Sumatriptan for the treatment of undifferentiated primary headaches in the ED

Brief Reports

Sumatriptan for the treatment of undifferentiated primary headaches in the EDB

James R. Miner MD*, Stephen W. Smith MD, Johanna Moore, Michelle Biros MS, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN 55415, USA

Received 19 January 2006; revised 12 June 2006; accepted 26 June 2006

Abstract

Objective: In this study, we determine the effectiveness and adverse effects of sumatriptan when used in the emergency department (ED) as a First-line treatment for benign undifferentiated headaches, and determine if the International Headache Society (IHS) classification of migraine, probable migraine, or tension-type headache has any effect on the effectiveness of the treatment. We hypothesize that there is no difference in the effectiveness of pain relief or frequency and severity of adverse effects between patients with migraine, probable migraine, or tension-type headaches when treated with sumatriptan. Methods: This was a prospective observational study of adult ED patients undergoing treatment for primary headaches (ie, patients in whom head trauma, vascular disorders, infection, or disorders of facial or cranial structures have been clinically excluded). Other exclusions were Renal impairment, hepatic impairment, and risk factors for coronary artery disease. Consenting patients then were asked to complete a 100-mm Visual analog scale representing their perceived pain, after which they were interviewed by a research assistant who completed a headache diagnosis worksheet, which differentiates the headache by IHS criteria. The patient repeated the VAS score at 30 and 60 minutes. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and v2 tests.

Results: One hundred forty-seven patients were enrolled: 84 (57.1%) patients with migraine headache,

45 (30.7%) with a probable migraine headache, and 18 (12.2%) with a Tension headache. A 50%

reduction in VAS scores 60 minutes postdose was seen in 87 (59%) of 147 patients; 50 (60%) of 84

of migraine patients, 25 (56%) of 45 of probable migraine patients, and 12 (67%) of 18 tension patients ( P = .72). There were no serious adverse events reported. Forty-seven patients (32%) received Rescue medications after the 60-minute VAS score: 29 (34.5%) patients in the migraine group, 15 (33.3%) patients in the probable migraine group, and 3 (15.8%) patients in the tension-type headache group ( P = .26).

Conclusions: Most of the patients presenting with primary headaches had migraine or probable migraine headaches. There was no difference in sumatriptan’s effectiveness based on the classification of the headache using IHS criteria.

D 2007

This work was presented in part at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, May 2004, Orlando, Fla, and at the American Headache Society Research Assembly, June 2004, Vancouver, BC.

B This work was supported in part by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 612 873 8791.

E-mail address: [email protected] (J.R. Miner).

0735-6757/$ – see front matter D 2007 doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2006.06.004

Introduction

There are many taxonomies of headache. Primary head- aches, also known as benign headache, are the headaches that are not bsecondaryQ to some identified discrete pathology (eg, meningitis, sinusitis, subarachnoid hemor- rhage, and toothache). Headaches present a frequent diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to emergency physi- cians. In fact, it is estimated that patients with the complaint of headache account for 1% to 2% of all emergency department (ED) visits [1]. Very little is known about the

differences in etiology and treatment of the primary head- aches. The International Headache Society (IHS) has established several definitions for classifications of head- aches [1]. Although these remain useful in determining Long-term treatment strategies, most ED patients present with undifferentiated headaches [2]. These include mi- graine, probable migraine, episodic tension-type, and Cluster headaches. The benign causes of headache (primary head- aches) have been reported to account for up to 90% of ambulatory patients presenting with a complaint of head- ache [3].

