Atipamezole as an emergency treatment for overdose from highly concentrated alpha-2 agonists used in zoo and wildlife anesthesia

136 Correspondence / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 134-168

compared to anteroposterior (AP) and lateral ankle radiographs as well as AP and oblique foot radiographs. These sonographers were trained in a combined 4-hour practical and theoretical training session [16].

Within set of all foot fractures, Fifth metatarsal fracture identification with POCUS has been well documented. The vital importance of this is seen, as 5% of all fractures seen in the ED are metatarsal fractures, of which more than 50% involve the 5th metatarsal. After examining 5 test patients with fractures, ED physicians with no other formal training were able to detect 5th metatarsal fractures with a sensitivity of 97.1% and specificity of 100% by only observing for cortical disruption [17] (Table 1).

Sources of financial support

- Dallaudiere B, Larbi A, Lefere M, Perozziello A, Hauger O, Pommerie F, et al. Muscu- loskeletal injuries in a resource-constrained environment: comparing diagnostic ac- curacy of on-the-spot ultrasonography and conventional radiography for bone fracture screening during the Paris-Dakar rally raid. Acta Radiol Open 2015 May 27;4:2058460115577566.

- Carter K, Nesper A, Gharahbaghian L, Perera P. ultrasound detection of patellar frac- ture and evaluation of the knee extensor mechanism in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med 2016;17(6):814-6.

- Atilla OD, Yesilaras M, Kilic TY, Tur FC, Reisoglu A, Sever M, et al. The accuracy of bed- side ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for fractures in the ankle and foot. Acad Emerg Med 2014 Sep;21:1058-61.

- Yesilaras M, Aksay E, Atilla AD, Sever M, Kalenderer O. The accuracy of bedside ultra- sonography as a diagnostic tool for fifth metatarsal fractures. Am J Emerg Med 2014 Feb;32:171-4.

This study was not funded.

Author disclosure statement

No competing financial interests exist.

A. Pourmand MD, MPH*

H. Shokoohi MD, MPH

R. Maracheril, BS

Atipamezole as an emergency treatment for overdose from highly concentrated alpha-2 agonists used in zoo and wildlife anesthesia

The availability of highly concentrated forms of common Anesthetic agents has revolutionized zoo and wildlife medicine [1-3]. As an exam- ple, using highly concentrated alpha-2 agonists (?2a) such as medetomidine (MED), veterinarians are able to provide safe and effec-

Emergency Medicine Department, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, United States

*Corresponding author at: Department of Emergency Medicine, George Washington University, Medical Center, 2120 L St., Washington, DC

20037, United States.

E-mail address: [email protected] (A. Pourmand).

23 June 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.06.052

- National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Emergency department summa- ry tables. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_ tables.pdf; 2013. [accessed 10.05.17].

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and Economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005- 2025. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22(3):465-75.

- Kozaci N, Ay MO, Akcimen M, Turhan G, Sasmaz MI, Turhan S, et al. Evaluations of the effectiveness of bedside point-of-care ultrasound in the diagnosis and manage- ment of Distal radius fractures. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:67-71.

- Pourmand A, Lee D, Davis S, Dorwart K, Shokoohi H. Point-of-care ultrasound utili-

zations in the Emergency airway management: an evidence-based review. Am J Emerg Med 2017;35:1202-6 [pii: S0735-6757(17)30120-1].

- Avci M, Kozaci N, Beydilli I, Yilmaz F, Eden AO, Turhan S. The comparison of bedside point-of-care ultrasound and computed tomography in elbow injuries. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:2186-90.

- Ali AA, Solomon DM, Hoffman RJ. Femur fracture diagnosis and management aided by Point-of-care ultrasonography. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016;32:192-4.

- Marshburn TH, Legome E, Sargsyan A, Li SM, Noble VA, Dulchavsky SA, et al. Goal-di- rected ultrasound in the detection of Long-bone fractures. J Trauma 2004;57:329-32.

- Joshi N, Lira A, Mehta N, Paladino L, Sinert R. Diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, and bedside ultrasound for diagnosis of extremity fractures in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2013 Jan;20(1): 1-15.

- Rabiner JE, Khine H, Avner JR, Friedman LM, Tsung JW. Accuracy of point-of-care ul-

trasonography for diagnosis of elbow fractures in children. Ann Emerg Med 2013; 61:9-17.

arthrocentesis of the elbow: a posterior approach. J Emerg Med 2013;45:698-701.

