Comparison of SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS for the early identification of sepsis in the Emergency Department

a b s t r a c t

Objectives: The increasing use of sepsis screening in the Emergency Department (ED) and the Sepsis-3 recom- mendation to use the quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment necessitates validation. We com- pared Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome , qSOFA, and the National Early Warning Score for the identification of severe sepsis and septic shock (SS/SS) during ED triage.

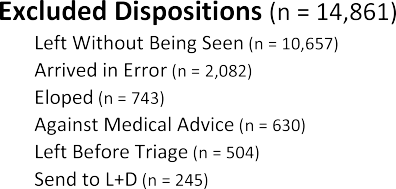

Methods: This was a retrospective analysis from an urban, tertiary-care academic center that included 130,595 adult visits to the ED, excluding dispositions lacking adequate clinical evaluation (n = 14,861, 11.4%). The SS/ SS group (n = 930) was selected using discharge diagnoses and chart review. We measured sensitivity, specific- ity, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) for the detection of sepsis endpoints.

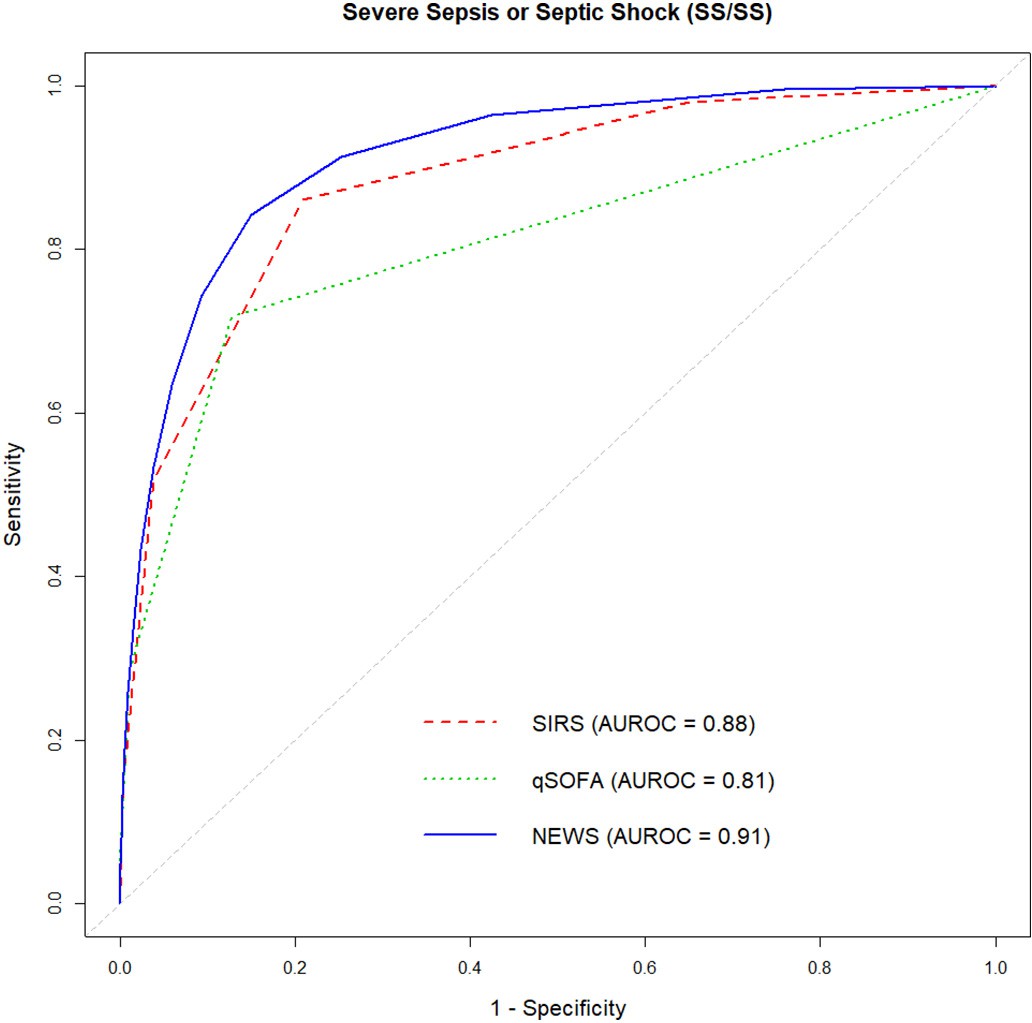

Results: NEWS was most accurate for triage detection of SS/SS (AUROC = 0.91, 0.88, 0.81), septic shock (AUROC = 0.93, 0.88, 0.84), and sepsis-related mortality (AUROC = 0.95, 0.89, 0.87) for NEWS, SIRS, and qSOFA, respec- tively (p b 0.01 for NEWS versus SIRS and qSOFA). For the detection of SS/SS (95% CI), sensitivities were 84.2% (81.5-86.5%), 86.1% (83.6-88.2%), and 28.5% (25.6-31.7%) and specificities were 85.0% (84.8-85.3%), 79.1%

(78.9-79.3%), and 98.9% (98.8-99.0%) for NEWS >= 4, SIRS >= 2, and qSOFA >= 2, respectively.

Conclusions: NEWS was the most accurate scoring system for the detection of all sepsis endpoints. Furthermore, NEWS was more specific with similar sensitivity relative to SIRS, improves with disease severity, and is immedi- ately available as it does not require laboratories. However, scoring NEWS is more involved and may be better suited for automated computation. QSOFA had the lowest sensitivity and is a poor tool for ED sepsis screening.