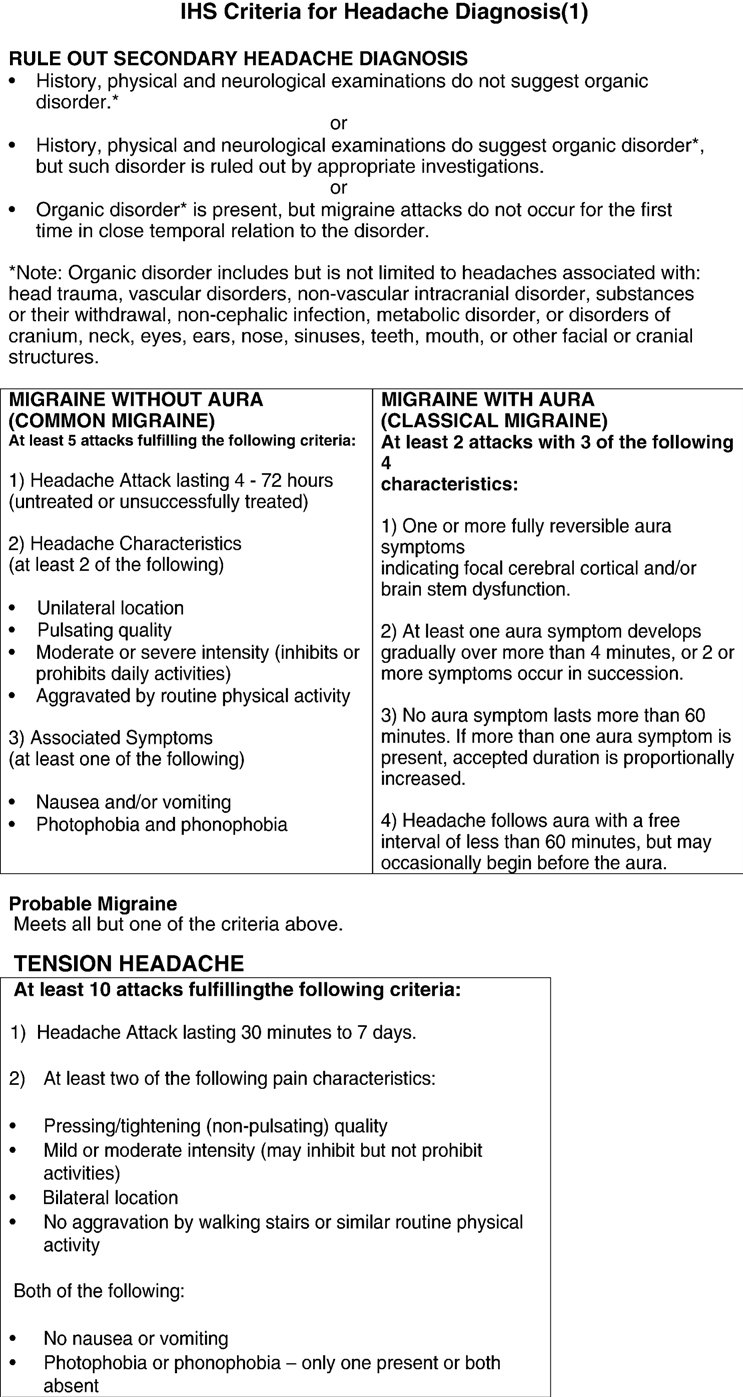

Fig. 1 Headache diagnosis worksheet.

Sumatriptan has been shown to be effective in treating the spectrum of Primary headache subtypes in clinic patients [3]. Its adverse effects include coronary artery spasm and chest pain, but these occur rarely. Although it has been established that sumatriptan is an effective treatment for migraine headaches, it is unknown whether it is effective in ED patients for primary headaches of the subtypes other than migraine. It is difficult to formally establish the diagnosis of migraine headaches in ED patients because it generally requires 5 episodes for the diagnosis to be made. The objective of this pilot study was to determine the effectiveness of sumatriptan when used in the ED as a first- line treatment for undifferentiated primary headaches and to determine if the IHS classification as migraine, probable migraine, or tension type has any effect on the outcome.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective observational study of adult ED patients undergoing treatment for primary headaches. The institutional review board of the Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minn, approved the study.

Study setting and population

This study was performed at the Hennepin County Medical Center, an urban county hospital with approxi- mately 93000 ED patient visits per year between January 30, 2003, and September 30, 2004. A convenience sample of adult (older than 18 years) ED patients who were going to be treated for a primary headache were included (ie, patients in whom head trauma, vascular disorders, infection, or disorders of facial or cranial structures have been clinically excluded). Exclusion criteria included prior use of triptans or ergots for this headache, renal or hepatic impairment, MAO-I use at present or in the past, a history of vascular disease, pregnancy or breast-feeding, or having at least 1 of the following coronary artery disease risk factors: hyper- tension, hypercholesterolemia, tobacco abuse, obesity,

diabetes, a family history of coronary artery disease, males older than 40 years, or postmenopausal females.

Study protocol

Consenting patients were asked to complete a visual analog scale representing their perceived pain. This scale was a 100-mm line with the words bno painQ on 1 end and bmost pain imaginableQ on the other. Patients were then treated with sumatriptan 6 mg subcutaneously and inter- viewed by a trained research assistant who completed a headache diagnosis worksheet, which differentiates the headache by IHS criteria (Fig. 1). Patients were asked to repeat the VAS 30 and 60 minutes after receiving the drug. Pain relief was defined as a 50% decrease in the pain VAS score. The patient’s physician was asked to report any adverse effects of the medication. Patients were contacted by telephone 48 hours after enrollment and queried regarding continuing pain and the need for further treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected by a designated research assistant and was then entered into an EXCEL (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash) database. All analysis and interpretation of data were performed using STATA 6.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, Tex) statistical software.