- Aksay E, Yesilaras M, Kilic TY, Tur FC, Sever M, Kaya A. Sensitivity and specificity of bedside ultrasonography in the diagnosis of fractures of the fifth metacarpal. Emerg Med J 2015;32:221-5.

- Kozaci N, Ay MO, Akcimen M, Sasmaz I, Turhan G, Boz A. The effectiveness of bedside point-of-care ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of metacarpal frac- tures. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1468-72.

- Bozorgi F, Shayesteh Azar M, Montazer SH, Chabra A, Heidari SF, Khalilian A. Ability of ultrasonography in detection of different extremity bone fractures; a case series study. Emerg (Tehran) 2017;5(1):e15.

tive anesthesia of a 6000 kg elephant with a single 3-ml dart delivered from distances up to 50 m from the ground or by helicopter. Using these potent agents in the field, the potential for fatal accidents in humans is concerning because there is no antidote [1-4]. With highly concentrated medetomidine (HCMED), (40 mg/ml) an accidental dose of one milliliter is potentially 200 times an intravenous dose known to cause cardiac arrest in humans [5-8]. Life-threatening accidents with veterinary ?2a’s have been described in the literature [2,4].

The current management of accidental overdose (OD) of ?2a is primar- ily supportive care [9]. While not FDA approved for use in humans, atipamezole (AT) is a selective alpha-2 antagonist, which competitively in- hibits alpha-2 adrenergic receptors [10]. AT is routinely used in animals anesthetized with ?2a for the rapid reversal of sedation and analgesia [3]. AT has been studied in both unanesthetized and dexmedetomidine (DEX) sedated humans, and has been shown to be both safe and effective [10-11]. If a dart accident occurred with HcMED in a setting where there is no available intensive care, the results would be life-threatening. For veter- inarians and institutions using these dangerous drugs, an emergency pro- tocol using AT for resuscitation of an overdose of ?2a is badly needed [2]. We performed a PubMed search from 1970 to 2017 for all informa- tion related to AT use in humans [10-15]. We then compared the exper- imental AT dosing information obtained in human subjects with its use in primates and other animals to construct an algorithm for emergent

management of ?2a OD with AT.

Determination of a potential human AT reversal dose for use in emer- gencies requires an estimate of how much AT would be both safe and effec- tive using the known data from the human studies. Karhuvaara et al. studied the effect of AT in unanesthetized male volunteers at doses of up to 100 mg [10]. There were minimal side effects. Scheinin et al. studied human volun- teers exposed to 2.5 mcg/kg intramuscular DEX and then given 3 different doses of IV AT, one hour later. Only the 150 mcg/kg AT (AT/DEX ratio 60:1) fully reversed the sedative and Cardiovascular effects [13].

AT is routinely used at the end of a veterinary anesthetic on animals including primates, gorillas and chimpanzees, to reverse the ?2a for rapid recovery [3]. In Veterinary anesthesia AT is dosed on a milli- gram-to-milligram ratio relative to the amount of the ?2a used for an- esthesia. This reversal ratio is consistent in the veterinary literature, at approximately 5 times the MED dose [16-21].

The human trial data reveal that compared to animals including pri- mates, humans require approximately 10 times less ?2a such as DEX for deep sedation, and 10 times more AT for adequate reversal. It is also known that 100 mg AT is safe even in unanesthetized humans [10]. Using this information we have a devised a simple and practical

Correspondence / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 134-168 137