(C) 2018

Introduction

Background

Sepsis is a High-risk condition that carries considerable morbidity and mortality. There has been interest in the rapid detection of sepsis in the Emergency Department (ED) given the benefit of early interven- tion [1-3]. Early intervention is key for treating most life-threatening diseases, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiac arrest [4]. However, compared to these diseases, the diagnosis of sepsis is often more complex and lacks a rapid test, exam finding, or clinical decision tool that has emerged as a reliable predictor [2,3,5-11]. Furthermore,

Abbreviations: NEWS, National Early Warning Score; AVPU, Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive; AUROC, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve.

* Corresponding author at: 800 University Dr., Suite 310, Madison, WI 53705, United States of America.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (O.A. Usman), [email protected] (A.A. Usman), [email protected] (M.A. Ward).

there has been significant debate concerning the most appropriate method to evaluate sepsis in the ED [10,12-14].

The Sepsis-1 [15] and Sepsis-2 [5] guidelines established the defini- tion of sepsis and related conditions that many clinicians currently use in practice. However, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome has been criticized for its lack of specificity, prognostic value, and utility [11,16-18]. Due to these concerns, the recent Sepsis-3 guide- lines encourage the use of the quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assess- ment (qSOFA) when screening for sepsis [12]. Studies have shown that in non-ICU settings, qSOFA is a better predictor for mortality than SIRS [19-22].

Importance

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign [1] recommends the use of sepsis screening, which has been shown to reduce treatment time and im- prove outcomes [2,23,24]. Many severity scores have been developed to identify critically ill patients and EDs are turning to these tools to screen for sepsis. “Track and trigger” systems such as the National

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.058

0735-6757/(C) 2018

Early Warning Score (NEWS) have gained widespread adoption for detecting clinical deterioration for inpatients and are now being extended to the ED [25-29].

Goals of this investigation

The increased use of sepsis screening systems in the ED and the rec- ommendation to use qSOFA suggests the need for comparison and ex- ternal validation of these scoring systems [30-32]. The use of electronic medical records (EMR) and availability of large clinical data sets allows for comparison of different scoring systems. This study reviewed the viability of NEWS as an early predictor of severe sepsis and septic shock (SS/SS) in an ED triage setting and evaluated its perfor- mance against SIRS and qSOFA.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Chicago approved this study and consent was waived by the IRB.

Study design, setting, and eligibility

This was a retrospective data analysis from January 1, 2014 to April 30, 2015 and from February 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016. Data identi- fying positive sepsis cases were originally collected as part of a quality improvement initiative and were not available between these dates. We collected data from all adult patients (age >= 18 years) who pre- sented to the ED at an urban tertiary-care academic center with approx- imately 60,000 visits per year. This ED serves predominantly African- American patients, who constitute approximately 73% of all visits. We excluded dispositions that did not allow for full calculation of scores or adequate clinician evaluation (Fig. 1) and patients with a left ventric- ular assist device (unless their lactic acid was N2.0 mmol/L).

Data collection and quality control

All data were queried from a repository of records aggregated from the EMR (Epic Systems, Verona, WI). We gathered variables recorded at triage, including vitals, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and oxygen sup- plementation, in addition to demographics, leukocyte count, bands, dis- position, and in-hospital mortality. Physiologically impossible or implausible values were removed, which affected b1% of the data (see A. Data quality Control in the Online Supplementary Appendix).

Sepsis diagnosis

We evaluated our entire study population for the presence of SS/SS within 8 h of ED arrival. First, we selected all ED encounters with ICD- 9 (prior to October 1, 2015) or ICD-10 (on and after October 1, 2015) codes related to sepsis (see B. ICD Codes in the Online Supplementary Appendix). Next, to capture instances where there was Clinical concern for infection, we flagged patients with orders for blood cultures, urine cultures, or antibiotics within 12 h of ED arrival. Finally, an Emergency Medicine physician (MAW) reviewed each flagged chart using a stan- dardized process to determine whether suspected infection-related organ dysfunction occurred within 8 h of ED arrival. Given the subjectiv- ity in determining “suspected infection,” identified cases were con- firmed with the treating providers and a multidisciplinary quality improvement group to offer additional information and improve quality control. Data abstractors were blinded to input variables for sepsis scores and clinical endpoints. The physician chart reviewer was not blinded; however, cases were not originally identified for the purpose of this study and therefore, sepsis scores were not calculated or pre- sented to this reviewer.

Severe sepsis was defined as two or more SIRS criteria, concern for in- fection, and any of the following: lactic acid N 2.0 mmol/L, systolic blood pressure (SBP) b 90 mm Hg, MAP b 65 mm Hg, creatinine 0.5 mg/dL above baseline, INR N 1.5 (for patients not on anticoagulation), platelets b 100 x 109/L, or total bilirubin N 2 mg/dL (that was nota previous base- line) [5,15]. Septic shock was defined as having severe sepsis plus one of

Fig. 1. Study population, exclusions, inclusions, and endpoints. Shows included patients and associated dispositions, excluded patients and associated dispositions, and the severe sepsis and septic shock group with mortality rates. Patients were excluded if their stay was inadequate for clinical evaluation. Severe sepsis is defined per Sepsis-2 guidelines. Septic shock was defined as having severe sepsis plus one of the following: persistent hypotension (SBP b 90 mm Hg or MAP b 65 mm Hg) despite a one-liter crystalloid fluid challenge, lactic acid N3.9 mmol/L, or need for vasopressor within 8 h of ED arrival. All-cause in-hospital mortality included death during that visit’s hospitalization. ED = emergency department; L + D = labor and delivery; ICD = International Classification of Diseases.

the following: persistent hypotension (SBP b 90 mm Hg or MAP b 65 mm Hg)1 despite a one-liter crystalloid fluid challenge, lactic acid N 3.9 mmol/L, or need for vasopressor within 8 h of ED arrival [33].