Descriptive statistics were used when appropriate. The rates of patients achieving a 50% reduction in their pain VAS score by headache classification and other nonpara- metric parameters of the study groups were compared using v2 tests.

To find an effect size of 0.3 in a v2 table comparing 50% pain relief in the 3 groups, with an a of .10 and 90% power,

we estimated that it was necessary to enroll 146 patients in the study.

Results

One hundred sixty-seven patients were enrolled (mean age, 28.4 F 14.4; 74% female). Fifteen patients did not

|

Table 1 Outcomes of the study |

||||

|

Migraine |

Probable migraine |

Tension |

Total |

|

|

87.7 (83.1-92.3) |

75.4 (66.9-83.8) |

77.4 (60.7-94.1) |

82.3 (78.5-86.9) |

|

|

Available for follow-up |

58 (66.7%) |

30 (65.2%) |

7 (36.8%) |

95 (62.5%) |

|

Minutes in the department |

51.2 F 105.1 |

107.8 F 155.6 |

90.2 F 177.5 |

72.9 F 133.9 |

|

(range, 15-730) |

(range, 20-730) |

(range, 25-720) |

(range, 15-730) |

|

|

% decrease in VAS score |

34.7 (26.7-42.8) |

19.5 (–12.8 to 51.8) |

38.3 (9.1-67.5) |

30.5 (19.3-41.7) |

|

at 30 min (95% CI) |

||||

|

% decrease in VAS score |

56.5 (48.2-61.8) |

42.1 (17.4-66.9) |

60.4 (38.4-82.4) |

52.6 (43.4-61.8) |

|

at 60 min (95% CI) |

||||

|

50% decrease in VAS at 30 min |

41 (49%) |

20 (44%) |

12 (67%) |

73 (50%) |

|

50% decrease in VAS at 60 min |

50 (60%) |

25 (56%) |

12 (67%) |

87 (59%) |

|

CI indicates confidence interval. |

||||

consent to be in the study. Four patients who gave consent left the department before being discharged and did not give a 30-minute VAS score (1 tension, 1 probable migraine, and 2 migraines). One patient was given a rescue medication before the 30-minute VAS score and was excluded (migraine group). One patient was eventually diagnosed with viral meningitis and excluded from the study. This left 146 patients with data appropriate for analysis.

Using IHS criteria, 84 (57.1%) patients presented with a migraine headache, 45 (30.7%) with a probable migraine headache, and 18 (12.2%) with a tension headache. There was no difference in the age ( P = .64) or sex ( P = .85) of the 3 groups. Fifty-nine patients reported having a previous headache diagnosis from a physician; they included 24 pa- tients with migraine, 3 with cluster, 7 with tension, 18 who had unspecified diagnoses, and 7 with posttraumatic conditions. There was no difference in the distribution of these previous diagnoses between the 3 groups ( P = .82).

The outcome parameters are presented in Table 1. Fifty- four (65%) of 83 patients with a history of migraine headaches had a 50% decrease in their VAS score at 60 minutes compared with 39 (61%) of 64 without a history of migraines ( P = .61). There was no difference between Headache types in terms of the measured pain relief by the VAS scales.

Thirty-six adverse events were noted. Seven patients reported increased drowsiness, 7 reported worsening head- ache, 6 reported nausea, and 2 reported shortness of breath. Thirteen patients reported chest and neck burning or tightness, all for less than 60 minutes. All of these patients had an electrocardiogram performed, and none of these patients were noted to have abnormalities after experiencing these symptoms. One patient developed a fever 45 minutes after the administration of sumatriptan and went on to be diagnosed with viral meningitis. This person did not have relief of their headache pain from the sumatriptan.

Forty-seven patients (32.0%) received rescue medica- tions after the 60-minute VAS score: 30 (20.4%) patients received droperidol, 11 (7.5%) received oral hydrocodone/ acetaminophen, 5 (3.4%) received parenteral morphine, and 1 (0.6%) received lorazepam. There was no difference in the type of rescue medications given between headache-type groups ( P = .77). Rescue medications were given to

29 (34.5%) patients in the migraine group, 15 (33.3%) patients in the probable migraine group, and 3 (16.7%) patients in the tension-type headache group ( P = .26).