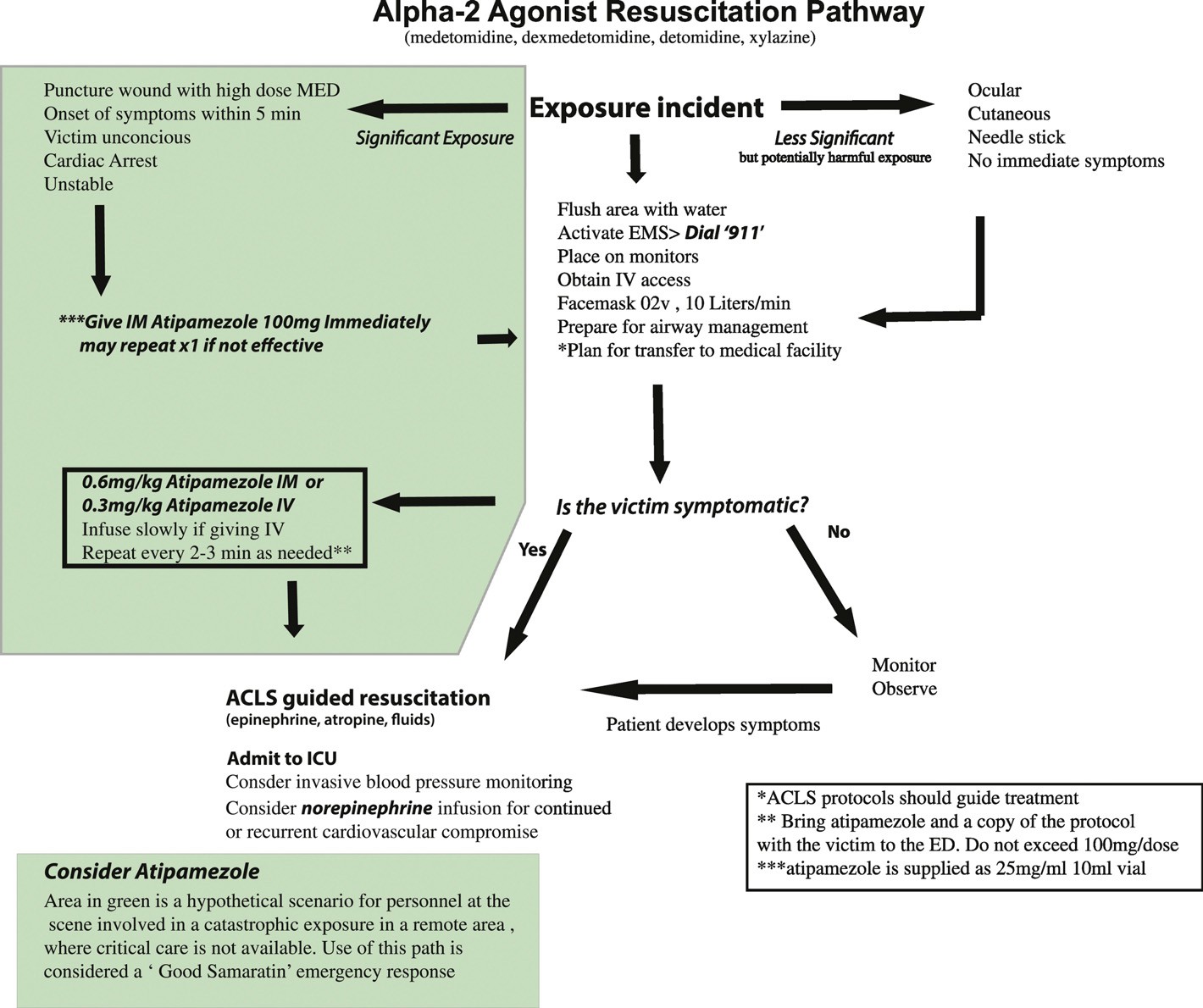

Fig. 1. Alpha-2 agonist overdose resuscitation pathway.

algorithm for using AT in a human ?2a OD emergency when other treatments are not available or are ineffective (Fig. 1).

For a significant ?2a exposure where medical aid is not available, the rescuers should consider immediately giving 100 mg AT intramuscu- larly. AT is supplied by one manufacturer in 25 mg/ml 10 ml vials, so a dose of 100 mg would be 4 ml. (Wildlife Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Windsor, CO 80550 USA) If the patient remains in critical condition after the first AT dose, the rescue team should consider a second dose. Individual doses of AT should not exceed 100 mg, due to lack of human data. If the victim is initially asymptomatic, we have devised a per-kilogram dose of AT to be used after the Initial resuscitation. At this point AT can be given when the patient develops symptoms, or for continued resuscitation of the initially 100 mg IM treated victim when Standard therapy fails. The rescuers should consider administer- ing 0.3 mg/kg IV or 0.6 mg/kg IM q 3-5 min, in repeated doses, (not to exceed 100 mg/dose), if needed, titrated to clinical effect. When the pa- tient is brought to a medical facility, a member of the veterinary team should accompany the patient, to provide essential information about the incident, and bring enough AT for potential use in the ED or ICU. A copy of the protocol in Fig. 1 would be helpful for the physicians caring for such a patient. It would also be helpful for veterinary teams working

with HcMED to proactively meet with the local emergency medicine physicians or poison control center and review this protocol. We urge considering using AT a non FDA approved drug, for life threatening ?2a OD in Remote locations where no other treatment is available.