Endpoints

Our primary endpoint was the diagnosis of severe sepsis inclusive of septic shock (SS/SS) within 8 h of ED arrival (as described above). Sec- ondary endpoints were severe sepsis, septic shock, and sepsis-related (in-hospital) mortality. The derivation of secondary endpoints can be found in C. Derivation of Secondary Endpoints in the Online Supplemen- tary Appendix.

Sepsis scoring systems

Our target measure was the ability for scoring systems to discrimi- nate patients with SS/SS. Three scoring systems were selected for statis- tical comparison: (1) SIRS [15], (2) qSOFA [12,19], and (3) NEWS [34,35] (Table 1). Previous studies have identified NEWS as high- performance, easily calculable in the ED, and useful for both inpatients and ED patients [27-29,35,36]. The Mortality in Emergency Department [9], Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [12], Multiple Organ Dysfunc- tion Score [15], Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II scores are included for comparison; however, these scoring systems were not viable as early predictors for sepsis in an ED triage setting due to the timing of their constituent variables.

We calculated scores using triage variables and, if present, the next available WBC and bands (see D. Calculation of Scoring Systems in the Online Supplementary Appendix). We conducted a complete case anal- ysis and 96.7% of the records allowed for calculation of all scoring sys- tems (we did not require lab values for the calculation of SIRS). SIRS includes PaCO2 measurement, but we did not collect data on this vari- able as arterial blood gases were rarely collected near the time of ED ar- rival [15].

The AVPU (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive) scale is required for the calculation of NEWS; however, our data only included GCS scores. We calculated an AVPU equivalent using GCS as described in E. Calculation of AVPU from GCS in the Online Supplementary Appendix.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted in R (R Foundation for Statistical Com- puting, 2017) [37] and the ROCR [38] and cvAUC [39] packages were used. We assessed Predictive ability using the area under the receiver- operating characteristic (AUROC) curves. Due to correlation between scoring systems, we employed the method described by Hanley and McNeil when comparing AUROCs [40,41]. A two-tailed p-value b 0.05 was required for statistical significance. Sensitivities and specificities are reported with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) using the Wilson Score interval. Baseline characteristics were compared using two- sample t-tests and chi-squared tests.

Results

Study population

We evaluated 130,595 ED visits comprising of 64,995 unique patients (Fig. 1). We excluded 11.4% dispositions (n = 14,861) with “Left without being seen” constituting 71.7% of all excluded cases (n = 10,657). Of the remaining 115,734 patients, 72.5% were discharged (n = 83,961) and 25.6% were admitted (n = 29,658). There were 930 cases of SS/SS (~8 cases per 1000 visits). There was an 11.5%, 17.6%, and 21.2% mortality

1 This definition matches the PROCESS trial but also included MAP b 65.

rate for severe sepsis exclusive of septic shock, SS/SS, and septic shock, respectively.

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 shows the SS/SS group had higher mortality (17.6 vs 0.6%), proportionally fewer women (50.8 vs 62.1%), required more supple- mental oxygen (55.4 vs 9.6%), and were older (63.0 [17.0] vs 46.5 [19.7] years) compared to all patients presenting to the ED, p b 0.001 for all comparisons.

Endpoint prediction

The AUROCs for the detection of SS/SS were SIRS = 0.88 (95% CI 0.867-0.897), qSOFA = 0.81 (95% CI 0.780-0.839), and NEWS = 0.91

(95% CI 0.903-0.926) (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Pairwise comparisons were then conducted between NEWS, SIRS, and qSOFA. For predicting SS/SS (Fig. 2), NEWS outperformed both SIRS (AUROC 0.91 vs 0.88, p b 0.001) and qSOFA (AUROC 0.91 vs 0.81, p b 0.001). Prediction results for our secondary endpoints of septic shock, sepsis-related mortality, and overall mortality is shown in F. ROC Curves for Secondary Endpoints in the Online Supplementary Appendix. For predicting septic shock, NEWS outperformed both SIRS (AUROC 0.93 vs 0.88, p b 0.001) and qSOFA (AUROC 0.93 vs 0.84, p b 0.001). For predicting sepsis-related mortality, NEWS outperformed both SIRS (AUROC 0.95 vs 0.89, p b 0.001) and qSOFA (AUROC 0.95 vs 0.87, p b 0.01). For predicting all- cause mortality, NEWS outperformed both SIRS (AUROC 0.88 vs 0.79, p b 0.001) and qSOFA (AUROC 0.88 vs 0.79, p b 0.001). SIRS

outperformed qSOFA in predicting SS/SS (Fig. 2, AUROC 0.88 vs 0.81, p b 0.001) and septic shock (AUROC 0.88 vs 0.84, p b 0.05), while there was no difference in the prediction of sepsis-related mortality (AUROC 0.89 vs 0.87, p N 0.1).

Test characteristics

Sensitivities and specificities for detecting sepsis endpoints are shown in Table 3. Previous studies have evaluated NEWS cutoffs of >=4 and >=8 for moderate and high-risk categories [27-29,36]. For the detec- tion of SS/SS, using a NEWS cutoff of >=8 provides a sensitivity of 43.3% (95% CI 39.9-46.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI 97.5%-97.7%).

For the detection of SS/SS, the positive predictive value (PPV) of SIRS

>= 2 is 3.3%, qSOFA >= 2 is 19.6%, NEWS >= 4 is 5.1%. For the detection of SS/SS, the negative predictive value (NPV) of SIRS >= 2 is 99.9%, qSOFA

>= 2 is 99.3%, NEWS >= 4 is 99.8%.

