Association between focused cardiac ultrasound and time to furosemide administration in acute heart failure

a b s t r a c t

Background: heart failure is a global health burden, and its management in the emergency department (ED) is important. This study aimed to evaluate the association between Focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS) and early administration of diuretics in patients with acute HF admitted to the ED.

Methods: This retrospective observational study was conducted at a tertiary academic hospital. Patients with acute HF patients who were admitted to the ED and receiving intravenous medication between January 2018 and December 2019 were enrolled. The main exposure was a FoCUS examination performed within 2 h of ED triage. The primary outcome was the time to furosemide administration.

Results: Of 1154 patients with acute HF, 787 were included in the study, with 116 of them having undergone FoCUS. The time to furosemide was significantly shorter in the FoCUS group (median time (q1-q3), 112 min; range, 65-163 min) compared to the non-FoCUS group (median time, 131 min; range, 71-229 min). In the multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, chief complaint, mode of arrival, triage level, shock status, and desaturation at triage, early administration of furosemide within 2 h from triage was signifi- cantly higher in the FoCUS group (adjusted odds ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence intervals, 1.04-2.55) than in the non-FoCUS group.

Conclusions: Early administration of intravenous furosemide was associated with FoCUS examination in patients with acute HF admitted to the ED. An early screening protocol could be useful for improving levels in clinical practice at EDs.

(C) 2022

heart failure is a global Public health concern that affects approximately 26 million people and has a high burden of healthcare expenditure worldwide [1-3]. The prevalence of HF has increased with age, and it is the most common disease for hospitalization of older indi- viduals over the age of 65 in the United States [4-6]. Patients hospital- ized with HF show high in-hospital and post-discharge mortality rates and a high rehospitalization rate [7,8]. Assessment and management in the emergency department (ED) are important, as admission for acute HF has been increasing [9,10].

Management of acute HF, including specific laboratory tests or administration of vasopressors, has been demonstrated to be

E-mail address: [email protected] (K.H. Kim).

time-sensitive [11-13]. Diuretics, which are the initial treatment of choice for acute HF with volume overload, have also been associated with better survival outcomes if administered early [14]. A recent study indicated that myocardial damage can occur in the acute phase of HF and that early treatment may be helpful [15]. Accordingly, recent guidelines for HF recommend that physicians assess and provide immediate treatment [16,17].

Point-of-care ultrasound has been an important tool in the ED setting because it can help in rapid and accurate diagnosis without the risk of radiation [18-22]. Point-of-care Cardiopulmonary ultrasound has been found to increase the proportion of appropriate management for respiratory failure in a recent trial [23]. focused cardiac ultrasound has been recommended as an important tool for assessing patients with signs and symptoms of HF in the ED [24,25].

The time-saving effect of FoCUS in the treatment and disposition of acute HF has not been well studied. We hypothesized that early FoCUS

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.07.020

0735-6757/(C) 2022

evaluation in patients with suspected acute HF would provide insight into immediate management plans for emergency physicians. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between FoCUS and early administration of intravenous furosemide in patients with acute HF admitted to the ED.

- Methods

- Study design and setting

A retrospective observational study based on the point-of-care ultra- sound registry in a tertiary academic teaching hospital located in a met- ropolitan city and being visited by approximately 70,000 patients annually was performed. Emergency physicians routinely assess patients with symptoms or signs of HF based on history, physical exam- ination, and electrocardiography. If physicians decide to assess heart function immediately, FoCUS will be performed. It can be performed by physicians themselves or emergency medicine residents who are on duty in a point-of-care ultrasound rotation schedule [26]. Formal echocardiography or chest computed tomography can be performed but often requires a few hours of waiting. Otherwise, routine blood tests with cardiac biomarkers can be performed, which usually take at least 2 h. After assessment, physicians order proper medical manage- ment for HF and consult cardiologists for admission. Delays in treatment or disposition are strongly prohibited according to the operation protocol of the ED because of High demands.

-

- Data source

The point-of-care ultrasound registry was recorded by the physician who conducted the ultrasound. It contains demographic information about the patients and the time of examination. We also retrieved clinical information from the ED administrative database. The two data- bases were merged based on the patient number and ED visit time. A medical record review for detailed clinical information, including time to treatment or time to consultation, was conducted by research coordinators blinded to whether FoCUS was performed.