Mark Greenberg, MD* Asheen Rama, MD

Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego, UCSD Medical Center, 200 West Arbor Dr, San Diego, CA 92103, USA

*Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (M. Greenberg),

[email protected] (A. Rama).

Jeffery R. Zuba, DVM Department of Veterinary Services, San Diego Zoo Safari Park, San Diego Zoo Global, 15500 San Pasqual Valley Rd, Escondido, CA 92027, USA

E-mail address: [email protected]

12 June 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.06.054

138 Correspondence / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 134-168

- Greenberg M, Zuba J, Rama A. Atipamezole as the Optimal treatment for alpha 2 ag- onist overdose. San Diego, California: American Society of Anesthesiologists; 26 Oct. 2015[Poster presentation].

- Haymerle A, Fahlman A, Walzer C. Human exposures to immobilizing agents: results of an online survey. Vet Rec [20120];167(9):327-32.

- Kreeger TJ. Handbook of wildlife chemical immobilization. International Wildlife Veterinary Services; 1996.

- Hoffmann U, Meister CM, Golle K, Zschiesche M. Severe intoxication with the veter- inary tranquilizer xylazine in humans. J Anal Toxicol 2001;25(4):245-9.

- Jorden VS, Pousman RM, Sanford MM, Thorborg PA, Hutchens MP.

Dexmedetomidine overdose in the perioperative setting. Ann Pharmacother 2004; 38(5):803-7.

- Bharati S, Pal A, Biswas C, Biswas R. Incidence of cardiac arrest increases with the in-

discriminate use of dexmedetomidine: a case series and review of published case re- ports. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwanica 2011;49(4):165-7.

- Ingersoll-weng E, Manecke G, Thistlethwait P. Dexmedetomidine and cardiac arrest. Anesthesiology 2004;100(3):738-9.

- Nagasaka Y, Machino A, Fujikake K, Kawamoto E, Wakamatsu M. Cardiac arrest in- duced by dexmedetomidine. Masui 2009;58(8):987-9.

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clonidine-and-related-imidazoline-poisoning.

[Kevin C Osterhoudt, MD, MS.] May 29, 2017

- Karhuvaara S, Kallio A, Scheinin M, Anttila M, Salonen JS, Scheinin H. Pharmacolog- ical effects and pharmacokinetics of atipamezole, a novel alpha 2-adrenoceptor an- tagonist-a randomized, double-blind cross-over study in healthy male volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1990;30(1):97-106.

- Karhuvaara S, Kallio A, Salonen M, Tuominen J, Scheinin M. Rapid reversal of alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist effects by atipamezole in human volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1991;31(2):160-5.

- Penttila J, Kaila T, Helminen A, et al. Effects of atipamezole-a selective alpha- adrenoceptor antagonist-on cardiac parasympathetic regulation in human subjects. Auton Autocoid Pharmacol 2004;24(3):69-75.

- Scheinin H, Aantaa R, Anttila M, Hakola P, Helminen A, Karhuvaara S. Reversal of the sedative and sympatholytic effects of dexmedetomidine with a specific alpha2- adrenoceptor antagonist atipamezole: a pharmacodynamic and kinetic study in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology 1998;89(3):574-84.

- Karhuvaara S, Kallio A, Koulu M, Scheinin H, Scheinin M. No involvement of alpha 2- adrenoceptors in the regulation of basal prolactin secretion in healthy men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1990;15(2):125-9.

- Mervaala E, Alhainen K, Helkala EL, et al. Electrophysiological and neuropsychologi- cal effects of a central alpha 2-antagonist atipamezole in healthy volunteers. Behav Brain Res 1993;55(1):85-91.

- Wenger S, Hoby S, Wyss F, Adami C, Wenker C. Anaesthesia with medetomidine, midazolam and ketamine in six gorillas after premedication with oral zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride. Vet Anaesth Analg 2013;40(2):176-80.

- Fahlman A, Bosi EJ, Nyman G. Reversible anesthesia of Southeast Asian primates with medetomidine, zolazepam, and tiletamine. J Zoo Wildl Med 2006;37(4):558-61.

- Bakker J, Uilenreef JJ, Pelt ER, Brok HP, Remarque EJ, Langermans JA. Comparison of three different sedative-anaesthetic protocols (ketamine, ketamine-medetomidine and alphaxalone) in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). BMC Vet Res 2013;9: 113.