Based on our institution’s volume and sepsis prevalence, for the de- tection of SS/SS relative to NEWS (cutoff >=4), qSOFA (cutoff >=2) would have missed approximately 5 positive cases per week and SIRS (cutoff

>=2) would have inappropriately flagged approximately 9 cases per day.

Sepsis severity

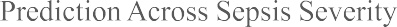

We report AUROCs across the spectrum of illness severity in Fig. 3 [15]. We found that qSOFA, while inferior in predicting less severe ill- ness, improves with illness severity. SIRS shows no sizeable improve- ment across severity. NEWS shows no statistically significant difference compared with SIRS in predicting severe sepsis exclusive of septic shock yet improves in predicting more severe illness and death. NEWS is superior to qSOFA in predicting outcomes across all illness severities.

Discussion

We found that NEWS is more accurate when compared with both SIRS and qSOFA for the early detection of SS/SS, septic shock, and sepsis-related mortality in an ED triage environment. SIRS is superior to qSOFA for prediction of SS/SS and septic shock alone but show no

Scoring systems’ characteristics and variables.

|

Population |

SS/SS AUROC |

Age |

Heart Rate |

Respiratory Rate |

Temperature |

Blood Pressure |

O2 Sat. / Supp. O2 / FiO2 |

Mental Status |

Medical History |

CBC / Differential |

Basic Metabolic Panel |

Liver Function Tests |

Urine Output |

Arterial Blood Gas |

Other Late Variables |

|||

|

SIRS |

Non-ICU |

Sepsis |

Diagnosis |

0.88 |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|||||||||

|

qSOFA |

Non-ICU |

Sepsis |

Screening |

0.81 |

? |

? |

? |

|||||||||||

|

NEWS |

Inpatient |

All |

Deterioration |

0.91 |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

||||||||

|

MEDS |

ED |

Sepsis |

Prognosis |

- |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

||||

|

SOFA |

ICU |

Sepsis |

Prognosis |

- |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

||||||

|

MODS |

ICU |

All |

Prognosis |

- |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|||||

|

APACHE II |

ICU |

All |

Prognosis |

- |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|||

|

ICU |

All |

Prognosis |

- |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

Increasing Clinical Time

- Required ? Optional / Alternative ? Not available at triage

Shows a list of scoring systems and their location, Disease states, and indications for which they were studied and intended for use. Clinical variables are listed from those immediately available to those requiring lab analysis or his- tory not routinely collected in the ED. AUROCs for determining severe sepsis and septic shock (SS/SS) are listed for those scoring systems considered usable in an ED triage setting. NEWS was determined to have the highest AUROC for SS/SS for the initial presentation to the ED compared with SIRS and qSOFA, p b 0.001. SIRS = Systemic Inflam- matory Response Syndrome, qSOFA = quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment, NEWS = National Early Warning System, MEDS = Mortality in Emergency Department, SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, MODS = Multiple organ dysfunction Score, APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SAPS II = Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; O2 Sat. = oxygen saturation; Supp. O2 = use of supplemental ox- ygen; FiO2 = fraction of inspire oxygen.

statistically significant difference for prediction of sepsis-related mor- tality. NEWS >= 4 is more specific and sensitivity is non-inferior com- pared with SIRS >= 2 for detection of SS/SS, septic shock, and sepsis-

Table 2

Baseline characteristics.

relate mortality. Additionally, NEWS is immediately available at triage as it does not require laboratories like SIRS. QSOFA’s low sensitivity compared to NEWS and qSOFA makes it a poor choice as a screening tool.

Scoring systems are tools that may heighten the clinical suspicion for sepsis and encourage physicians to perform time-critical interventions.

Included patients (n = 115,734)

Included patients (n = 115,734)

SS/SS

(n = 930)

p-Value

|

Age, mean (SD), years |

46.5 (19.7) |

63.0 (17.0) |

b0.001 |

|

Gender, no. (%) |

|||

|

Male |

43,808 (37.9) |

458 (49.2) |

b0.001 |

|

Female |

71,925 (62.1) |

472 (50.8) |

b0.001 |

|

Vital signs, mean (SD) |

|||

|

Heart rate, beats/min |

88.4 (17.7) |

112.0 (24.1) |

b0.001 |

|

Respiratory rate, breaths/min |

18.1 (2.6) |

21.5 (6.5) |

b0.001 |

|

Temperature, ?C |

36.3 (0.7) |

37.0 (1.5) |

b0.001 |

|

SBP, mm Hg |

132.6 (23.1) |

111.5 (27.9) |

b0.001 |

|

DBP, mm Hg |

77.8 (16.1) |

66.1 (22.0) |

b0.001 |

|

MAP, mm Hg |

94.1 (16.4) |

79.8 (21.8) |

b0.001 |

|

Oxygen saturation, % |

98.3 (2.6) |

95.6 (5.6) |

b0.001 |

|

Any supplemental oxygen, % |

9.6 |

55.4 |

b0.001 |

|

GCS, mean (SD) |

14.9 (0.8) |

13.5 (3.0) |

b0.001 |

|

Laboratory values, mean (SD) WBC, per mm3 |

8.8 (6.4) |

14.6 (10.3) |

b0.001 |

|

Bands, % |

N/Aa |

16.2 (13.3) |

|

|

Lactic acid (mmol/L) |

N/Aa |

3.5 (2.8) |

|

|

Disposition, no. (%) |

|||

|

Admitted |

29,657 (25.6) |

916 (98.5) |

b0.001 |

|

Expired in ED |

186 (0.2) |

10 (1.1) |

b0.001 |

|

In-hospital mortality |

730 (0.6) |

164 (17.6) |

b0.001 |

|

Scoring systems, mean (SD) SIRS |

0.9 (0.8) |

2.5 (1.0) |

b0.001 |

|

qSOFA |

0.1 (0.4) |

1.1 (0.9) |

b0.001 |

|

NEWS |

1.9 (2.0) |

7.1 (3.5) |

b0.001 |

Compares the baseline characteristics of all patient visits versus patients with ED-onset se- vere sepsis and septic shock. SS/SS = severe sepsis and septic shock, SD = standard devi- ation, ?C = degrees Celsius, SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, MAP = mean arterial pressure, mm Hg = millimeter of mercury, GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale, WBC = white blood cell count, mmol/L = millimole per liter, SIRS = Systemic In- flammatory Response Syndrome, qSOFA = quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assess- ment, NEWS = National Early Warning System.

a Not reported due to a large proportion of unobtained values.