Patients with acute HF who visited an adult ED and were admitted between January 2018 and December 2019 were enrolled in the study. The diagnosis of acute HF was defined as a case in which the main diagnosis was recorded by a physician as “heart failure” or “acute pulmonary edema” in the ED administrative database (ICD-10 codes of I50.x or J81.0). Patients who were discharged from the ED, died in the ED, transferred from or to another hospital, or were not administered intravenous medication within 24 h were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome was the time to furosemide administration, which is the elapsed time interval between triage at the ED and place- ment of intravenous (IV) furosemide. The secondary outcome was the time to any IV medication, including furosemide, nitroglycerin, and inotropes. The tertiary outcome was the time to disposition between triage at the ED and consultation with an on-call cardiologist for admis- sion. All outcomes were measured through a medical record review with nursing records and consultation notes.

The main exposure for this study was the FoCUS examination for the screening of heart function. The components of the examination were not strictly limited, but any point-of-care ultrasound of the heart

assessing systolic dysfunction and evidence of hypervolemic status, such as pleural effusion or plethora of Inferior vena cava , was considered appropriate. Using the point-of-care ultrasound registry, we calculated the time interval from triage at the ED to FoCUS examina- tion for each study participant. FoCUS was defined as appropriate if the examination was conducted within 2 h of triage at the ED, considering the effect of early assessment, which could bring changes in practice. In the study hospital, the time from triage to physician evaluation was shorter than 30 min, and reporting the initial laboratory test with chest radiography took 2-3 h from triage.

Demographic findings and outcomes were collected: age, sex, chief complaint (chest pain, dyspnea, or other), method of entry (private am- bulance, emergency medical service, or other), physiologic status at ED triage (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, body temperature, and Pulse oximeter), ED triage, routine laboratory tests (hemoglobin, estimated glomerular filtration rate, serum sodium, high-sensitivity tro- ponin I, and brain natriuretic peptide), additional imaging test for HF (chest computed tomography, echocardiography), IV medication ad- ministration (IV furosemide, IV nitroglycerin, IV inotropes), Cardiologist consultation for admission, length of stay in the ED, and intensive care unit admission. In South Korea, the triage level of ED is divided into five levels based on the needs of medical resources: immediate resusci- tation, very urgent, urgent, standard, and non-urgent level [27].

-

- Statistical analyses

A descriptive analysis was conducted on the demographics and characteristics of the participants. Times to furosemide, IV medications, and disposition were compared using the Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for each group. An additional multivariate logistic regres- sion analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between FoCUS and early treatment. Early IV diuretics, IV medications, and consultation for disposition were defined as practices within 2 h of triage because they could be cutoff values from the administration of treatment after routine assessment, including blood tests. We selected confounders, such as the age (<=65, 66-85, and >85years), sex, chief complaint, mode of arrival (ambulance or not), shock status at triage (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), desaturation at triage (pulse oximetry

<90%), and triage level (immediate resuscitation or very urgent vs. others). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated. All statistical analyses were conducted using R Studio 4.3.4.