- Reed F, Gregson R, Girling S, Pizzi R, Clutton RE. Anaesthesia of a captive, male giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Vet Anaesth Analg 2013;40(1):103-4.

- Lamberski N, Newell A, Radcliffe RW. Thirty immobilizations of captive Giraffe

(Giraffa camelopardalis) using a combination of medetomidine and ketamine. Amer- ican Association of Zoo Veterinarians; health and conservation of captive and free- ranging wildlife; 2006. p. 121-3.

- Cattet MR, Caulkett NA, Polischuk SC, Ramsay MA. Reversible immobilization of free- ranging polar bears with medetomidine-zolazepam-tiletamine and atipamezole. J Wildl Dis 1997;33(3):611-7.

Addressing the high rate of Opioid prescriptions for Dental pain in the

emergency department ?,??,???

Over two million people in the United States face an addiction to Prescription opioids and over twelve million reported abusing opioid medications in 2015 [1]. A common site of analgesic opioid prescription is for patients presenting with acute pain in the emergency department (ED). Approximately 50.3% of patients who present with non-traumatic dental pain in the ED receive a prescription for opioid drugs [2]. In con- trast, opioid analgesics were prescribed for just 14.8% of all other ED pa- tients [2]. Patients presenting with non-traumatic dental pain were also

? The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

?? No sources of support were provided, including in the form of equipment, drugs, or grants.

??? This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public,

commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

twice as likely to be prescribed an opioid drug over a non-opioid drug or no painkillers [2]. There were over 2.18 million visits to emergency de- partments for dental pain in 2012 alone, approximately 1.7% of total ED visits [3]. Additionally, Uninsured patients had the highest likelihood of receiving an opioid prescription (57.1%) [2]. Evidence suggests that opi- oid analgesic prescription by physicians in the emergency department may contribute to the development of long-term opioid use or addiction in some patients [4,5]. The high frequency of recurrent ED visits for acute dental pain [6] may be contributing to the increased availability of opioid drugs, addiction, and morbidity and mortality associated with prescription Opioid abuse. It’s imperative that emergency depart- ment physicians and researchers acknowledge this discrepancy in opi- oid prescription rates and consider non-traumatic dental pain as they develop and implement guidelines for safe prescribing of opioid analgesics.

For most patients presenting with non-traumatic dental pain, emer- gency department physicians provide antibiotics and analgesics to tem- porize the condition until a dentist can provide definitive treatment. The time consumed to evaluate and treat patients with dental pain may contribute to longer ED Waiting times and overcrowding, as well as take up time and space that could have been used for patients with more seri- ous, urgent conditions. The immense pressure on ED physicians to con- serve time and manage heavy patient loads isn’t frequently conducive to conducting thorough oral health examinations or reviewing prescrip- tion drug monitoring data.

We propose two workflow solutions to reduce the rate of opioid pre- scribing to patients presenting with non-traumatic dental pain in the emergency department. First, many emergency department physicians and staff have received training to administer bupivacaine dental blocks, local anesthesia injections that offer relief from dental pain for up to 11 h [7]. Encouraging physicians and nurses to utilize dental blocks more fre- quently may reduce the number of prescribed opioids. Additionally, we suggest that ED staff that have not received training in this simple proce- dure utilize publicly available online medical videos for self-training [8]. Second, evidence suggests that over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-in- flammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen alone may provide ef- fective analgesia for most non-traumatic dental pain and Dental procedures, including third molar extractions [9]. Research suggests that the use of controlled substance Prescribing guidelines that encourage the use of Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and dental nerve blocks before opioids for patients presenting with dental pain in the ED leads to a reduction in opioid analgesic prescription rates [10].

Emergency department treatment of non-traumatic dental pain may represent an important, possibly overlooked, area of high opioid prescrib- ing in the United States. As new approaches to curb opioid prescription rates, including novel guidelines and checklists to standardize best prac- tices, are implemented in health care organizations across the United States, it will be important to examine the incidence of opioid prescribing for dental conditions that present in medical settings.

Nisarg A. Patel, BS, BA

Harvard School of DentalMedicine, 188 Longwood Ave,

Boston, MA 02115, USA

E-mail address: [email protected]

Salim Afshar, DMD, MD

Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300

Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA Corresponding author at: Department of Plastic & Oral Surgery, 300 Longwood Avenue, Hunnewell, 1st Floor, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

E-mail address: [email protected]

3 May 2017