Ninety-five (64.6%) patients were available for follow- up at 48 hours. Sixty-three (66.3%) of these patients reported continuing headache symptoms: 40 (63.5%) patients in the migraine group, 19 (30.2%) in the probable migraine group, and 4 (6.3%) in the tension group ( P = .85). Thirty-one patients (49.2%) described the continuing head- aches as light, 6 (9.5%) as moderate, and 26 (41.3%) as severe. There was no difference in the description of the severity of pain between the 3 groups ( P = .95). Fourteen patients (14.7%) had sought further treatment for their

headaches. No further adverse effects from those noted before discharge were found in the follow-up calls.

Discussion

Sumatriptan has been well described in the treatment of acute migraine headaches outside of the ED [1,4,5]. It is not known, however, if patients presenting to the ED with primary headaches will respond to a medicine indicated only for migraine headaches. Most of the patients enrolled in this study had either a migraine or a probable migraine headache. Tension headaches represented only a small portion of the patients who qualified for our study. The distribution of headache subtypes identified here is similar to previous reports of primary headache distributions [3], but the rate of migraine, migrainous, and tension headaches among patients presenting to the ED and requiring a pain medication has not been well described, and we cannot comment on whether or not this is unique to our institution. The adverse events noted were similar in nature and frequency to previous reports for sumatriptan [6]. We used a large number of exclusion criteria, including patients with cardiac risk factors, which may have prevented possible adverse events. We assume that the rate of adverse events from sumatriptan would be much higher among such patients with cardiac risk factors such as hypertension,

obesity, or Tobacco use.

We found very few differences between patients with migraines, probable migraine, or tension-type headaches in this study. The differentiation of headaches among migraine, probable migraine, and episodic tension type does not appear to be associated with the effectiveness of sumatriptan, and its effectiveness in all groups was similar to previous reports for migraine headache treatments in the ED [2,7-9]. It is possible that the IHS criteria do not offer a useful differentiation for the treatment of headaches in the ED.

Limitations

This study’s primary limitation is that it is not a randomized comparison of treatments. We felt that to establish the importance of the differentiation of primary headache subtypes on headache treatment in the ED, we should first compare the effectiveness of a known treatment for migraine headaches to other primary headache subtypes (probable migraine and episodic tension-type headaches) because it is not yet established if different subtypes of primary headaches in the ED will respond similarly to pain treatments.

A further limitation was that only patients with no cardiac risk factors were enrolled. This is not typical of a sample of a population of ED patients and limits the extrapolation of the findings here to patients without cardiac risk factors.

The distribution of headaches in our study was heavily weighted toward migraine headaches, with only a small number of patients classified as having a tension headache. It is not clear if this is an anomaly of our study population or is indicative of general ED patients who require pain medications for a primary headache. A large study of all patients presenting with primary headache will be needed to determine the prevalence of each head- ache subtype.

Conclusion

Most primary headaches in this study were classified as migraine or probably migraine. There was no difference in sumatriptan’s effectiveness for primary headaches based on the classification of the headache using IHS criteria. Sumatriptan’s effectiveness in this sample of undifferen- tiated primary headaches in the ED was similar to pre- vious reports.

References

- IHC Committee. ICD-10 guide for headaches. Cephalalgia 1997; 17(Suppl 19):1 – 82.

- Morgenstern LB, Huber JC, Luna-Gonzales H, et al. Headache in the emergency department. Headache 2001;41(6):537 – 41.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Cady R, et al. Sumatriptan for the range of headaches in migraine sufferers: results of the spectrum study. Headache 2000;40(10):783 – 91.

- Dowson AJ, Lipscombe S, Sender J, Rees T, Watson D. New guidelines for the management of migraine in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin 2002;18(7):414 – 39.

- Silberstein SD. Evaluation and emergency treatment of headache. Headache 1992;32(8):396 – 407.

- Silberstein SD, Rosenberg J. multispecialty consensus on diagnosis and treatment of headache. Neurology 2000;54(8):1553.

- Miner JR, Fish SJ, Smith SW, Biros MH. Droperidol vs. prochlorper- azine for benign headaches in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8(9):873 – 9.

- Richman PB, Reischel U, Ostrow A, et al. Droperidol for Acute migraine headache. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17(4):398 – 400.

- Diamond ML. Emergency department management of the acute headache. Clin Cornerstone 1999;1(6):45 – 54.