- Results

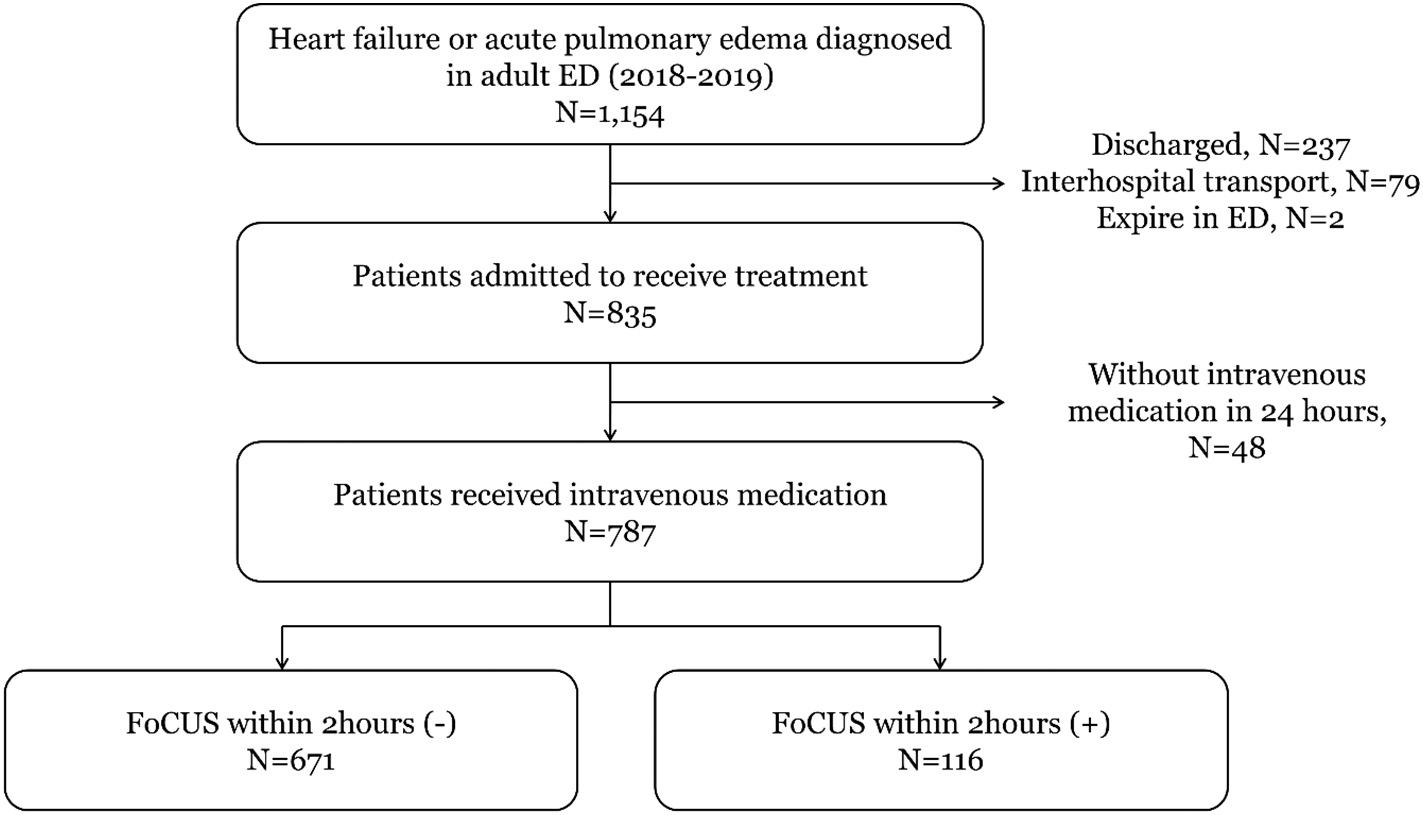

Between January 2018 and December 2019, 1154 patients with acute HF visited the ED. After excluding patients who were discharged from the ED (n = 237), transferred to another institution (n = 79), died in the ED (n = 2), and did not receive intravenous medication (n = 48), 787 patients were included in the final analysis. FoCUS was performed in 116 patients (Fig. 1). Table 1 describes the individual char- acteristics according to the FoCUS. The study group was less likely to use private ambulances or emergency medical services to visit the ED or undergo chest computed tomography. They also showed a relatively lower heart rate at triage, higher estimated glomerular filtration rate, and shorter length of stay in the ED but a higher proportion of ICU admissions.