Fig. 2. ROC curves for SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS. Shows receiver operating characteristic curves and associated area under the ROC (AUROC) for the detection of severe sepsis and septic shock (SS/SS) for SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS. SIRS = Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome; qSOFA = quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment; NEWS = National Early Warning System.

Sensitivities and Specificities for SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS

|

Cutoff >= |

SIRS |

|||||

|

SS/SS Septic Shock sepsis mortality |

||||||

|

Sen. |

Spec. |

Sen. |

Spec. |

Sen. |

Spec. |

|

|

1 |

98.0% |

34.9% |

97.8% |

34.8% |

98.1% |

34.7% |

|

2 |

86.1% |

79.1% |

87.1% |

78.9% |

88.6% |

78.7% |

|

3 |

51.8% |

96.1% |

53.7% |

96.0% |

55.7% |

95.8% |

|

4 |

15.1% |

99.6% |

15.8% |

99.5% |

18.4% |

99.5% |

|

Cutoff >= |

qSOFA |

|||||

|

SS/SS |

Septic Shock |

Sepsis Mortality |

||||

|

Sen. |

Spec. |

Sen. |

Spec. |

Sen. |

Spec. |

|

|

1 |

71.8% |

87.2% |

77.9% |

87.0% |

83.3% |

86.7% |

|

2 |

28.5% |

98.9% |

32.7% |

98.8% |

43.3% |

98.7% |

|

3 |

5.4% |

99.9% |

6.9% |

99.9% |

10.7% |

99.9% |

|

Cutoff >= |

NEWS |

|||||

|

SS/SS |

Septic Shock |

Sepsis Mortality |

||||

|

Sen. |

Spec. |

Sen. |

Spec. |

Sen. |

Spec. |

|

|

1 |

99.5% |

24.1% |

99.6% |

24.1% |

99.3% |

24.0% |

|

2 |

96.5% |

57.5% |

96.7% |

57.3% |

98.6% |

57.1% |

|

3 |

91.3% |

74.7% |

92.8% |

74.5% |

97.9% |

74.2% |

|

4 |

84.2% |

85.0% |

88.1% |

84.8% |

92.9% |

84.5% |

|

5 |

74.3% |

90.7% |

80.0% |

90.5% |

87.9% |

90.2% |

|

6 |

63.3% |

94.1% |

69.1% |

93.9% |

81.6% |

93.6% |

|

7 |

53.5% |

96.2% |

60.4% |

96.1% |

75.2% |

95.9% |

|

8 |

43.3% |

97.6% |

50.7% |

97.5% |

66.7% |

97.3% |

|

9 |

33.4% |

98.5% |

39.1% |

98.5% |

50.4% |

98.3% |

|

10 |

25.9% |

99.2% |

30.2% |

99.1% |

37.6% |

99.0% |

|

11 |

18.9% |

99.5% |

22.2% |

99.5% |

27.0% |

99.4% |

|

12 |

13.2% |

99.8% |

15.7% |

99.7% |

19.1% |

99.7% |

|

13 |

8.0% |

99.9% |

9.3% |

99.9% |

13.5% |

99.8% |

|

14 |

4.8% |

99.9% |

5.4% |

99.9% |

7.8% |

99.9% |

|

15 |

2.2% |

100.0% |

3.0% |

100.0% |

4.3% |

99.9% |

|

16 |

0.9% |

100.0% |

1.3% |

100.0% |

2.1% |

100.0% |

|

17 |

0.4% |

100.0% |

0.4% |

100.0% |

1.4% |

100.0% |

Shows sensitivity and specificity at different cutoff values for the detection of severe sepsis and septic shock (SS/SS), septic shock, and sepsis-related mortality for SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS. The highlighted SIRS >= 2 and qSOFA >= 2 cutoffs are part of the Sepsis-2 and -3 definitions, respectively. NEWS >= 4 and NEWS >= 8 are color- matched for similar sensitivity (teal) and specificity (yellow) to SIRS and qSOFA, re- spectively. SIRS = Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome; qSOFA = quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment; NEWS = National Early Warning System; Sen. = sensitivity; Spec. = specificity.

Therefore, scoring systems employed in the ED must have a low enough threshold to minimize missed sepsis cases [13,42]. Our results are con- sistent with previous studies that show qSOFA favors specificity over sensitivity [10,13,22,36,42,43]. One reason qSOFA may fail to achieve high sensitivity is due to omitting important physiologic variables (e.g. heart rate and temperature)-signals that often precede clinical deteri- oration [6,27]. Treatment may be delayed while waiting for organ dys- function to develop; and therefore, qSOFA may be better suited for later stage screening [13].

Both NEWS and SIRS provide better sensitivity for the detection of SS/SS in an ED triage setting compared with qSOFA (Table 3). To provide some perspective, for SS/SS in this study population, qSOFA would have missed almost five cases per week. NEWS provides superior specificity over SIRS without any significant difference in sensitivity. SIRS would inappropriately flag approximately 9 cases per day compared to NEWS. Further, prediction accuracy for NEWS is progressively better

with increasing severity of sepsis relative to SIRS (Fig. 3). Therefore, NEWS may be more useful in an ED triage setting compared with SIRS and qSOFA. However, SIRS and qSOFA were created as simple bedside Screening tools and are easier to calculate than NEWS [5,12]. Therefore, NEWS may best be implemented using automated EMR-based clinical tool calculators [9,19].

