the highest improvements, and in this regard, cardiac care professionals have an educational duty.

Our study has some limitations. Even if this training strategy succeed to improve untrained laypeople CC-CPR performance on a manikin, it is not possible to extrapolate these results to a situation of actual cardiac arrest, where confusion and stress play an important role. Previous studies have investigated the correlation between training and willing- ness to perform CPR, with variable results. Although previous training does not always translate into helping behavior [38], it has been sug- gested that activities that allow people to explore their fears make them more likely to act in actual emergencies [39]. Training may also modify their response by raising the rate of appropriate behavior pro- vided that they are motivated to help [40].

Although some Level of knowledge in CPR is expected from health care professionals, there is a lack of specific data on their prior training, as no formal CPR training protocol is established in our hospital. Regard- ing CPR metrics, we found that % of CC at adequate rate and also % of CC at adequate depth were only close to the 50% mark in both groups, even if the mean compression rate and mean depth showed satisfactory re- sults. There must have been a high variability in both components throughout the test probably due to fatigue, not accounted by the

Fig. 3. Hands-only CPR metrics error bar. Abbreviations: as in Fig. 2. A, Mean values for each of the CPR parameters are represented with their respective 95% confidence intervals. B, Global quality CPR performance was above the 70% goal, with no significant differences between both samples.

software when calculating the QCPR to evaluate the global performance, which may have been overestimated by the high scores of correct hand position and adequate chest recoil. Nevertheless, our study was not con- ceived to assess deterioration of CPR performance over the time during the test. Finally, according to the opportunistic character of the study, retention of skills in laypeople vs health care providers was not assessed. The next step would be to address the effectiveness of the brief practical training over time and to use it as a basis for “refreshing” skills, like it has been previously satisfactory described in health care populations [36,37].

After a very brief training supported by a real-time CC quality feed- back and hands-on instructor led advice, naive laypeople are able to perform good-quality hands-only CPR on a manikin. Simple instruc- tions, real-time feedback, and motivation might have been the key ele- ments of this training strategy, which could make feasible to train big numbers of citizens. We suggest that CPR training should be adjusted

to citizens’ real availability and circumstances. Selected initiatives, car- ried out in public places, may be a good opportunity to increase general awareness of the importance of bystander CPR to improve outcomes from OHCA.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no relationships that could be construed as a con-

flict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all collaborators among nursery students from Universidade de Santiago de Compostela involved in this study, as well as staff from the Cardiology Department and the Acute Care Unit, who helped to organize and carry out the project. Special mention should be made to instructors from the Faculty of Education and Sport Sciences from Universidade de Vigo for their contribution and material support.

- Priori SG, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: Association for Eu- ropean Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J 2015 Nov 1; 36(41):2793-867.

- Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular Disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representa- tives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012;33(13):1635-701.

- Sasson C, Rogers MAM, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of- hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3(1):63-81.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart Dis- ease and Stroke Statistics-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Associa- tion. Circulation 2015;131(4):e29-322.

- Grasner J-T, Bossaert L. Epidemiology and management of cardiac arrest: what reg- istries are revealing. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013;27(3):293-306.

- McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, Vellano K, Valderrama AL, Yoon PW, et al. Out-of-hos- pital cardiac arrest surveillance-Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005-December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60(8):1-19.

- Hasselqvist-Ax I, Riva G, Herlitz J, Rosenqvist M, Hollenberg J, Nordberg P, et al. Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(24):2307-15.

- Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, Weeke P, Hansen CM, Christensen EF, et al. Asso- ciation of national initiatives to improve Cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Med Assoc 2013;310(13):1377-84.

- Malta Hansen C, Kragholm K, Pearson DA, Tyson C, Monk L, Myers B, et al. Associa- tion of bystander and first-responder intervention with survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in North Carolina, 2010-2013. J Am Med Assoc 2015;314(3):255-64.

- Iwami T, Kitamura T, Kiyohara K, Kawamura T. Dissemination of chest compression- only cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2015;132(5):415-22.

- Holmberg M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Factors modifying the effect of bystander cardio- pulmonary resuscitation on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2001;22(6):511-9.

- Vaillancourt C, Grimshaw J, Brehaut JC, Osmond M, Charette ML, Wells GA, et al. A survey of attitudes and factors associated with successful cardiopulmonary resusci- tation (CPR) knowledge transfer in an older population most likely to witness cardi- ac arrest: design and methodology. BMC Emerg Med 2008;8:13.

- Greif R, Lockey AS, Conaghan P, Lippert A, De Vries W, Monsieurs KG, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015. Section 10. Education and implementation of resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015;95:288-301.

- Bhanji F, Donoghue AJ, Wolff MS, Flores GE, Halamek LP, Berman JM, et al. Part 14: Education 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2015;132(18 suppl. 2): S561-73.

- Waalewijn RA, Nijpels MA, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Prevention of deterioration of ven- tricular fibrillation by basic life support during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resus- citation 2002;54(1):31-6.

- Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, Stolz U, Sanders AB, Kern KB, et al. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac ar- rest. J Am Med Assoc 2010;304(13):1447-54.

- Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, Berg RA, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi T, et al. Effectiveness of bystander-initiated cardiac-only resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2007;116(25):2900-7.