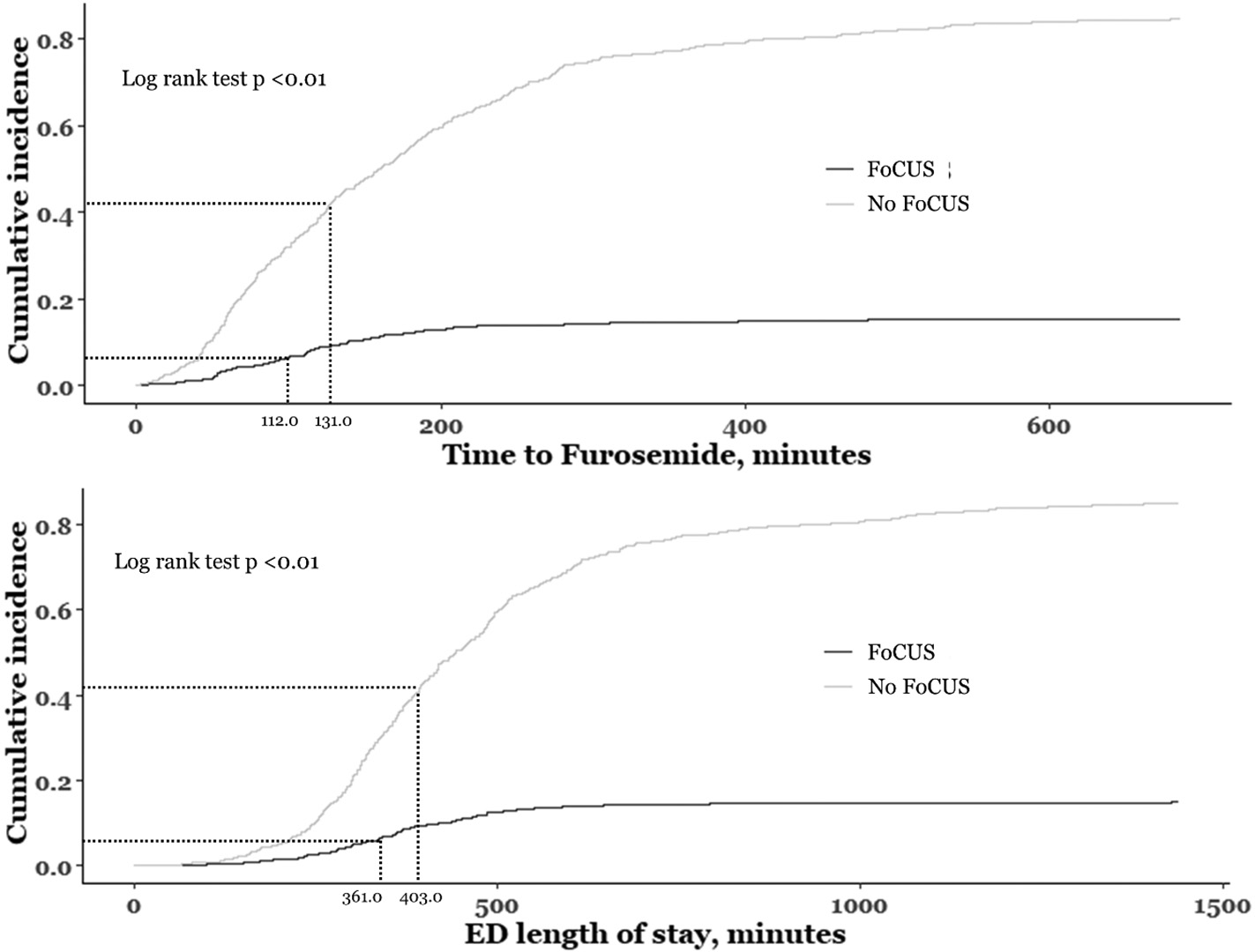

Compared to the non-FoCUS group, the FoCUS group showed a rela- tively shorter time to treatment and disposition. Among the treatment components, only furosemide showed a statistically significant differ- ence (Table 2). After adjusting for confounders, we found statistically significant differences for early furosemide and early IV medication ad- ministration in the FoCUS group compared to the non-FoCUS group; the adjusted ORs (95% CI) were 1.63 (1.04-2.55) for early diuretic adminis- tration and 1.88 (1.21-2.92) for early consultation for disposition (Table 3). The cumulative incidence plot for time to diuretic use and

ED, emergency department; FoCUS, focused cardiac ultrasound.