Churpek et al. conducted a similar study and found that early warn- ing scores are more accurate and provide an earlier response than qSOFA and SIRS for predicting mortality and ICU transfer for patients outside of the ICU with suspected infection [36]. We also found that table-based aggregate weighted systems, such as NEWS, were more predictive and robust compared with tally-based single parameter scores such as qSOFA and SIRS. This may be due to more cutoff points, bi-directional scoring (e.g. points for both hypothermia and fever) [11], and the ability to capture non-linear relationships.

NEWS may offer scoring flexibility relative to SIRS and qSOFA by allowing for the creation of multiple severity categories [11,27,28,35]. For example, the PPV for “low risk” patients (NEWS <= 3) was b3.3%, "moderate risk" patients (NEWS between 4 and 8) was 5.1-14.7%, and "high risk" patients (NEWS >= 9) was 17.8%-50%. Patients flagged as “moderate risk” may suggest obtaining a lactic acid, whereas patients flagged as “high risk” may benefit from the rapid mobilization of bun- dled resources and early ICU consultation [1,2].

Using AUROC as a measure, NEWS outperforms SIRS; this is likely due to the inclusion of mental status, blood pressure, and oxygenation, which are readily available indicators of end-organ dysfunction [10,35]. Another notable advantage of NEWS is that it has no reliance on laboratory values and is fully calculable at the time of triage. SIRS re- liance on laboratory values may delay the recognition and treatment of sepsis [2,29,44].

NEWS was developed for the detection of clinical deterioration in in- patients and not for the detection of sepsis in the ED and, therefore, not fully suited for the role to which it has been appropriated [45,46]. This is reflected in some of the NEWS components that may be inappropriate in the context of sepsis. We hypothesize that adjusting some of these variables or deriving a de novo sepsis scoring system may lead to im- provement [47,48].

In contrast to most studies, we calculated scores for unselected pa- tients versus only for those with suspicion for infection [9,10,19,21,22,36,42,43,48,49]. Additionally, we calculated scores using values available at the time of triage instead of using only the worst values over a period of time [19,21,22,36]. Our approach is more suit- able for screening at triage, when there is little information and the cli- nician has not evaluated the patient. We first ask, “what is the score?” and then ask, “based on this score, is there a concern for infection?” This was not the intended use of qSOFA, which first asks, “is there a con- cern for infection” and then asks “is the qSOFA >= 2?” [12,19] Our strategy carries a lower pretest probability and results in lower PPVs and higher NPVs compared with previous studies.

We limited our endpoints to manifestations of sepsis within 8 h of ED arrival, which differs from most other studies that do not hold this time constraint. This distinction resulted in higher sensitivities, specific- ities, and AUROCs for our study. It has been previously shown-and is in- tuitive-that predicting short-term events is easier and will increase overall accuracy [31,34]. A recent study by Keep et al. supports the ex- ternal validity of our results since they had similar patient and endpoint selection methods and showed comparable sensitivity of 92.6% versus 91.3% in our study and specificity of 77.0% versus 74.7% in our study for NEWS >= 3 [29].

Our reported mortality rate for SS/SS of 17.6% and septic shock of 21.2% was in line with other reports of between 12% and 30% for SS/SS and 18% and 46% for septic shock [2,3,6,8,9,18,20,21]. Our mortality AUROCs were generally larger than previously reported [21,22,31,42- 44,50-53]. This is due to our minimal inclusion criteria; studies that in- clude sicker patients have shown worse accuracy for mortality predic- tion [22,30,43].

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Sepsis prediction across disease severity. Shows area under receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve values versus the spectrum of illness severity for SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS. We found that qSOFA, while inferior in predicting less severe illness, improves with illness severity. SIRS shows no sizeable improvement across severity. NEWS shows no statistically significant difference compared with SIRS in predicting severe sepsis exclusive of septic shock, yet improves in predicting more severe illness and death, p b 0.001. NEWS is superior to qSOFA in predicting outcomes across all illness severities, p b 0.01. SIRS was non-inferior to qSOFA for sepsis-related mortality but outperforms qSOFA for severe sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock, and septic shock, p b 0.05. SIRS = Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome; qSOFA = quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment; NEWS = National Early Warning System.

We chose the diagnosis of SS/SS as our primary endpoint rather than mortality. Researchers have encouraged the validation of qSOFA and NEWS for outcomes other than mortality [19,22,35]. Many mortality- based scoring systems were created for risk stratification of inpatients and not for clinical decision-making in the ED [6,9,52,53]. Mortality pre- diction for sepsis in the ED was proposed by many during the era of early goal-directed therapy and drotrecogin-alfa in order to determine which patients should receive these aggressive and expensive treat- ments [4,7,9,53]. However, with the subsequent de-emphasis of these treatments, more importance is placed on the decision to treat sepsis. Once this decision has been made, prognostication may not significantly affect the ED mainstays of sepsis treatment: early antibiotics, source control, and cardiopulmonary optimization [1].

Limitations

Our study was retrospective, which may increase risk for misclassifi- cation biases and confounding. By calculating scores at triage, we dimin- ished the effect of confounding actions by clinicians. However, endpoint determination is still subject to reviewer bias as it was established retro- spectively and unblinded. Our findings may not apply to clinical areas outside of the ED as we limited our endpoints to manifestations within 8 h of presentation.