- Bohm K, Rosenqvist M, Herlitz J, Hollenberg J, Svensson L. Survival is similar after standard treatment and chest compression only in out-of-hospital bystander cardio- pulmonary resuscitation. Circulation 2007;116(25):2908-12.

- Hallstrom A, Cobb L, Johnson E, Copass M. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by chest compression alone or with mouth- to-mouth ventilation. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(21):1546-53.

- Dumas F, Rea TD, Fahrenbruch C, Rosenqvist M, Faxen J, Svensson L, et al. Chest com- pression alone cardiopulmonary resuscitation is associated with better long-term survival compared with standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation 2013; 127(4):435-41.

- Wang J, Ma L, Lu Y-Q. Strategy analysis of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in the community. J Thorac Dis 2015 Jul;7(7):E160-5.

- Kirkbright S, Finn J, Tohira H, Bremner A, Jacobs I, Celenza A. Audiovisual feedback device use by health care professionals during CPR: a systematic review and meta- analysis of randomised and non-randomised trials. Resuscitation 2014 Apr;85(4): 460-71.

- Krasteva V, Jekova I, Didon J-P. An audiovisual Feedback device for compression depth, rate and complete chest recoil can improve the CPR performance of lay per- sons during self-training on a manikin. Physiol Meas 2011;32(6):687-99.

- Smart JR, Kranz K, Carmona F, Lindner TW, Newton A. Does real-time objective feed- back and competition improve performance and quality in manikin CPR training - a prospective observational study from several European EMS. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2015;23(1):79.

- Bobrow BJ, Vadeboncoeur TF, Spaite DW, Potts J, Denninghoff K, Chikani V, et al. The effectiveness of ultrabrief and brief educational videos for training lay responders in hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation implications for the future of citizen car- diopulmonary resuscitation training. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4(2): 220-6.

- Potts J, Lynch B. The American Heart Association CPR anytime program: the poten- tial impact of highly accessible training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Cardpulm Rehabil 2006;26(6):346-54.

- MacKinnon RJ, Stoeter R, Doherty C, Fullwood C, Cheng A, Nadkarni V, et al. Self- motivated learning with gamification improves infant CPR performance, a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn 2015 [bmjstel - 2015-000061].

- World Heart Day | World Heart Federation [Internet]. [cited 2015 Nov 22]. Available from http://www.world-heart-federation.org/what-we-do/world-heart-day.

- Georgiou M, Lockey AS. ERC initiatives to reduce the burden of cardiac arrest: the European Cardiac Arrest Awareness Day. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013; 27(3):307-15.

- Perkins GD, Handley AJ, Koster RW, Castren M, Smyth MA, Olasveengen T, et al. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2015. Section 2. Adult basic life support and Automated external defibrillation. Resuscitation 2015;95: 81-99.

- Oulego-Erroz I, Busto-Cuinas M, Garcia-Sanchez N, Rodriguez-Blanco S, Rodriguez- Nunez A. A popular song improves CPR compression rate and skill retention by schoolchildren: a manikin trial. Resuscitation 2011;82(4):499-500.

- Perkins GD, Colquhoun M, Simons R. Training manikins. In: Colquhoun M, Handley AJ, Evans TR, editors. In: ABC of Resuscitation. 5th ed. London: BMJ Publishing Books; 2004. p. 97-101.

- Hong DY, Park SO, Lee KR, Baek KJ, Shin DH. A different rescuer changing strategy between 30:2 cardiopulmonary resuscitation and hands-only cardiopulmonary re- suscitation that considers rescuer factors: a randomised cross-over simulation study with a time-dependent analysis. Resuscitation 2012;83(3):353-9.

- Wong MKY, Morrison LJ, Qiu F, Austin PC, Cheskes S, Dorian P, et al. Trends in short- and long-term survival among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients alive at hospi- tal arrival. Circulation 2014;130(21):1883-90.

- Lopez-de-Sa E, Lopez-Sendon J. Supervivientes a parada cardiaca antes de llegar al hospital. Mas alla de la reanimacion cardiopulmonar. Rev Esp Cardiol 2013;66(8): 606-8.

- Sutton RM, Niles D, Meaney PA, Aplenc R, French B, Abella BS, et al. Low-dose, high- frequency CPR training improves skill retention of in-hospital pediatric providers. Pediatrics 2011;128(1):e145-51.

- Niles D, Sutton RM, Donoghue A, Kalsi MS, Roberts K, Boyle L, et al. “Rolling re- freshers”: a novel approach to maintain CPR psychomotor skill competence. Resus- citation 2009;80(8):909-12.

- Swor R, Khan I, Domeier R, Honeycutt L, Chu K, Compton S. CPR training and CPR performance: do CPR-trained bystanders perform CPR? Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 2006 Jun;13(6):596-601.

- Oliver E, Cooper J, McKinney D. Can first aid training encourage individuals’ propen- sity to act in an emergency situation? A pilot study. Emerg Med J 2014;31(6):518-20.

- Shotland RL, Heinold WD. Bystander response to arterial bleeding: helping skills, the decision-making process, and differentiating the helping response. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985;49(2):347-56.