|

Table 1 Demographics and clinical findings by focused cardiac ultrasound. |

||||||

|

Total |

Non-FoCUS |

FoCUS |

||||

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

p-value |

|||

|

Total |

787 (100.0) |

671 (85.3) |

116 (14.7) |

|||

|

Age, mean (SD), years |

74.4 (12.0) |

74.6 (11.9) |

73.0 (12.7) |

0.198 |

||

|

Gender, Male |

385 (48.9) |

333 (49.6) |

52 (44.8) |

0.393 |

||

|

Chief complaint |

0.197 |

|||||

|

Chest pain |

76 (9.7) |

64 (9.5) |

12 (10.3) |

|||

|

Dyspnea |

601 (76.4) |

507 (75.6) |

94 (81.0) |

|||

|

Method of Entry |

0.008 |

|||||

|

Ambulance |

104 (13.2) |

96 (14.3) |

8 (6.9) |

|||

|

EMS |

205 (26.0) |

182 (27.1) |

23 (19.8) |

|||

|

Patient status at ED triage |

||||||

|

Altered mentality |

47 (6.0) |

40 (6.0) |

7 (6.0) |

1.000 |

||

|

Systolic BP, mmHg, median (q1-q3) |

145.0 (125.0-171.0) |

146.0 (127.0-171.0) |

136.0 (119.0-170.0) |

0.097 |

||

|

Diastolic BP, mmHg, median (q1-q3) |

81.0 (69.0-95.0) |

81.0 (69.0-95.0) |

78.0 (69.0-93.3) |

0.491 |

||

|

Heart rate, beats per min, median (q1-q3) |

88.0(72.0-107.0) |

90.0 (73.0-108.0) |

85.5 (68.8-104.3) |

0.038 |

||

|

Respiratory rate, per min, median (q1-q3) |

22.0 (18.0-24.0) |

22.0 (18.0-24.0) |

20.0 (18.0-24.0) |

0.419 |

||

|

Body temperature, Celsius, median (q1-q3) |

36.4 (36.2-36.7) |

36.5 (36.2-36.7) |

36.4 (36.2-36.6) |

0.458 |

||

|

Pulse oximeter, %, median (q1-q3) |

96.0 (94.0-98.0) |

96.0 (94.0-98.0) |

97.0 (94.0-98.0) |

0.442 |

||

|

ED triage result |

0.112 |

|||||

|

Immediate resuscitation |

54 (6.9) |

42 (6.3) |

12 (10.3) |

|||

|

Very urgent |

252 (32.0) |

224 (33.4) |

28 (24.1) |

|||

|

FOCUS findings |

||||||

|

Systolic dysfunction Mild |

– – |

27 (23.3) |

– |

|||

|

Severe |

– – |

45 (38.8) |

– |

|||

|

Pleural effusion or B-line of both lung |

– – |

25 (21.6) |

– |

|||

|

Plethora of inferior vena cava |

– – |

50 (43.1) |

– |

|||

|

Laboratory tests |

||||||

|

Hemoglobin, g/dl, median (q1-q3) |

11.2 (9.6-12.8) |

11.2 (9.6-12.8) |

11.3 (9.8-12.8) |

0.513 |

||

|

Estimated glomerular filtration rate, ml/min/1.73m2, median (q1-q3) |

45.0 (27.9-67.9) |

43.9 (27.5-65.5) |

52.6 (34.7-77.6) |

0.011 |

||

|

Serum Sodium, mmol/L, median (q1-q3) |

138.0 (135.0-141.0) |

138.0 (135.0-141.0) |

138.0 (136.0-140.0) |

0.681 |

||

|

High-sensitive troponin I, ng/ml, median (q1-q3) |

0.04 (0.02-0.10) |

0.04 (0.02-0.10) |

0.03 (0.02-0.11) |

0.494 |

||

|

Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/ml, median (q1-q3) |

0.952 |

|||||

|

400-3000 |

544 (73.4) |

467 (73.5) |

77 (72.6) |

|||

|

3000~ |

106 (14.3) |

91 (14.3) |

15 (14.2) |

|||

|

ED process |

||||||

|

Chest computed tomography |

220 (28.0) |

199 (29.7) |

21 (18.1) |

0.014 |

||

|

Echocardiography |

420 (53.4) |

352 (52.5) |

68 (58.6) |

0.260 |

||

|

Furosemide |

685 (87.0) |

583 (86.9) |

102 (87.9) |

0.873 |

||

|

634 (80.6) |

542 (80.8) |

92 (79.3) |

0.810 |

|||

|

Intravenous inotropics |

88 (11.2) |

76 (11.3) |

12 (10.3) |

0.881 |

||

|

Consult to cardiologist |

739 (93.9) |

630 (93.9) |

109 (94.0) |

1.000 |

||

|

Length of stay in ED, median (q1-q3) |

394.0 (301.0-532.0) |

403.0 (306.5-550.0) |

361.0 (292.3-466.0) |

0.003 |

||

|

ICU admission |

241.0 (30.6) |

194.0 (28.9) |

47.0 (40.5) |

0.017 |

||

FoCUS, Focused cardiac ultrasound; SD, standard deviation; EMS, emergency medical service; ED, emergency department; BP, blood pressure; ICU, intensive care unit.