Our determination of severe sepsis is based on Sepsis-2 guidelines which may result in an incorporation bias favoring SIRS. However, Sepsis-2 organ-dysfunction is a subset of Sepsis-3 organ-dysfunction [10,12], mitigating this effect.

This is a single-center study with a predominately African-American population; multi-center inclusion would improve external validity. Given that most EDs routinely gather the inputs necessary for this anal- ysis, our study should be easily reproducible at other institutions.

Conclusions

From our retrospective analysis at one academic ED, we found that NEWS is more accurate than both SIRS and qSOFA for the early detection of SS/SS. Furthermore, NEWS is calculable at the time of triage, improves in prediction with increasing illness severity, and may better allow for risk stratification. While a handful studies have compared qSOFA with

SIRS for Mortality prediction, this is the first study to compare SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS for the early identification of sepsis in the ED.

All three of the scoring systems we analyzed showed the ability to identify sepsis. This result argues in favor of more EDs adopting sepsis screening systems, as recommended by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign [1]. Indeed, such systems have increasingly been incorporated into the triage process [52]. At our institution, we have adopted NEWS as an ini- tial screen for sepsis. We use a two-tier system: any score greater than six automatically flags the patient as potential severe sepsis and any score greater than three flags the patient as potential severe sepsis if deemed to be a high-risk for infection, including reported fever, history of immunocompromise, indwelling catheter, or triage nurse concern for infection.

We hope that this study will encourage other EDs to employ similar sepsis detection strategies by incorporating a scoring system that is eas- ily calculable, available at triage, and highly sensitive. In turn, these in- terventions may increase the emergency physician’s clinical suspicion for sepsis, reduce missed cases, and decrease the time to critical treatment.

Previous presentations

Presented at the “WACEP 2018 Spring Symposium & 26th Annual Wisconsin Emergency Medicine Research Forum” in Madison, WI on March 15th, 2018. Presented as a poster at the “Big Data in Precision Health Conference” at Stanford University in Stanford, CA on May 23rd, 2018.

Funding sources

Dr. Usman was supported in part by the Office of Academic Affilia- tions, Department of Veterans Affairs and the VA Health Services Re- search and Development (HSR&D) program through an Advanced Fellowship in Medical Informatics.

Conflict of interest disclosures

OAU reports no conflict of interest. AAU reports no conflict of inter- est. MAW reports no conflict of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Omar A. Usman: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Visual- ization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Asad A. Usman: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Michael A. Ward: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Super- vision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Usman was supported in part by the Office of Academic Affilia- tions, Department of Veterans Affairs and the VA Health Services Re- search and Development (HSR&D) program through an Advanced Fellowship in Medical Informatics. Views expressed are those of the au- thors and not necessarily those of the VA or other affiliated institutions. We would like to thank Mihai Giurcanu and David Liedke for their contributions.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.058.

References

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med 2017;45:486-552. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM. 0000000000002255.

- Funk D, Sebat F, Kumar A. A systems approach to the early recognition and rapid ad- ministration of best practice therapy in sepsis and septic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care 2009;15:301-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0b013e32832e3825.

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal- directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368-77.

- Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, Donnino M, Ngo L, Bates DW. Mortality in Emer- gency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score predicts 1-year mortality. Crit Care Med 2007;35:192-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000251508.12555.3E.

- Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:530-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x.

- Barriere SL, Lowry SF. An overview of mortality risk prediction in sepsis. Crit Care Med 1995;23:376-93.

- Crowe CA, Kulstad EB, Mistry CD, Kulstad CE. Comparison of severity of illness scor- ing systems in the prediction of hospital mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010;3:342-7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.70761.

- Macdonald SPJ, Arendts G, Fatovich DM, Brown SGA. Comparison of PIRO, SOFA, and MEDS scores for predicting mortality in Emergency Department patients with se- vere sepsis and septic shock. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1257-63. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/acem.12515.

- Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Moore RB, Smith E, Burdick E, Bates DW. Mortality in Emer- gency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score: a prospectively derived and validated clin- ical prediction rule. Crit Care Med 2003;31:670-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM. 0000054867.01688.D1.

- Williams JM, Greenslade JH, McKenzie JV, Chu K, Brown AFT, Lipman J. Systemic in- flammatory response syndrome, quick sequential Organ function assessment, and organ dysfunction: insights from a prospective database of ED patients with infec- tion. Chest 2017;151:586-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.057.

- McLymont N, Glover GW. Scoring systems for the characterization of sepsis and as- sociated outcomes. Ann Transl Med 2016;4. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2016.12. 53 (527-527).

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287.

- Simpson SQ. New Sepsis criteria: a change we should not make. Chest 2016;149: 1117-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.653.

- Vincent J-L, Martin GS, Levy MM. qSOFA does not replace SIRS in the definition of sepsis. Crit Care 2016;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1389-z.

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest 1992;101:1644-55. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.101.6.1644.

- Opal SM. The uncertain value of the definition for SIRS. Chest 1998;113:1442-3. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.113.6.1442.

- Vincent J-L. Sepsis definitions. Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:135. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S1473-3099(02)00232-3.

- Alberti C, Brun-Buisson C, Goodman SV, Guidici D, Granton J, Moreno R, et al. Influ- ence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis on outcome of

critically ill infected patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:77-84. https:// doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200208-785OC.

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A, et al. Assess- ment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:762-74. https://doi.org/10. 1001/jama.2016.0288.

- Donnelly JP, Safford MM, Shapiro NI, Baddley JW, Wang HE. Application of the third international consensus definitions for sepsis (Sepsis-3) classification: a retrospec- tive population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:661-70. https://doi. org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30117-2.