Comparison of elapsed time interval from triage to treatment and disposition according to focused cardiac ultrasound.

|

FoCUS (-) |

FoCUS (+) |

FoCUS (-) |

FoCUS (+) |

|||||

|

Treatment components |

Mean(SD) |

Mean(SD) |

p-value |

Median (Q1-Q3) |

Median (Q1-Q3) |

p-value |

||

|

Time to diuretics, min (N = 646) |

176.8 (159.8) |

132.7 (99.3) |

0.009 |

131.0 (71.0-229.0) |

112.0 (65.0-163.0) |

0.021 |

||

|

Time to nitroglycerin, min (N = 599) |

192.5 (199.8) |

151.2 (156.6) |

0.065 |

144.0 (59.0-257.0) |

104.5 (56.5-187.5) |

0.066 |

||

|

Time to inotropics, min (N = 75) |

372.3 (334.0) |

260.9 (357.5) |

0.315 |

302.0 (159.8-390.0) |

150.0 (81.0-282.0) |

0.075 |

||

|

Time to any IV medications, min |

161.5 (158.5) |

116.3 (93.6) |

0.004 |

119.0 (58.0-210.0) |

93.0 (51.5-154.5) |

0.01 |

||

|

Time to disposition, min (N = 703) |

183.5 (127.5) |

148.3 (98.6) |

0.007 |

158.0 (121.0-215.0) |

132.5 (102.0-168.0) |

<0.001 |

FoCUS, focused cardiac ultrasound; SD, standard deviation; IV, intravenous.

Table 3

Multivariable logistic regression analysis according to focused cardiac ultrasound on out- comes.

IV medication was also higher in patients who underwent FoCUS. An early screening protocol by FoCUS in patients with presentations of acute HF could be helpful for optimizing ED practice.

Acute heart failure admitted through emergency department

IV diuretics within 2 h

|

Without FoCUS screening |

246/549 (44.8) |

1.00 |

|

FoCUS within 2 h |

56/97 (57.7) |

1.63 (1.04-2.55) |

|

Any IV medications within 2 h Without FoCUS screening |

305/606 (50.3) |

1.00 |

|

FoCUS within 2 h |

70/107 (65.4) |

1.88 (1.21-2.92) |

|

Consultation for disposition within 2 h |

||

|

Without FoCUS screening |

147/597 (24.6) |

1.00 |

|

FoCUS within 2 h |

37/106 (34.9) |

1.47 (0.93-2.32) |

Outcome, n/N (%)

Adjusted OR (95% CI)

Several studies have shown that point-of-care ultrasound narrows potential diagnosis, affects Diagnostic efficacy, and promotes better management in the ED [28-30]. Compared to comprehensive echocardi- ography, FoCUS consists of core components related to point-of-care management in EDs. This study aimed to clarify the systolic and Diastolic function of the heart, cardiomegaly, intravascular volume status, and probability of pulmonary edema. With the results from the FoCUS, emergency physicians may provide confidence in the acute manage- ment of HF.

In this study, no statistically significant difference was observed

OR, odd ratio; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; IV, intravenous.

Odd ratios were calculated adjusting for age group, gender, chief complaint, mode of en- trance, shock, desaturation, and severity by triage scale.

length of stay in the ED demonstrated steeper upward curves in the FoCUS group (Fig. 2).

- Discussion

We found a significant association between FoCUS and intrave- nous furosemide administration within 2 h in patients with acute HF admitted to the emergency department. Early administration of

for medications other than diuretics. According to the guidelines, acute HF with volume overload should be treated immediately with IV diuretics as part of the initial treatment [16]. In contrast, vasodilator therapy can be used as an adjunct in cases with insufficient response to diuretics. inotropic agents can be used as a temporizing measure in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and low cardiac output [31]. The administration of vasodilators or inotropic agents is usually determined on the basis of Hemodynamic responses and expert opinions. Likewise, the time to inotrope administration was longer than the time to disposition in our study.

In the FoCUS group, more patients underwent comprehensive echo- cardiography during the ED stay, even without statistical significance. A

Fig. 2. Density plot of time to diuretics by focused cardiac ultrasound. FoCUS, focused cardiac ultrasound; ED, emergency department.

recent study demonstrated that early FoCUS screening not only estab- lishes the diagnosis of acute HF but also identifies the underlying pathology [32]. We hypothesized that the need for Comprehensive echocardiography would decrease, but based on the FoCUS results, emergency physicians seemed to consider in-depth evaluations. In con- trast, the non-FoCUS group had a higher proportion of chest computed scans. It can be assumed that without FoCUS, physicians tend to access patients with classic clinical pathways consisting of laboratory tests, ra- diologic tests, and comprehensive echocardiography. Diuretic adminis- tration can be delayed using this approach.