- Freund Y, Lemachatti N, Krastinova E, Van Laer M, Claessens Y-E, Avondo A, et al. Prognostic accuracy of Sepsis-3 criteria for in-hospital mortality among patients with suspected infection presenting to the Emergency Department. JAMA 2017; 317:301-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.20329.

- Finkelsztein EJ, Jones DS, Ma KC, Pabon MA, Delgado T, Nakahira K, et al. Comparison of qSOFA and SIRS for predicting adverse outcomes of patients with suspicion of sep- sis outside the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2017;21. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13054-017-1658-5.

- Hayden GE, Tuuri RE, Scott R, Losek JD, Blackshaw AM, Schoenling AJ, et al. Triage sepsis alert and sepsis protocol lower times to fluids and antibiotics in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.039.

- Jones SL, Ashton CM, Kiehne L, Gigliotti E, Bell-Gordon C, Disbot M, et al. Reductions in sepsis mortality and costs after design and implementation of a nurse-based early recognition and response program. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2015;41:483-91.

- Rees JE, Mann C. Use of the patient at risk scores in the emergency department: a preliminary study. Emerg Med J EMJ 2004;21:698-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj. 2003.006197.

- Subbe CP, Slater A, Menon D, Gemmell L. Validation of physiological scoring systems in the accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J EMJ 2006;23:841-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.035816.

- Corfield AR, Lees F, Zealley I, Houston G, Dickie S, Ward K, et al. Utility of a single early warning score in patients with sepsis in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2014;31:482-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-202186.

- de Groot B, Stolwijk F, Warmerdam M, Lucke JA, Singh GK, Abbas M, et al. The most commonly used disease severity scores are inappropriate for risk stratification of older emergency department sepsis patients: an observational multi-centre study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049- 017-0436-3.

- Keep JW, Messmer AS, Sladden R, Burrell N, Pinate R, Tunnicliff M, et al. National early warning score at Emergency Department triage may allow earlier identifica- tion of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective observational study. Emerg Med J 2016;33:37-41. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2014- 204465.

- Jones AE, Saak K, Kline JA. Performance of the mortality in emergency department Sepsis score for predicting hospital mortality among patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:689-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ajem.2008.01.009.

- Ghanem-Zoubi NO, Vardi M, Laor A, Weber G, Bitterman H. Assessment of disease- severity scoring systems for patients with sepsis in general internal medicine de- partments. Crit Care 2011;15:R95.

- Andaluz D, Ferrer R. SIRS, qSOFA, and organ failure for assessing sepsis at the emer- gency department. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:1459-62. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017. 05.36.

- ProCESS Investigators, Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT, Barnato AE, Weissfeld LA, et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1683-93. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1401602.

- Prytherch DR, Smith GB, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. ViEWS-towards a national early warning score for detecting adult inpatient deterioration. Resuscitation 2010; 81:932-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.014.

- The Royal College of Physicians. National early warning score : standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. London: The Royal College of Physicians; 2012.

- Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, Sokol S, Pettit N, Howell MD, et al. Quick sepsis- related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:906-11. https://doi.org/ 10.1164/rccm.201604-0854OC.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017.

- Sing T, Sander O, Beerenwinkel N, Lengauer T. ROCR: visualizing the performance of scoring classifiers. R package; 2015.

- LeDell E, Petersen M, van der Laan M. cvAUC: cross-validated area under the ROC

curve confidence intervals. R package; 2014.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982;143:29-36. https://doi.org/10.1148/ra- diology.143.1.7063747.

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983;148:839-43. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708.

- Askim A, Moser F, Gustad LT, Stene H, Gundersen M, Asvold BO, et al. Poor perfor- mance of quick-SOFA (qSOFA) score in predicting severe sepsis and mortality - a prospective study of patients admitted with infection to the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-017- 0399-4.

- April MD, Aguirre J, Tannenbaum LI, Moore T, Pingree A, Thaxton RE, et al. Sepsis clinical criteria in Emergency Department patients admitted to an intensive care

unit: an external validation study of quick sequential organ failure assessment. J Emerg Med 2017;52:622-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.10.012.

Talmor D, Jones AE, Rubinson L, Howell MD, Shapiro NI. Simple triage scoring system predicting death and the need for critical care resources for use during epidemics. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1251-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000262385. 95721.CC.

- Roland D, Coats TJ. An early warning? Universal Risk scoring in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J EMJ 2011;28:263. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2010.106104.

- Morgan RJM, Williams F, Wright MM. An early warning scoring system for detecting developing critical illness. Clin Intensive Care 1997;8:100.

- Cuthbertson BH, Smith GB. A warning on early-warning scores! Br J Anaesth 2007; 98:704-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aem121.

- Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. Review and performance eval- uation of aggregate weighted “track and trigger” systems. Resuscitation 2008;77: 170-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.12.004.

- Jaimes F, Garces J, Cuervo J, Ramirez F, Ramirez J, Vargas A, et al. The systemic inflam- matory response syndrome (SIRS) to identify infected patients in the emergency

room. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1368-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003- 1874-0.

Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, Gemmel L. Validation of a modified early warning score in medical admissions. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians 2001;94:521-6.

- Duckitt RW, Buxton-Thomas R, Walker J, Cheek E, Bewick V, Venn R, et al. Worthing physiological scoring system: derivation and validation of a physiological early- warning system for medical admissions. An observational, population-based single-centre study. Br J Anaesth 2007;98:769-74. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/ aem097.

- Olsson T, Terent A, Lind L. Rapid emergency medicine score: a new prognostic tool for in-hospital mortality in nonsurgical emergency department patients. J Intern Med 2004;255:579-87.

- Howell MD, Donnino MW, Talmor D, Clardy P, Ngo L, Shapiro NI. Performance of se- verity of illness scoring systems in Emergency Department patients with infection. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:709-14. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2007.02.036.