Our study suggests that early screening using FoCUS may be asso- ciated with improved emergency care in patients with acute HF. Shortened Delays in diagnosis, treatment, and disposition can im- prove not only the patient’s clinical outcomes, but also the efficacy of medical resource use. As FoCUS should be performed by trained medical providers, effective protocols need to be developed and val- idated. A well-designed randomized controlled study should be per- formed to clarify the effects of FoCUS on physicians’ decision-making processes.

-

- Study limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, we enrolled patients who were diagnosed with acute HF or acute pulmonary edema in the ED, admitted to the hospital, and received intravenous medication. Pa- tients who were discharged from the ED were excluded because they were more likely to receive oral diuretics than IV diuretics. Al- though we specified the study population to clarify the association between time delay for IV medication and disposition, selection bias could have been affected. In addition, ED length of stay for pa- tients discharged from the ED may be associated with FoCUS evalua- tion, but this was not analyzed in our study. Second, FoCUS was defined as a Screening examination within 2 h of ED triage. The first examination was considered the optimal timing for emergency pa- tient screening. We assumed that ultrasound performed within 2 h could be considered an initial set of examinations since physicians usually do not have cardiac biomarkers or computed tomography re- sults. Third, owing to database limitations, the definite time of pa- tient assessment and Clinical decisions could not be discerned. We defined each point of clinical decision as the time of intravenous medication injection and consultation with the cardiologist, there- fore bias could have been introduced. Fourth, the severity of patients could affect the results, which we tried to adjust for multiple factors, including blood pressure, saturation, and triage level, but this may be insufficient. The FoCUS cohort showed a higher rate of ICU admission, suggesting that they are more likely to receive both FoCUS evaluation and earlier intervention. Fifth, the characteristics of each physician could affect the association, which cannot be easily quantified. Dur- ing the study period, > 50 emergency residents were on duty. The study hospital constructed its own practice protocol based on guide- lines, which may weaken individual variations in patient care. Sixth, we could not evaluate the directional relationship between FoCUS results and physician decisions in this database. Even the majority of FoCUS was conducted during ultrasound rotations by other resi- dents, and the result is assumed to affect the clinical decisions of on-duty residents, which is still a significant limitation. Finally, since this was an observational study in one institute, unmeasured bias could affect the results, therefore further investigation is needed for generalization.

FoCUS is significantly associated with the early administration of in- travenous furosemide in patients with acute HF admitted to the ED. Early FoCUS should be considered in patients with symptoms and signs of acute HF in the ED.

Disclaimer

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and its protocol was approved by the Seoul National University Hospital Institutional Review Board, which waived the requirement for informed consent (IRB No. 2012-134-1183).

Credit authorship contribution statement

Yun Ang Choi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jae Yun Jung: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Data curation. Joong Wan Park: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Inves- tigation, Data curation. Min Sung Lee: Writing – review & editing, Vali- dation, Methodology, Investigation. Tae Kwon Kim: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Stephen Gyung Won Lee: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Yong Hee Lee: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project adminis- tration, Investigation, Data curation. Ki Hong Kim: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No authors have other relationships, conditions, or circumstances that present potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

There is nothing to declare.

References

- Liao L, Allen LA, Whellan DJ. Economic burden of heart failure in the elderly. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(6):447-62.

- Cleland JG, Swedberg K, Follath F, Komajda M, Cohen-Solal A, Aguilar JC, et al. The EuroHeart Failure survey programme- a survey on the quality of care among pa- tients with heart failure in Europe. Part 1: patient characteristics and diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(5):442-63.

- Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12): 1123-33.

- DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2008;5:1-20.

- Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. Heart failure and the aging popu- lation: an increasing burden in the 21st century? Heart. 2003;89(1):49-53.

- Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(1):30-41.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-28.

- Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Greenberg BH, O’Connor CM, She L, et al. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in pa- tients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296(18):2217-26.

- Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, Dasgupta K, Butalia S, McBrien K, et al. Hyper- tension Canada’s 2018 Guidelines for Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(5): 506-25.

- Collins S, Storrow AB, Kirk JD, Pang PS, Diercks DB, Gheorghiade M. Beyond pulmo- nary edema: diagnostic, risk stratification, and treatment challenges of acute heart failure management in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(1): 45-57.

- Peacock WF, Emerman C, Costanzo MR, Diercks DB, Lopatin M, Fonarow GC. Early vasoactive drugs improve heart failure outcomes. Congest Heart Fail. 2009;15(6): 256-64.

- Maisel AS, Peacock WF, McMullin N, Jessie R, Fonarow GC, Wynne J, et al. Timing of immunoreactive B-type natriuretic peptide levels and treatment delay in acute de- compensated heart failure: an ADHERE (acute decompensated heart failure Na- tional Registry) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(7):534-40.

- Mebazaa A, Pang PS, Tavares M, Collins SP, Storrow AB, Laribi S, et al. The impact of early Standard therapy on dyspnoea in patients with acute heart failure: the URGENT-dyspnoea study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(7):832-41.

- Matsue Y, Damman K, Voors AA, Kagiyama N, Yamaguchi T, Kuroda S, et al. Time-to- furosemide treatment and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(25):3042-51.

- Metra M, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, et al. Effect of serelaxin on cardiac, renal, and hepatic biomarkers in the Relaxin in Acute Heart Failure (RELAX-AHF) development program: correlation with outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(2):196-206.

- Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Levy P, Ponikowski P, Peacock WF, Laribi S, et al. Recommen- dations on pre-hospital & early hospital management of acute heart failure: a con- sensus paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Aca- demic Emergency Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(6):544-58.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8): 891-975.

- Chavez MA, Shams N, Ellington LE, Naithani N, Gilman RH, Steinhoff MC, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Respir Res. 2014;15:50.

- Ding W, Shen Y, Yang J, He X, Zhang M. Diagnosis of pneumothorax by radiography and ultrasonography: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2011;140(4):859-66.

- Pomero F, Dentali F, Borretta V, Bonzini M, Melchio R, Douketis JD, et al. Accuracy of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography in the diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109 (1):137-45.

- Grimberg A, Shigueoka DC, Atallah AN, Ajzen S, Iared W. Diagnostic accuracy of so- nography for pleural effusion: systematic review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128(2): 90-5.

- Torres-Macho J, Anton-Santos JM, Garcia-Gutierrez I, de Castro-Garcia M, Gamez- Diez S, de la Torre PG, et al. initial accuracy of bedside ultrasound performed by emergency physicians for multiple indications after a short training period. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(9):1943-9.

- Riishede M, Lassen AT, Baatrup G, Pietersen PI, Jacobsen N, Jeschke KN, et al. Point- of-care ultrasound of the heart and lungs in patients with respiratory failure: a

pragmatic randomized controlled multicenter trial. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29(1):60.

- Neskovic AN, Hagendorff A, Lancellotti P, Guarracino F, Varga A, Cosyns B, et al. Emergency echocardiography: the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging recommendations. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):1-11.

- Neskovic AN, Edvardsen T, Galderisi M, Garbi M, Gullace G, Jurcut R, et al. Focus car- diac ultrasound: the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging viewpoint. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15(9):956-60.

- Kim KH, Jung JY, Park JW, Lee MS, Lee YH. Operating bedside cardiac ultrasound pro- gram in emergency medicine residency: A retrospective observation study from the perspective of performance improvement. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0248710.

- Kwon H, Kim YJ, Jo YH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim J, et al. The Korean triage and acuity scale: associations with admission, disposition, mortality and length of stay in the emer- gency department. International J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(6):449-55.

- Breitkreutz R, Price S, Steiger HV, Seeger FH, Ilper H, Ackermann H, et al. Focused echocardiographic evaluation in life support and peri-resuscitation of emergency patients: a prospective trial. Resuscitation. 2010;81(11):1527-33.

- Jones AE, Tayal VS, Sullivan DM, Kline JA. Randomized, controlled trial of immediate versus delayed goal-directed ultrasound to identify the cause of nontraumatic hypo- tension in emergency department patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1703-8.

- Weile J, Frederiksen CA, Laursen CB, Graumann O, Sloth E, Kirkegaard H. Point-of- care ultrasound induced Changes in management of unselected patients in the emergency department – a prospective single-blinded observational trial. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1):47.

- Writing Committee M, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey Jr DE, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240-327.

- Via G, Hussain A, Wells M, Reardon R, ElBarbary M, Noble VE, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for focused cardiac ultrasound. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(7):683. e1-e33.